Cimetidine

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

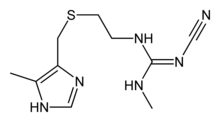

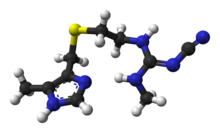

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 2-cyano- 1-methyl- 3-(2-[(5-methyl- 1H-imidazol- 4-yl)methylthio]ethyl)guanidine | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 51481-61-9 |

| ATC code | A02BA01 |

| PubChem | CID 2756 |

| IUPHAR ligand | 1231 |

| DrugBank | APRD00568 |

| ChemSpider | 2654 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C10H16N6S |

| Mol. mass | 252.34 g/mol |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–70% |

| Protein binding | 15–20% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Half-life | 2 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Licence data | US FDA:link |

| Pregnancy cat. | B1(AU) B(US) |

| Legal status | Prescription Only (S4) (AU) POM (UK) OTC/℞-only (U.S., depending on dosage strength) |

| Routes | Oral, parenteral |

| |

|

Cimetidine (INN) (pronounced /sɨˈmɛtɨdiːn/, /saɪˈmɛtɨdiːn/) is a histamine H2-receptor antagonist that inhibits the production of acid in the stomach. It is largely used in the treatment of heartburn and peptic ulcers. It is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline under the trade name Tagamet (sometimes Tagamet HB or Tagamet HB200). Cimetidine was approved in the UK in 1976 and was approved in the US by the Food & Drug Administration for prescriptions starting January 1, 1979.

Contents |

Clinical use

History and development

Cimetidine, approved by the FDA for inhibition of gastric acid secretion, has been advocated for a number of dermatological diseases. [1]Cimetidine was the prototypical histamine H2-receptor antagonist from which the later members of the class were developed. Cimetidine was the culmination of a project at Smith, Kline & French (SK&F; now GlaxoSmithKline) by James W. Black, C. Robin Ganellin, and others to develop a histamine receptor antagonist to suppress stomach acid secretion.[2] This was one of the first drugs discovered using a rational drug design approach, thanks to the efforts of medicinal chemists C. Robin Ganellin and Graham Durant and pharmacologist James Black at Smith, Kline, & French Laboratories (now GlaxoSmithKline; Sir James W. Black shared the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of propranolol and also is credited for the discovery of cimetidine; actually, the medicinal chemists would have made the discovery).[3]

At the time (1964) it was known that histamine could stimulate the secretion of stomach acid, but also that traditional antihistamines had no effect on acid production. In the process, the SK&F scientists also proved the existence of histamine H2-receptors.

The SK&F team used a rational drug-design structure starting from the structure of histamine - the only design lead, since nothing was known of the then hypothetical H2-receptor. Hundreds of modified compounds were synthesised in an effort to develop a model of the receptor. The first breakthrough was Nα-guanylhistamine, a partial H2-receptor antagonist. From this lead the receptor model was further refined and eventually led to the development of burimamide, the first H2-receptor antagonist. Burimamide, a specific competitive antagonist at the H2-receptor 100-times more potent than Nα-guanylhistamine, proved the existence of the H2-receptor.

Burimamide was still insufficiently potent for oral administration and further modification of the structure, based on modifying the pKa of the compound, lead to the development of metiamide. Metiamide was an effective agent, however it was associated with unacceptable nephrotoxicity and agranulocytosis[2]. It was proposed that the toxicity arose from the thiourea group, and similar guanidine-analogues were investigated until the ultimate discovery of cimetidine.

Cimetidine was first marketed in the United Kingdom in 1976; therefore, it took 12 years from initiation of the H2-receptor antagonist program to commercialization. The commercial name "Tagamet" was decided upon by fusing the two words"antagonist" and "cimetidine".[2] Subsequent to the introduction onto the U.S. drug market, two other H2-receptor antagonists were approved, ranitidine (Zantac, Glaxo Labs) and famotidine (Pepcid, Yamanouchi, Ltd.) Cimetidine became the first drug ever to reach more than $1 billion a year in sales, thus making it the first blockbuster drug.[4]

Other uses

In some studies, cimetidine has been found to reduce the debilitating pain and symptoms of herpes zoster, presumably by blocking the H2-receptors of T-lymphocyte suppressor cells.[5]

A number of "open label" studies showed that cimetidine was effective in the treatment of common warts, but more rigorous double-blinded clinical trials suggested it to be no more effective than a placebo. However, this study admits that their results may not be sound, due to small sample size, and did not explore higher dosing options.[6]

Another study by Yokoyama et al. used cimetidine for the treatment of chronic calcific tendinitis of the shoulder.[7] The small scale study took 16 individuals with calcific tendinitis in one shoulder, all of which had previously attempted other forms of therapy including steroid injection and arthroscopic lavage. During the course of the study 10 patients reported an elimination of pain and 9 displayed a complete disappearance of Calcium deposits. With results being on a small scale, it has been recommended that Cimetidine, for the treatment of chronic calcific tendinitis of the shoulder, be opened to large scale clinical trials.[8]

Cimetidine has been reported[9] for use in treatment of colorectal cancer - it is however not approved in the US by the FDA for cancer treatment.

In Asia, cimetidine, which molecularly targets EGF, VEGF and e-selectin associated with sialylated Lewis biomarkers and metastasis, has been combined with long term, continuous low dose 5FU[10] or metronomic tegafur-uracil chemotherapy for advanced epithelial cancers, with unusually long survival[11] including for stage III colorectal cancers,[12] as well as refractory and recurrent cancers.

Cimetidine has been reported for use as an analgesic in experimental treatments of interstitial cystitis.

Pretreatment with cimetidine improves the accuracy of measured creatinine clearance testing when using urine collection analysis.

Adverse effects and interactions

Cimetidine is a known inhibitor of many isozymes of the cytochrome P450 enzyme system[13] (specifically CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4). This inhibition forms the basis of the numerous drug interactions that occur between cimetidine and other drugs. For example, cimetidine may decrease metabolism of some drugs, such as those used in hormonal contraception. Cimetidine interferes with metabolism of the hormone estrogen, enhancing estrogen activity. In women, this can lead to galactorrhea, whereas in men, gynecomastia has been reported;[14] during postmarketing surveillance in the 1980s, cases of male sexual dysfunction were also reported.[15][16] Cimetidine also affects the metabolism of methadone, sometimes resulting in higher blood levels and a higher incidence of side effects, and may interact with the antimalarial medication hydroxychloroquine.[17]

The development of longer-acting H2-receptor antagonists with reduced adverse effects such as ranitidine proved to be the downfall of cimetidine and, though it is still used, it is no longer among the more widely used H2-receptor antagonists. Side effects can include dizziness, and more rarely, headache.

Following administration of cimetidine, the half-life and AUC of zomitriptan and its active metabolites were approximately doubled (see CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY). See complete drug interactions for Zomig (triptan succinate used for migraine relief) in package insert: http://www1.astrazeneca-us.com/pi/Zomig.pdf

References

- ↑ Scheinfeld N. Cimetidine: A review of the recent developments. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9(2):4.[PMID: 12639457]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Tagamet: A medicine that changed people's lives". American Chemical Society. 2004. http://acswebcontent.acs.org/landmarks/tagamet/tagamet.html. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ↑ Silverman, Richard A. (2004). The organic chemistry of drug design and drug action. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 159. ISBN 0-12-643732-7.

- ↑ Whitney, Jake (February 2006). "Pharmaceutical Sales 101: Me-Too Drugs". Guernica. http://www.guernicamag.com/features/111/me_too_drugs/. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Faloon, William; Kitchen, Kate (March 2001). "Tagemet to Treat Herpes and Shingles". Life Extension Magazine. http://www.lef.org/magazine/mag2001/mar2001_report_tagamet_1.html. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Fit KE, Williams PC (Jul 2007). "Use of histamine2-antagonists for the treatment of verruca vulgaris". Ann Pharmacother 41 (7): 1222–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1H616. PMID 17535844.

- ↑ Yokoyama M, Aono H, Takeda A, Morita K (2003). "Cimetidine for chronic calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder". Reg Anesth Pain Med 28 (3): 248–52. doi:10.1053/rapm.2003.50048. PMID 12772145.

- ↑ "Musculoskeletal Pain". http://www.pain.com/sections/categories_of_pain/Musculoskeletal/resources/library/abstract.cfm?ID=5248&next_page=1&startrec=1&RecordDisplays=20&Search_phrase=shoulder. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ↑ "Colorectal Cancer - Page 2 Of 3: Online References For Health Concerns". http://www.lef.org/protocols/cancer/colorectal_02.htm+. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ↑ S Matsumoto, Y Imaeda, S Umemoto, K Kobayashi, H Suzuki1 and T Okamoto S (21 January 2002). doi=doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600048 "Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells". British Journal of Cancer 86 (1): 161-167. http://www.nature.com/bjc/journal/v86/n2/abs/6600048a.html doi=doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600048.

- ↑ Matsumoto S, Hayashi A, Kobayashi K, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S (February 2004). Cimetidine blocking of E-selectin expression inhibits sialyl Lewis-X-positive cancer cells from adhering to vascular endothelium. http://www.cancerprev.org/Meetings/2004/Symposia/1094/138.

- ↑ Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, Kobayashi K, Okamoto T (january 2002). "Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells.". British Journal of Cancer 86 (6): 161–167. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600048. PMID 19671906. PMC 2848289. http://www.nature.com/bjc/journal/v86/n2/abs/6600048a.html.

- ↑ Levine M, Law EY, Bandiera SM, Chang TK, Bellward GD (Feb 1998). "In vivo cimetidine inhibits hepatic CYP2C6 and CYP2C11 but not CYP1A1 in adult male rats". The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 284 (2): 493–9. PMID 9454789. http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9454789.

- ↑ Michnovicz JJ, Galbraith RA (Feb 1991). "Cimetidine inhibits catechol estrogen metabolism in women". Metabolism: clinical and experimental 40 (2): 170–4. PMID 1988774.

- ↑ Sawyer D, Conner CS, Scalley R (February 1981). "Cimetidine: adverse reactions and acute toxicity". Am J Hosp Pharm 38 (2): 188–97. PMID 7011006.

- ↑ Sabesin SM (1993). "Safety issues relating to long-term treatment with histamine H2-receptor antagonists". Aliment Pharmacol Ther 7 Suppl 2: 35–40. PMID 8103374.

- ↑ Furst DE (June 1996). "Pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine during treatment of rheumatic diseases". Lupus 5 Suppl 1: S11–5. PMID 8803904.

External links

- Cimetidine as a Cause of Sexual Impotence - Cimetidine and Impotence

- American Chemical Society - National Historic Chemical Landmarks - Tagamet: A medicine that changed people's lives

- Tagamet HB200

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||