Flame

A flame (from Latin flamma) is the visible (light-emitting) gaseous part of a fire. It is caused by a highly exothermic reaction (for example, combustion, a self-sustaining oxidation reaction) taking place in a thin zone.[1] If a fire is hot enough to ionize the gaseous components, it can become a plasma.[2]

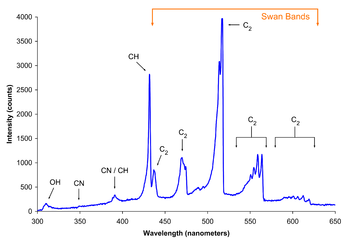

Color and temperature of a flame are dependent on the type of fuel involved in the combustion, as, for example, when a lighter is held to a candle. The applied heat causes the fuel molecules in the candle wick to vaporize. In this state they can then readily react with oxygen in the air, which gives off enough heat in the subsequent exothermic reaction to vaporize yet more fuel, thus sustaining a consistent flame. The high temperature of the flame tears apart the vaporized fuel molecules, forming various incomplete combustion products and free radicals, and these products then react with each other and with the oxidizer involved in the reaction. Sufficient energy in the flame will excite the electrons in some of the transient reaction intermediates such as CH and C2, which results in the emission of visible light as these substances release their excess energy (see spectrum below for an explanation of which specific radical species produce which specific colors). As the combustion temperature of a flame increases (if the flame contains small particles of unburnt carbon or other material), so does the average energy of the electromagnetic radiation given off by the flame (see blackbody).

Other oxidizers besides oxygen can be used to produce a flame. Hydrogen burning in chlorine produces a flame and in the process emits gaseous hydrogen chloride (HCl) as the combustion product.[3] Another of many possible chemical combinations is hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide which is hypergolic and commonly used in rocket engines. Fluoropolymers can be used to supply fluorine as an oxidizer of metallic fuels, e.g. in the magnesium/teflon/viton composition.

The chemical kinetics occurring in the flame are very complex and involves typically a large number of chemical reactions and intermediate species, most of them radicals. For instance, a well-known chemical kinetics scheme, GRI-Mech,[4] uses 53 species and 325 elementary reactions to describe combustion of biogas.

There are different methods of distributing the required components of combustion to a flame. In a diffusion flame, oxygen and fuel diffuse into each other; where they meet the flame occurs. In a premixed flame, the oxygen and fuel are premixed beforehand, which results in a different type of flame. Candle flames (a diffusion flame) operate through evaporation of the fuel which rises in a laminar flow of hot gas which then mixes with surrounding oxygen and combusts.

Contents |

Flame color

Flame color depends on several factors, the most important typically being blackbody radiation and spectral band emission, with both spectral line emission and spectral line absorption playing smaller roles. In the most common type of flame, hydrocarbon flames, the most important factor determining color is oxygen supply and the extent of fuel-oxygen pre-mixing, which determines the rate of combustion and thus the temperature and reaction paths, thereby producing different color hues.

In a laboratory under normal gravity conditions and with a closed oxygen valve, a Bunsen burner burns with yellow flame (also called a safety flame) at around 1,000 °C. This is due to incandescence of very fine soot particles that are produced in the flame. With increasing oxygen supply, less blackbody-radiating soot is produced due to a more complete combustion and the reaction creates enough energy to excite and ionize gas molecules in the flame, leading to a blue appearance. The spectrum of a premixed (complete combustion) butane flame on the right shows that the blue color arises specifically due to emission of excited molecular radicals in the flame, which emit most of their light well below ~565 nanometers in the blue and green regions of the visible spectrum.

Flame temperatures of common items include a blow torch - which can burn usually up to around 1,600 °C, a candle at 1,400 °C,[5] a propane torch at 1,995 °C, or a much hotter oxyacetylene combustion at 3,000 °C. Cyanogen produces an even hotter flame with a temperature of over 4,525 °C (8,177 °F) when it burns in oxygen.[6]

The colder part of a diffusion (incomplete combustion) flame will be red, transitioning to orange, yellow, and white the temperature increases as evidenced by changes in the blackbody radiation spectrum. For a given flame's region, the closer to white on this scale, the hotter that section of the flame is. The transitions are often apparent in fires, in which the color emitted closest to the fuel is white, with an orange section above it, and reddish flames the highest of all.[7] A blue-colored flame only emerges when the amount of soot decreases and the blue emissions from excited molecular radicals become dominant, though the blue can often be seen near the base of candles where airborne soot is less concentrated.[8]

Specific colors can be imparted to the flame by introduction of excitable species with bright emission spectrum lines. In analytical chemistry, this effect is used in flame tests to determine presence of some metal ions. In pyrotechnics, the pyrotechnic colorants are used to produce brightly colored fireworks.

Flame temperature

When looking at a flame's temperature there are many factors which can change or apply. One important one is that a flame's color does not necessarily determine a temperature comparison because black-body radiation is not the only thing that produces or determines the color seen; therefore it is only an estimation of temperature. Here are other factors that determine its temperature:

- Adiabatic flame; i.e., no loss of heat to the atmosphere (may differ in certain parts).

- Atmospheric pressure

- Percentage oxygen content of the atmosphere.

- The fuel being burned (i.e., depends on how quickly the process occurs; how violent the combustion is.)

- Any oxidation of the fuel.

- Temperature of atmosphere links to adiabatic flame temperature (i.e., heat will transfer to a cooler atmosphere more quickly).

- How stoichiometric the combustion process is (a 1:1 stoichiometricity) assuming no dissociation will have the highest flame temperature... excess air/oxygen will lower it and likewise not enough air/oxygen.

In fires (particularly house fires), the cooler flames are often red and produce the most smoke. Here the red color compared to typical yellow color of the flames suggests that the temperature is lower. This is because there is a lack of oxygen in the room and therefore there is incomplete combustion and the flame temperature is low, often just 600–850 °C. This means that a lot of carbon monoxide is formed (which is a flammable gas if hot enough) which is when in Fire and Arson investigation there is greatest risk of backdraft. When this occurs flames get oxygen, carbon monoxide combusts and temporary temperatures of up to 2000 °C occur. This is one of the most frightening things that firefighters encounter.

Common flame temperatures

This is a rough guide to flame temperatures for various common substances (in 20 °C air at 1 atm. pressure):

| Material burned | Flame temperature (°C) |

|---|---|

| Charcoal fire | 750–1,200 |

| Methane (natural gas) | 900–1,500 |

| Propane blowtorch | 1,200–1,700 |

| Candle flame | ~1,100 (majority), hot spots may be 1300–1400 |

| Magnesium | 1,900–2,300 |

| Hydrogen torch | Up to ~2,000 |

| Acetylene blowlamp/blowtorch | Up to ~2,300 |

| Oxyacetylene | Up to ~3,300 |

| Backdraft flame peak | 1,700–1,950 |

| Bunsen burner flame | 900–1,600 (depending on the air valve) |

| Material burned | Max. flame temperature (°C, in air, diffusion flame)[7] |

|---|---|

| Wood | 1027 |

| Gasoline | 1026 |

| Methanol | 1200 |

| Kerosene | 990 |

| Animal fat | 800–900 |

| Charcoal (forced draft) | 1390 |

Cool flames

At temperatures as low as 120 °C, fuel-air mixtures can react chemically and produce very weak flames called cool flames. The phenomenon was discovered by Humphry Davy in 1817. The process depends on a fine balance of temperature and concentration of the reacting mixture, and if conditions are right it can initiate without any external ignition source. Cyclical variations in the balance of chemicals, particularly of intermediate products in the reaction, give oscillations in the flame, with a typical temperature variation of about 100 K, or between "cool" and full ignition. Sometimes the variation can lead to explosion.[9][10]

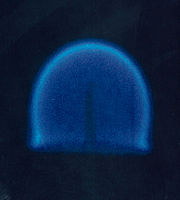

Flames in microgravity

In 2000, experiments by NASA confirmed that gravity plays an indirect role in flame formation and composition.[11] The common distribution of a flame under normal gravity conditions depends on convection, as soot tends to rise to the top of a flame (such as in a candle in normal gravity conditions), making it yellow. In microgravity or zero gravity environment, such as in orbit, natural convection no longer occurs and the flame becomes spherical, with a tendency to become bluer and more efficient. There are several possible explanations for this difference, of which the most likely is the hypothesis that the temperature is sufficiently evenly distributed that soot is not formed and complete combustion occurs.[12] Experiments by NASA reveal that diffusion flames in microgravity allow more soot to be completely oxidized after they are produced than do diffusion flames on Earth, because of a series of mechanisms that behave differently in microgravity when compared to normal gravity conditions.[13][14] These discoveries have potential applications in applied science and industry, especially concerning fuel efficiency.

References

- ↑ Law, C. K. (2006). "Laminar premixed flames". Combustion physics. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 300. ISBN 0521870526. http://books.google.com/?id=vWgJvKMXwQ8C&pg=RA300.

- ↑ Verheest, Frank (2000). "Plasmas as the fourth state of matter". Waves in Dusty Space Plasmas. Norwell MA: Kluwer Academic. p. 1. ISBN 0792362322. http://books.google.com/?id=LBpPMbADNCgC&pg=PA1.

- ↑ "Reaction of Chlorine with Hydrogen". http://genchem.chem.wisc.edu/demonstrations/Inorganic/pages/Group67/chlorine_and_hydrogen.htm.

- ↑ Gregory P. Smith et al.. "GRI-Mech 3.0". http://www.me.berkeley.edu/gri_mech/.

- ↑ Temperatures in flames and fires

- ↑ Thomas, N.; Gaydon, A. G.; Brewer, L., A. G.; Brewer, L. (1952). "Cyanogen Flames and the Dissociation Energy of N2". The Journal of Chemical Physics 20 (3): 369–374. doi:10.1063/1.1700426.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Christopher W. Schmidt, Steve A. Symes (2008). The analysis of burned human remains. Academic Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0123725100. http://books.google.com/?id=Q7Pb2wXV2woC&pg=PA4.

- ↑ Jozef Jarosinski, Bernard Veyssiere (2009). Combustion Phenomena: Selected Mechanisms of Flame Formation, Propagation and Extinction. CRC Press. p. 172. ISBN 0849384087. http://books.google.com/?id=hadB8msSl1EC&pg=PA172.

- ↑ Pearlman, Howard; Chapek, Richard M. (24 April 2000). "Cool Flames and Autoignition in Microgravity". NASA. http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/RT/RT1999/6000/6711wu.html. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ↑ Jones, John Clifford (September 2003). "Low temperature oxidation". Hydrocarbon process safety: a text for students and professionals. Tulsa, OK: PennWell. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9781593700041.

- ↑ Spiral flames in microgravity, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2000.

- ↑ CFM-1 experiment results, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, April 2005.

- ↑ LSP-1 experiment results, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, April 2005.

- ↑ SOFBAL-2 experiment results, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, April 2005.

See also

- Fire

- Plasma (physics)

- Pyranoscope