Grotesque

The word grotesque comes from the same Latin root as "Grotto", meaning a small cave or hollow. The original meaning was restricted to an extravagant style of Ancient Roman decorative art rediscovered and then copied in Rome at the end of the 15th century. The "caves" were in fact rooms and corridors of the Domus Aurea, the unfinished palace complex started by Nero after the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, which had become overgrown and buried, until they were broken into again, mostly from above.

In modern English, grotesque has come to be used as a general adjective for the strange, fantastic, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting, and thus is often used to describe weird shapes and distorted forms such as Halloween masks. In art, performance, and literature, grotesque, however, may also refer to something that simultaneously invokes in an audience a feeling of uncomfortable bizarreness as well as empathic pity. More specifically, the grotesque forms on Gothic buildings, when not used as drain-spouts, should not be called gargoyles, but rather referred to simply as grotesques, or chimeras.

Contents |

In art history

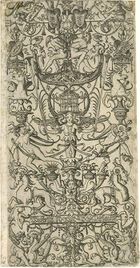

In art, grotesques are ornamental arrangements of arabesques with interlaced garlands and small and fantastic human and animal figures, usually set out in a symmetrical pattern around some form of architectural framework, though this may be very flimsy. Such designs were fashionable in ancient Rome, as fresco wall decoration, floor mosaics, etc., and were decried by Vitruvius (ca. 30 BCE), who in dismissing them as meaningless and illogical, offered quite a good description: "reeds are substituted for columns fluted appendages with curly leaves and volutes take the place of pediments, candelabra support representations of shrines, and on top of their roofs grow slender stalks and volutes with human figures senselessly seated upon them."

When Nero's Domus Aurea was inadvertently rediscovered in the late fifteenth century, buried in fifteen hundred years of fill, so that the rooms had the aspect of underground grottoes, the Roman wall decorations in fresco and delicate stucco were a revelation. The first appearance of the word grottesche appears in a contract of 1502 for the Piccolomini Library attached to the duomo of Siena. they were introduced by Raphael Sanzio and his team of decorative painters, who developed grottesche into a complete system of ornament in the Loggias that are part of the series of Raphael's Rooms in the Vatican Palace, Rome. "The decorations astonished and charmed a generation of artists that was familiar with the grammar of the classical orders but had not guessed till then that in their private houses the Romans had often disregarded those rules and had adopted instead a more fanciful and informal style that was all lightness, elegance and grace."[1] In these grotesque decorations a tablet or candelabrum might provide a focus; frames were extended into scrolls that formed part of the surrounding designs as a kind of scaffold, as Peter Ward-Jackson noted. Light scrolling grotesques could be ordered by confining them within the framing of a pilaster to give them more structure. Giovanni da Udine took up the theme of grotesques in decorating the Villa Madama, the most influential of the new Roman villas.

In the 16th century, such artistic license and irrationality was controversial matter. Francisco de Holanda puts a defense in the mouth of Michelangelo in his third dialogue of Da Pintura Antiga, 1548:

"this insatiable desire of man sometimes prefers to an ordinary building, with its pillars and doors, one falsely constructed in grotesque style, with pillars formed of children growing out of stalks of flowers, with architraves and cornices of branches of myrtle and doorways of reeds and other things, all seeming impossible and contrary to reason, yet yet it may be really great work if it is performed by a skillful artist."[2]

The delight of Mannerist artists and their patrons in arcane iconographic programs available only to the erudite could be embodied in schemes of grottesche,[3] Andrea Alciato's Emblemata (1522) offered ready-made iconographic shorthand for vignettes. More familiar material for grotesques could be drawn from Ovid's Metamorphoses.[4]

In Michelangelo's Medici Chapel Giovanni da Udine composed during 1532-33 "most beautiful sprays of foliage, rosettes and other ornaments in stucco and gold" in the coffers and "sprays of foliage, birds, masks and figures", with a result that did not please Pope Clement VII Medici, however, nor Giorgio Vasari, who whitewashed the grottesche decor in 1556.[5] Counter Reformation writers on the arts, notably Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, bishop of Bologna,[6] turned upon grottesche with a righteous vengeance.[7]

Giorgio Vasari recorded that Francesco Ubertini, called "Bacchiacca", delighted in inventing grotteschi, and (about 1545) painted for Duke Cosimo de' Medici a studiolo in a mezzanine at the Palazzo Vecchio "full of animals and rare plants".[8] Other 16th-century writers on grottesche included Daniele Barbaro, Pirro Ligorio and Gian Paolo Lomazzo.[9]

In the meantime, through the medium of engravings the grotesque mode of surface ornament passed into the European artistic repertory of the sixteenth century, from Spain to Poland. A classic suite was that attributed to Enea Vico, published in 1540-41 under an evocative explanatory title, Leviores et extemporaneae picturae quas grotteschas vulgo vocant, "Light and extemporaneous pictures that are vulgarly called grotesques". Later Mannerist versions, especially in engraving, tended to lose that initial ligtness and be much more densely filled than the airy well-spaced style used by the Romans and Raphael. Soon grottesche appeared in marquetry (fine woodwork), in maiolica produced above all at Urbino from the late 1520s, then in book illustration and in other decorative uses. At Fontainebleau Rosso Fiorentino and his team enriched the vocabulary of grotesques by combining them with the decorative form of strapwork, the portrayal of leather straps in plaster or wood moldings, which forms an element in grotesques.

Less used in the Baroque, the style was revived again in Neo-Classicism, when the lost spaciousness would be restored. Grotesque ornament received a further impetus from new discoveries of original Roman frescoes and stucchi at Pompeii and the other buried sites round Mount Vesuvius from the middle of the century. It continued in use, becoming increasingly heavy, in the Empire Style and then in the Victorian period, when designs often became as densely packed as in 16th century engravings, and the elegance and fancy of the style tended to be lost.

Extensions of the term in art

By extension backwards in time, in modern terminology for medieval illuminated manuscripts, drolleries, half-human thumbnail vignettes drawn in the margins, are also called "grotesques".

In contemporary illustration art, the "grotesque" figures, in the ordinary conversational sense, commonly appear in the genre grotesque art, also known as fantastic art.

A boom in the production of works of art in the grotesque genre, characterized the period 1920-1933 of German art.

In literature

In fiction, characters are usually considered grotesque if they induce both empathy and disgust. (A character who inspires disgust alone is simply a villain or a monster.) Obvious examples would include the physically deformed and the mentally deficient, but people with cringe-worthy social traits are also included. The reader becomes piqued by the grotesque's positive side, and continues reading to see if the character can conquer their darker side. In Shakespeare's The Tempest, the figure of Caliban has inspired more nuanced reactions than simple scorn and disgust.

Victor Hugo's Hunchback of Notre Dame is one of the most celebrated grotesques in literature. Dr. Frankenstein's monster can also be considered a grotesque, as well as the Phantom of the Opera and the Beast in Beauty and the Beast. Other instances of the romantic grotesque are also to be found in Edgar Allan Poe, E.T.A. Hoffmann, in Sturm und Drang literature or in Sterne's Tristram Shandy. Romantic grotesque is far more terrible and somber than medieval grotesque, which celebrated laughter and fertility.

The grotesque received a new shape with Alice in the Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, when a girl meets fantastic grotesque figures in her fantasy world. Carroll manages to make the figures seem less frightful and fit for children's literature, but still utterly strange.

Southern Gothic is a genre frequently identified with grotesques and William Faulkner is often cited as the ringmaster. Flannery O'Connor wrote, "Whenever I'm asked why Southern writers particularly have a penchant for writing about freaks, I say it is because we are still able to recognize one" ("Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction," 1960). In O'Connor's often-anthologized short-story "A Good Man Is Hard to Find," the Misfit, a serial killer, is clearly a maimed soul, utterly callous to human life but driven to seek the truth. The less obvious grotesque is the polite, doting grandmother who is unaware of her own astonishing selfishness. Another oft-cited example of the grotesque from O'Connor's work is her short-story entitled "A Temple Of The Holy Ghost." The American novelist, Raymond Kennedy is another author associated with the literary tradition of the grotesque.

The term Theatre of the Grotesque refers to an anti-naturalistic school of Italian dramatists, writing in the 1910s and 1920s, who are often seen as precursors of the Theatre of the Absurd.

In architecture

In architecture the term "grotesque" means a carved stone figure.

Grotesques are often confused with gargoyles, but the distinction is that gargoyles are figures that contain a water spout through the mouth, while grotesques do not. This type of sculpture is also called a chimera. Used correctly, the term gargoyle refers to mostly eerie figures carved specifically as terminations to spouts which convey water away from the sides of buildings. In the Middle Ages, the term babewyn was used to refer to both gargoyles and grotesques.[10] This word is derived from the Italian word babuino, which means "baboon".

In typography

The word "Grotesque", or "Grotesk" in German, is also frequently used as a synonym for sans-serif in typography. At other times, it is used (along with "Neo-Grotesque", "Humanist", "Lineal", and "Geometric") to describe a particular style or subset of sans-serif typefaces. The origin of this association can be traced back to English typefounder William Thorowgood, who first introduced the term "grotesque" and in 1835 produced 7-line pica grotesque—the first sans-serif typeface containing actual lowercase letters. An alternate etymology is possibly based on the original reaction of other typographers to such a strikingly featureless typeface.[11]

Popular Grotesque typefaces include Franklin Gothic, News Gothic, Haettenschweiler and Lucida Sans (although the latter lacks the spurred "G"), whereas popular Neo-Grotesque typefaces include Arial, Helvetica and Verdana.

See also

- Hunky Punk

- Mask

- Mummers' play

- Rigoletto, an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi.

- Sheela na Gig

- Southern Gothic

Notes

- ↑ Peter Ward-Jackson, "The Grotesque" in "Some main streams and tributaries in European ornament from 1500 to 1750: part 1" The Victoria and Albert Museum Bulletin (June 1967, pp 58-70) p 75.

- ↑ Quoted in David Summers, "Michelangelo on Architecture", The Art Bulletin 54.2 (June 1972:146-157) p. 151.

- ↑ An example, the vaulted arcade in the Palazzo del Governatore, Assisi, which was frescoed with grotesques in 1556, has been examined in the monograph by Ezio Genovesi, Le grottesche della 'Volta Pinta' in Assisi (Assisi, 1995): Genovesi explores the role of the local Accademia del Monte.

- ↑ Victor Kommerell, Metamorphosed Margins: The Case for a Visual Rhetoric of the Renaissance 'Grottesche' under the Influence of Ovid's Metamorphoses (Hildesheim, 2008)..

- ↑ "bellissimi fogliami, rosoni ed altri ornamenti di stuccho e d'oro" and "fogliami, uccelli, maschere e figure", quoted by Summers 1972:151 and note 30.

- ↑ Paleotti, Discorso intorno alle imagini sacre e profane (printed at Bologna, 1582)

- ↑ Noted by Summers 1972:152.

- ↑ "Dilettosi Bacchiacca di far grottesche; onde al Duca Cosimo fece uno studiuolo pieno d'animali e d'erbe rare ritratti dalle naturali che sono tenute bellissimi": quoted in Francesco Vossilla, "Cosimo I, lo scrittoio del Bachiacca, una carcassa di capodoglio e la filosofia naturale", Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, 37..2/3 (1993:381-395) p. 383; only fragments survive of the decor.

- ↑ All mentioned by Ezio Genovesi 1995, in providing explanation of the genre in the context of the painted vaulting at Assisi.

- ↑ Janetta Rebold Benton (1997). Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings. New York: Abbeville Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 0-7892-0182-8.

- ↑ "Linéale Grotesques". Rabbit Moon Press. 2009. http://typenstuff.com/help/4_22%20status%20books.pdf. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

Further reading

- Sheinberg, Esti (2000-12-29). Irony, satire, parody and the grotesque in the music of Shostakovich. UK: Ashgate. pp. 378. ISBN 0-7546-0226-5. http://www.dschjournal.com/journal15/books15.htm.

- Kayser, Wolfgang (1957) The grotesque in Art and Literature, New York, Columbia University Press

- Lee Byron Jennings (1963) The ludicrous demon: aspects of the grotesque in German post-Romantic prose, Berkeley, University of California Press

- Bakhtin, Mikhail (1941). Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Harpham, Geoffrey Galt (1982, 2006), On the Grotesque: Strategies of Contradiction in Art and Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

- Selected bibliography by Philip Thomson, The Grotesque, Methuen Critical Idiom Series, 1972.

- Dacos, N. La découverte de la Domus Aurea et la formation des grotesques à la Renaissance (London) 1969.

- Kort, Pamela (2004-10-30). Comic Grotesque: Wit And Mockery In German Art, 1870-1940. PRESTEL. pp. 208. ISBN 9783791331959. http://www.frontlist.com/detail/3791331957.

- FS Connelly "Modern art and the grotesque" 2003 assets.cambridge.org [1]

- Zamperini, Alessandra (2008). Ornament and the Grotesque: Fantastical Decoration from Antiquity to Art Nouveau. Thames and Hudson. pp. 320, 11" x 13", 250 color illustrations. ISBN 9780500238561. http://www.thamesandhudsonusa.com/new/fall08/523856.htm.

External links

- Video tour of the most vivid examples of medieval Parisian stone carving - the grotesques of Notre Dame

- The Grotesque: Bloom's Literary Themes edited by Harold Bloom and Blake Hobby

|

|||||||||||||||||