Khat

- For the headcloth worn by ancient Egyptian pharaohs see Khat (apparel); for the village in Azerbaijan see Hat, Azerbaijan; for the person see Anthony Mirra.

| Qat | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Catha edulis | |

| Conservation status | |

|

Least Concern (IUCN 2.3) |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Celastrales |

| Family: | Celastraceae |

| Genus: | Catha |

| Species: | C. edulis |

| Binomial name | |

| Catha edulis (Vahl) Forssk. ex Endl. |

|

Khat or qat (Catha edulis, family Celastraceae; pronounced /ˈkɑːt/, kaht; Arabic: قات /qaːt/; Ge'ez ጫት č̣āt; Somali: qaad) is a flowering plant native to tropical East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

Qat contains the alkaloid called cathinone, an amphetamine-like stimulant which is said to cause excitement, loss of appetite and euphoria. In 1980 the World Health Organization classified qat as a drug of abuse that can produce mild to moderate psychological dependence. The plant has been targeted by anti-drug organizations like the DEA.[1] It is a controlled or illegal substance in many countries, but is legal for sale and production in many others.

Contents |

Description

Qat is a slow-growing shrub or tree that grows to between 1.5 metres and 20 metres tall, depending on region and rainfall, with evergreen leaves 5–10 cm long and 1–4 cm broad. The flowers are produced on short axillary cymes 4–8 cm long, each flower small, with five white petals. The fruit is an oblong three-valved capsule containing 1–3 seeds.

History

Catha edulis appears to have originated in Ethiopia.[2] It now occurs in Arabia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, the Congo, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and South Africa.[3] Sir Richard Burton suggested that qat was introduced to the Yemen from Ethiopia in the 15th century,[4] although this probably occurred much earlier. The ancient Egyptians considered the qat plant a "divine food" which was capable of releasing humanity's divinity. The Egyptians used the plant for more than its stimulating effects; they used it as a metamorphic process and transcended into "apotheosis", intending to make the user god-like.[5]

The earliest known documented description of qat dates is found in the Kitab al-Saidana fi al-Tibb, an 11th century work on pharmacy and materia medica written by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, a Persian scientist and biologist. Unaware of its origins, al-Bīrūnī wrote that qat is:[6]

"a commodity from Turkestan. It is sour to taste and slenderly made in the manner of batan-alu. But qat is reddish with a slight blackish tinge. It is believed that batan-alu is red, coolant, relieves biliousness, and is a refrigerant for the stomach and the liver."

In 1854, the Malay writer Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir noted that the custom of chewing Khat was prevalent in Al Hudaydah in Yemen:

"I observed a new peculiarity in this city — everyone chewed leaves as goats chew the cud. There is a type of leaf, rather wide and about two fingers in length, which is widely sold, as people would consume these leaves just as they are; unlike betel leaves, which need certain condiments to go with them, these leaves were just stuffed fully into the mouth and munched. Thus when people gathered around, the remnants from these leaves would pile up in front of them. When they spat, their saliva was green. I then queried them on this matter: ‘What benefits are there to be gained from eating these leaves?’ To which they replied, ‘None whatsoever, it’s just another expense for us as we’ve grown accustomed to it’. Those who consume these leaves have to eat lots of ghee and honey, for they would fall ill otherwise. The leaves are known as Kad."[7]

Cultivation and uses

The qat plant is known by a variety of names, such as qat and gat in Yemen, qaat and jaad in Somalia, and chat in Ethiopia. It is also known as Jimma in the Oromo language and Miraa in the Meru Language. Qat has been grown for use as a stimulant for centuries in the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. There, chewing qat predates the use of coffee and is used in a similar social context.

Its fresh leaves and tops are chewed or, less frequently, dried and consumed as tea, in order to achieve a state of euphoria and stimulation; it also has anorectic side-effects. Due to the availability of rapid, inexpensive air transportation, the plant has been reported in England, Wales, Rome, Amsterdam, Canada, Australia, New Zealand[8] and the United States. The international community has become more aware of this plant through media reports pertaining to the United Nations mission in Somalia, where qat use is widespread, and its role in the Persian Gulf.

Qat use has traditionally been confined to the regions where qat is grown, because only the fresh leaves have the desired stimulating effects. In recent years improved roads, off-road motor vehicles and air transport have increased the global distribution of this perishable commodity. Traditionally, qat has been used as a socializing drug, and this is still very much the case in Yemen where qat chewing is predominantly, although not exclusively, a male habit.[9]

In other countries, qat is consumed largely by single individuals and at parties. It is mainly a recreational drug in the countries which grow qat, though it may also be used by farmers and laborers for reducing physical fatigue or hunger and by drivers and students for improving attention. Within the counter-culture segments of the Kenyan elite population, qat (referred to as veve or mirra) is used to counter the effects of a hangover or binge drinking, similar to the use of the coca leaf in South America. In Yemen, some women have their own saloons for the occasion, and participate in chewing qat with their husbands on weekends. In many places where it is grown, qat has become mainstream enough for many children to start chewing the plant before puberty.

Qat is so popular in Yemen that its cultivation consumes much of the country's agricultural resources. It is estimated that 40% of the country's water supply goes towards irrigating it,[10] with production increasing by about 10% to 15% every year. Water consumption is so high that groundwater levels in the Sanaa basin are diminishing; because of this, government officials have proposed relocating large portions of the population of Sanaa to the coast of the Red Sea.[9]

One reason for cultivating qat in Yemen so widely is the high income it provides for farmers. Some studies done in 2001 estimated that the income from cultivating qat was about 2.5 million Yemeni rials per hectare, while it was only 0.57 million rials per hectare if fruits were cultivated. This is a strong reason farmers prefer to cultivate qat over coffee and fruits. It is estimated that between 1970 and 2000, the area on which qat was cultivated grew from 8,000 hectares to 103,000 hectares.[11]

In Somalia, the Supreme Islamic Courts Council, which took control of much of the country in 2006, banned qat during Ramadan, sparking street protests in Kismayo. In November 2006, Kenya banned all flights to Somalia, citing security concerns, prompting protests by Kenyan qat growers. The Kenyan Member of Parliament from Ntonyiri, Meru North District stated that local land had been specialized in qat cultivation, that 20 tons worth $800,000 were shipped to Somalia daily and that a flight ban could devastate the local economy.[12] With the victory of the Provisional Government backed by Ethiopian forces in the end of December 2006, qat has returned to the streets of Mogadishu, though Kenyan traders have noted demand has not yet returned to pre-ban levels.[13]

Chemistry and pharmacology

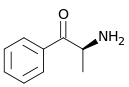

The stimulant effect of the plant was originally attributed to "katin", cathine, a phenethylamine-type substance isolated from the plant. However, the attribution was disputed by reports showing the plant extracts from fresh leaves contained another substance more behaviorally active than cathine. In 1975, the related alkaloid cathinone was isolated, and its absolute configuration was established in 1978. Cathinone is not very stable and breaks down to produce cathine and norephedrine. These chemicals belong to the PPA (phenylpropanolamine) family, a subset of the phenethylamines related to amphetamines and the catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine.[14]

Both of qat's major active ingredients – cathine and cathinone – are phenylalkylamines, meaning they are in the same class of chemicals as amphetamines. In fact, cathinone and cathine have a very similar molecular structure to amphetamine.[15]

When qat leaves dry, the more potent chemical, cathinone, decomposes within 48 hours leaving behind the milder chemical, cathine. Thus, harvesters transport qat by packaging the leaves and stems in plastic bags or wrapping them in banana leaves to preserve their moisture and keep the cathinone potent. It is also common for them to sprinkle the plant with water frequently or use refrigeration during transportation.

When the qat leaves are chewed, cathine and cathinone are released and absorbed through the mucous membranes of the mouth and the lining of the stomach. The action of cathine and cathinone on the reuptake of epinephrine and norepinephrine has been demonstrated in lab animals, showing that one or both of these chemicals cause the body to recycle these neurotransmitters more slowly, resulting in the wakefulness and insomnia associated with qat use.[16]

Receptors for serotonin show a high affinity for cathinone suggesting that this chemical is responsible for feelings of euphoria associated with chewing qat. In mice, cathinone produces the same types of nervous pacing or repetitive scratching behaviors associated with amphetamines.[17] The effects of cathinone peak after 15 to 30 minutes with nearly 98% of the substance metabolized into norephedrine by the liver.[15]

Cathine is somewhat less understood, being believed to act upon the adrenergic receptors causing the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine.[18] It has a half-life of about 3 hours in humans. Because the receptor effect are similar to those of cocaine medication, treatment of the occasional addiction is similar to that of cocaine. The medication bromocriptine can reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms within 24 hours.[19]

Growing

It takes nearly seven to eight years for the Qat plant to reach its full height. Other than access to sun and water, Qat requires little maintenance. Ground water is often pumped from deep wells by diesel engines to irrigate the crops, or brought in by water trucks. The plants are watered heavily starting around a month before they are harvested to make the leaves and stems soft and moist. A good Qat plant can be harvested four times a year, providing a year long source of income for the farmer.

Effects

.svg.png)

Qat consumption induces mild euphoria and excitement. A meta-analysis in The Lancet has stated that qat creates a pleasuring effect to the same degree as ecstasy. Individuals become very talkative under the influence of the drug and may appear to be unrealistic and emotionally unstable. The effects of oral administration of cathinone occur more rapidly than the effects of amphetamine, roughly 15 minutes as compared to 30 minutes in amphetamine. Qat can induce manic behaviors and hyperactivity.

The use of qat results in constipation. Dilated pupils (mydriasis), which are prominent during qat consumption, reflect the sympathomimetic effects of the drug, which are also reflected in increased heart rate and blood pressure. A state of drowsy hallucinations (hypnagogic hallucinations) may result coming down from qat use as well.

Withdrawal symptoms that may follow occasional use include mild depression and irritability. Withdrawal symptoms that may follow prolonged qat use include lethargy, mild depression, nightmares, and slight tremor. Qat is an effective anorectic (causes loss of appetite), so most of its users are underweight. Long-term use can precipitate the following effects: negative impact on liver function, permanent tooth darkening (of a greenish tinge), susceptibility to ulcers, and diminished sex drive.

Those who abuse the drug generally cannot stay without it for more than 4–5 days, without feeling tired and having difficulty concentrating. Some researchers also say that qat is “an amphetamine-like substance”, and those who use it are more likely to develop mental illnesses. Others say that these mental illnesses are the result of the financial problems and the sleeplessness that the drug causes. But it is still unclear if the consumption of qat directly affects the mental health of the user or not.[14] Occasionally a psychosis can result, resembling a hypomanic state in presentation.[21]

Demographics

It is estimated that several million people are frequent users of qat. Many of the users originate from countries between Sudan, Kenya and Madagascar and in the southwestern part of the Arabian Peninsula, especially Yemen. In Yemen, 80% of the males and 45% of the females were found to be qat users who had chewed daily for long periods of their life.

The traditional form of khat chewing in Yemen involves only male users; qat chewing by females is less formal and less frequent. In Saudi Arabia, the cultivation and consumption of qat are forbidden, and the ban is strictly enforced. The ban on qat is further supported by the clergy on the grounds that the Qur'an forbids anything that is harmful to the body. In Somalia, 61% of the population reported that they do use qat, 18% report habitual use, and 21% are occasional users.

Researchers estimate that about 70–80% of Yemenis between 16 and 50 years old chew qat, at least on occasion, and it has been estimated that Yemenis spend about 14.6 million person-hours per day chewing qat. The local researcher Ali Al-Zubaidi has estimated that the amount of money spent on qat has increased from 14.6 billion rials in 1990 to 41.2 billion rials in 1995. Researchers have also estimated that families spend about 17% of their income on qat.[11]

Research programs

The University of Minnesota recently launched an international program[22] focusing on health and brain effects of qat and led by professor Mustafa al'Absi. The Khat Research Program (KRP)[23] was funded by the National Institutes of Health of the United States. The inaugural event for the KRP was held in Sharm El-Sheik, Egypt, in December, 2009[24] in collaboration with the International Brain Research Organization (IBRO) and its local affiliates.

Health risks and benefits

Immediate effects:

- increased heart rate, breathing rate, body temperature, blood pressure

- increased alertness, excitement and energy

- decreased appetite.

Long-term effects:

- increases in severity of psychological problems (such as depression, anxiety, irritation and more severe psychological problems)

- difficulty sleeping

- impotence

- gastrointestinal tract problems, such as constipation

- inflammation of the mouth and other parts of the oral cavity

- oral cancer.[25][26]

Regulation

In 1965, the World Health Organization Expert Committee on Dependence-producing Drugs' Fourteenth Report noted, "The Committee was pleased to note the resolution of the Economic and Social Council with respect to qat, confirming the view that the abuse of this substance is a regional problem and may best be controlled at that level".[27] For this reason, qat was not Scheduled under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. In 1980 the World Health Organization classified qat as a drug of abuse that can produce mild to moderate psychological dependence.

Africa

Somalia

On 17 November 2006 the usage and distribution of qat was made illegal in Somalia.[28] The Supreme Islamic Courts Council, which took control of much of the country in that year, banned qat during Ramadan, sparking street protests in Kismayo. With the surprise victory of the Provisional Government backed by Ethiopian forces in the end of December 2006, qat has returned to the streets of Mogadishu.[13] Villagers and shop owners living on the coast of Somalia "make sure (that) pirates are well-stocked in qat".[29]

Europe

France

Qat is prohibited in France as a stimulant.[14]

Iceland

In August 2010 the Icelandic police intercepted qat smuggling for the first time. 37 kg were confiscated. The drugs were most likely intended for sale in Canada.[30]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands the active ingredients of qat, cathine and cathinone, are qualified as hard drugs and forbidden. The use of the unprocessed plant is legal and unrestricted. Use is mostly limited to the Somali community.[31] In 2008 health minister Ab Klink decided against qualifying the unprocessed plant as drugs after consultation with experts.[32] Khat is usually imported by airplane due to its quick decay.[33]

Norway

In Norway qat is classified as a narcotic drug and is illegal to use, sell and possess. Most users are Somali immigrants and qat is smuggled from the Netherlands and England.[34]

Norwegian Customs seized 3400 kilograms of qat in 2007, an increase from the 1900 kilograms in 2006.[35]

Poland

In Poland qat is classified as a narcotic drug and is illegal to use, sell and possess.[36]

United Kingdom

Although concerns have been expressed by commentators, health professionals and community members about the use of khat in the UK, particularly by immigrants from Somalia, Yemen and Ethiopia, it is not a currently a controlled substance.[37][38] As a result of these concerns, the Home Office commissioned successive research studies to look into the matter, and in 2005, presented the question of khat's legal status before the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. After a review of the evidence, the expert committee recommended in January 2006 that the status of khat as a legal substance should remain for the time being.[37]

In 2008, Conservative politician Sayeeda Warsi stated that a future Conservative government would ban khat.[39] The website of the Conservative Party, which is now the largest party in a coalition government in the UK, states that a Conservative government would "Tackle unacceptable cultural practices by", amongst other measures, "classifying Khat".[40] In 2009, the Home Office commissioned two new studies in the effects of khat use and in June 2010, a Home Office spokesperson stated: "The Government is committed to addressing any form of substance misuse and will keep the issue of khat use under close scrutiny".[41]

Because it is legal in the UK, and because of khat's short shelf life, Britain serves as a main gateway for khat being sent by air to North America.[42]

North America

Canada

In Canada, cathinone is a controlled substance under Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA), meaning it is illegal to possess or obtain unless approved by a medical practitioner. Punishment for the possession of khat could lead to a maximum sentence of three years in prison. The maximum punishment for trafficking or possession with the intent of trafficking is ten years in prison.[43][43]

In 2008, Canadian authorities reported that qat is the most common illegal drug being smuggled at airports.[44]

United States

In the United States, cathine is a Schedule IV controlled substance and cathinone is a Schedule I drug, according to the U.S. Controlled Substance Act. The 1993 DEA rule placing cathinone in Schedule I noted that it was effectively also banning qat.

Cathinone is the major psychoactive component of the plant Catha edulis (khat). The young leaves of qat are chewed for a stimulant effect. Enactment of this rule results in the placement of any material which contains cathinone into Schedule I.[45]

Qat has been seized by local police and federal authorities on several occasions.[46]

The plant itself is specifically banned in Missouri.

Khat, to include all parts of the plant presently classified botanically as catha edulis, whether growing or not; the seeds thereof; any extract from any part of such plant; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of the plant, its seed or extracts.[47]

Oceania

Australia

In Australia, the importation of qat is controlled under the Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulations 1956. Individual users must obtain permits from the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service and the Therapeutic Goods Administration to import up to 5 kg per month for personal use[48] Permits must also be endorsed by the Australian Customs Service which regulates the actual import of the drug.[49] In 2003, the total number of qat annual permits was 294 and the total number of individual qat permits was 202.

There are two types of import permits. The single use Permit to Import can be used only once and you must request a new permit for each time you wish to import qat. Annual Permits are labeled as such and consist of two pages. Annual Permits allow you to import up to 5 kg once a month for up to twelve months.

Qat is listed as a Schedule 2 dangerous drug in Queensland, in the same category as cannabis.[50] Legality in NSW is not clear.[51]

References

- ↑ DEA. ""2006 in Pictures"". http://www.dea.gov/slideshow/july2006.htm.

- ↑ CHEVALIER, A. (1949). "Les Cat's d'Arabie, d'Abyssinie et d'Afrique orientale". Revue de Botanique appliquée 29: 413.

- ↑ Upenn African_Studies (1 January 2010). ""Khat Information"". A1b2c3.com. http://www.a1b2c3.com/drugs/khat1.htm. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa.

- ↑ Giannini AJ, Burge H, Shaheen JM, Price WA (1986). "Khat: another drug of abuse?". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 18 (2): 155–8. PMID 3734955.

- ↑ Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè (2001). The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press. pp. 672–3. ISBN 0-521-40216-6. OCLC 174647831.

- ↑ Ché-Ross, Raimy (2000). "Munshi Abdullah's voyage to Mecca: A preliminary introduction and annotated translation". Indonesia and the Malay World 28: 173–213. doi:10.1080/713672763.

- ↑ New Zealand Herald: Concerns over African methamphetamine-like drug in Hamilton – 13 December 2006

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Yemen's qat habit soaks up water by Alex Kirby. Written 7 April 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ↑ "Sky News report on Yemen's Qat". News.sky.com. http://news.sky.com/skynews/Home/World-News/Yemen-Drug-Qat-Helping-Create-An-Environment-For-Extremism-In-The-Yemen/Article/201001315523792?lpos=World_News_First_World_News_Feature_Teaser_Region_0&lid=ARTICLE_15523792_Yemen:_Drug_Qat_Helping_Create_An_Environment_For_Extremism_In_The_Yemen. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Encyclopedia of Yemen (2nd ed), Alafif Cultural Foundation, pages 2309–2314, 2003.

- ↑ "Kenya bans all flights to Somalia", BBC News, 13 November 2006

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Somali Islamists are gone -- so "khat" is back! , Reuters, 2 January 2007

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Drugs.com (1 January 2007). "Complete Khat Info". http://www.drugs.com/npp/khat.html.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cox, G. (2003). "Adverse effects of khat: a review". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 9: 456–63. doi:10.1192/apt.9.6.456.

- ↑ Ahmed MB, el-Qirbi AB (August 1993). "Biochemical effects of Catha edulis, cathine and cathinone on adrenocortical functions". J Ethnopharmacol 39 (3): 213–6. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(93)90039-8. PMID 7903110.

- ↑ "Behavioral Effects of Cathinone". http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez.

- ↑ Adeoya-Osiguwa SA, Fraser LR (March 2007). "Cathine, an amphetamine-related compound, acts on mammalian spermatozoa via beta1- and alpha2A-adrenergic receptors in a capacitation state-dependent manner". Hum. Reprod. 22 (3): 756–65. doi:10.1093/humrep/del454. PMID 17158213.

- ↑ Giannini AJ, Miller NS, Turner CE (1992). "Treatment of khat addiction". J Subst Abuse Treat 9 (4): 379–82. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(92)90034-L. PMID 1362228.

- ↑ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- ↑ Giannini AJ, Castellani S (July 1982). "A manic-like psychosis due to khat (Catha edulis Forsk.)". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology 19 (5): 455–9. doi:10.3109/15563658208992500. PMID 7175990.

- ↑ "al'Absi Launches the Khat Research Program". Med.umn.edu. http://www.med.umn.edu/duluth/NewsReleases/2009/alAbsiKhatUse/home.html. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "KRP". Khatresearch.org. http://www.khatresearch.org. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ KRP Symposium

- ↑ "Khat - DrugInfo Clearinghouse". Druginfo.adf.org.au. 2006-09-20. http://www.druginfo.adf.org.au/druginfo/drugs/drugfacts/khat1.html#effects. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ "British-Yemeni Society: The impact of qat-chewing on health: a re-evaluation". Al-bab.com. http://www.al-bab.com/bys/articles/hassan05.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ UNODC

- ↑ "Africa | Somali Islamists ban popular drug". BBC News. 17 November 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6157216.stm. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "mbl.is 18/8/2010". 19.08.2010. http://www.mbl.is/mm/frettir/innlent/2010/08/18/hald_lagt_a_fikniefnid_khat_i_fyrsta_sinn/.

- ↑ "khat". Infopolitie.nl. http://www.infopolitie.nl/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1331:khat&catid=183:middelen&Itemid=46. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Qat niet verboden". DePers.nl. http://www.depers.nl/binnenland/163037/Qat-niet-verboden.html. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Overheid wil qat-importeur schadevergoeding betalen - Archief - de Volkskrant". Volkskrant.nl. http://www.volkskrant.nl/archief_gratis/article638486.ece/Overheid_wil_qat-importeur_schadevergoeding_betalen. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "NOVA paper 1/06". 16.03.07. http://www.nova.no/index.gan?objid=11648&subid=0&language=1.

- ↑ "Article from the Norwegian newspaper VG 20/02/07". 11.02.08. http://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/artikkel.php?artid=139097.

- ↑ "Dz.U. 2009 nr 63 poz. 520". http://isip.sejm.gov.pl/servlet/Search?todo=open&id=WDU20090630520.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Klein, Axel (2007). "Khat and the creation of tradition in the Somali diaspora". In Fountain, Jane; Korf, Dirk J.. Drugs in Society: European Perspectives. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 51–61. ISBN 9781846190933. http://www.radcliffe-oxford.com/books/samplechapter/0932/Chapt5-25459c40rdz.pdf.

- ↑ Warfa, Nasir; Klein, Axel; Bhui, Kamaldeep; Leavey, Gerard; Craig, Tom; Stansfeld, Stephen Alfred (2007). "Khat use and mental illness: A critical review". Social Science & Medicine 65 (2): 309–318. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.038. PMID 17544193.

- ↑ Warsi, Sayeeda (15 June 2008). "Conservatives will ban khat". Comment is free (The Guardian). http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2008/jun/15/drugspolicy.somalia. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "Where we stand: Community relations". Conservative Party. http://www.conservatives.com/Policy/Where_we_stand/Community_Relations.aspx. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "Call for new controls on legal drug khat". Sky News. 19 June 2010. http://news.sky.com/skynews/Home/UK-News/The-Legal-Drug-Khat-Is-Causing-Social-Problems-Among-The-East-African-Community-In-The-UK/Article/201006315650862?lpos=UK_News_Top_Stories_Header_2&lid=ARTICLE_15650862_The_Legal_Drug_Khat_Is_Causing_Social_Problems_Among_The_East_African_Community_In_The_UK. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "Toronto khat bust part of a growing trend, police say". CBC News. 26 January 2007. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/toronto/story/2007/01/26/tor-khat.html. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act". Laws.justice.gc.ca. 29 March 2010. http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/showdoc/cs/C-38.8/bo-ga:s_1::bo-ga:s_2?page=2. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "Gangs infiltrate Canada's airports / The Christian Science Monitor". CSMonitor.com. 16 December 2008. http://www.csmonitor.com/2008/1216/p06s01-wogn.html. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "Erowid Khat Vault : Law : Federal Register vol 58, no 9". Erowid.org. http://www.erowid.org/plants/khat/khat_law1.shtml. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Federal Register (14 January 1993). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Cathinone and 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine Into Schedule I". Erowid. http://articles.latimes.com/2006/aug/22/nation/na-khat22. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ "Section 195-017 Substances, how placed in schedules-li". Moga.mo.gov. 28 August 2009. http://www.moga.mo.gov/statutes/C100-199/1950000017.HTM. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, Cameron (23 July 2008). "Somali women demand government action on legal drug". The Australian (News Ltd). http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,24063019-5006785,00.html. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "Guidance for completing Licence and Import Permit applications (Khat)" (PDF). Department of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia. May 2008. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/79230B00D611D41FCA25744E00183283/$File/Guideline%20import%20Khat.pdf. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "Austlii Consolidated Acts – DRUGS MISUSE REGULATION 1987(Qld) – SCHEDULE 2". Austlii.edu.au. http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/legis/qld/consol_reg/dmr1987256/sch2.html?query=Catha%20edulis. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "Associate Professor Heather Douglas, University of Queensland". Law.uq.edu.au. 9 December 2009. http://www.law.uq.edu.au/index.html?page=122977. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

Bibliography

- Hilton-Taylor (1998). Catha edulis. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 12 May 2006.

- "Somali Islamists are gone – so "khat" is back!", Reuters, 2 January 2007

- Dale Pendell, Pharmakodynamis: Stimulating Plants, Potions and Herbcraft: Excitantia and Empathogenica, San Francisco: Mercury House, 2002.

External links

- The Gat Addiction in Israel Via Yemen

- BBC News: In pictures... growing khat

- Khat Research Program (KRP)

- Drugs.com, Complete Khat Information

- Esquire "High in Hell"

- Erowid: Khat Vault

- Growing Catha Edulis (Khat)

- BBC News: Getting to grips with khat in Somaliland

- BBC News: Harmless habit or dangerous drug?

- Ethiopian Plant Names

- Australian Government: Therapeutic Goods Administration Khat Importation Kit (archived)

- Star Tribune: Dozens Arrested Nationwide in Drug Case

- Qat news page – Alcohol and Drugs History Society (ADHS)

- Khat news page (ADHS)

- Seattle arrest – Khat and the Somalian community

- Village Voice article on khat

- Qat cultivation threatening water resources

- Qat, the Cursed Plant in Yemen :Part 1

- Qat, the Cursed Plant in Yemen :Part 2

- Qat, the Cursed Plant in Yemen :Part 3

- Qat, the Cursed Plant in Yemen :Part 4

- Qat, the Cursed Plant in Yemen :Part 5