Ligament

| Ligament |

|

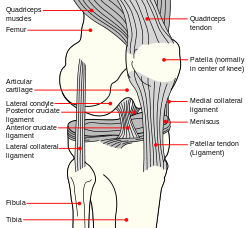

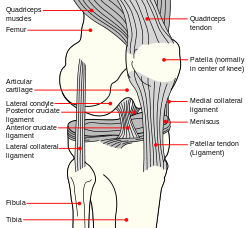

| Diagram of the right knee. |

|

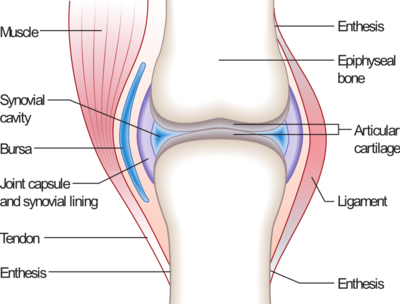

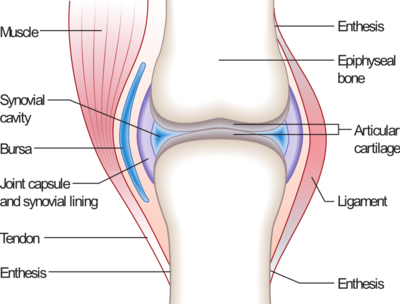

| Typical joint |

| Latin |

ligamenta |

In anatomy, the term ligament is used to denote three different types of structures:[1]

- Articular ligaments: Fibrous tissue that connects bones to other bones. They are sometimes called "articular larua"[2], "fibrous ligaments", or "true ligaments".

- Peritoneal ligaments: A fold of peritoneum or other membranes.

- Fetal remnant ligaments: The remnants of a tubular structure from the fetal period of life.

The first term is the one most commonly intended when using the word "ligament". This article briefly handles peritoneal and fetal remnant ligaments before focusing on articular legments.

The study of ligaments is known as desmology (from Greek δεσμός, desmos, "string"; and -λογία, -logia).

Peritoneal ligaments

Certain folds of peritoneum are referred to as ligaments.

Examples include:

- The hepatoduodenal ligament, that surrounds the hepatic portal vein and other vessels as they travel from the duodenum to the liver.

- The broad ligament of the uterus, also a fold of peritoneum.

Fetal remnant ligaments

Certain tubular structures from the fetal period are referred to as ligaments after they close up and turn into cord-like structures:

| Fetal |

Adult |

| ductus arteriosus |

ligamentum arteriosum |

| extra-hepatic portion of the fetal left umbilical vein |

ligamentum teres hepatis (the "round ligament of the liver"). |

| intra-hepatic portion of the fetal left umbilical vein (the ductus venosus) |

ligamentum venosum |

| distal portions of the fetal left and right umbilical arteries |

medial umbilical ligaments |

Articular ligaments

In its most common use, a ligament is a band of tough, fibrous dense regular connective tissue comprising attenuated collagenous fibers. Ligaments connect bones to other bones to form a joint. They do not connect muscles to bones; that is the job of tendons. Some ligaments limit the mobility of articulations, or prevent certain movements altogether.

Capsular ligaments are part of the articular capsule that surrounds synovial joints. They act as mechanical reinforcements. Extra-capsular ligaments join together and provide joint stability. Intra-capsular ligaments, which are much less common, also provide stability but permit a far larger range of motion. Cruciate ligaments occur in pairs.

Ligaments are elastic; they gradually lengthen when under tension, and return to their original shape when the tension is removed. This is in contrast with tendons, which are inelastic. However, ligaments can be plastic (i.e. retaining their changed shape) when stretched past a certain point or for a prolonged period of time. This is one reason why dislocated joints must be set as quickly as possible: if the ligaments lengthen too much, then the joint will be weakened, becoming prone to future dislocations. Athletes, gymnasts, dancers, and martial artists perform stretching exercises to lengthen their ligaments, making their joints more supple. The term double-jointed refers to people who have more elastic ligaments, allowing their joints to stretch and contort further. The medical term for describing such double-jointed persons is hyperlaxity and double-jointed is a synonym of hyperlax.

The consequence of a broken ligament can be instability of the joint. Not all broken ligaments need surgery, but if surgery is needed to stabilise the joint, the broken ligament can be repaired. Scar tissue may prevent this. If it is not possible to fix the broken ligament, other procedures such as the Brunelli Procedure can correct the instability. Instability of a joint can over time lead to wear of the cartilage and eventually to osteoarthritis.

Examples

Knee

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

- Lateral collateral ligament (LCL)

- Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL)

- Cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL) - quadruped equivalent of ACL

- Caudal cruciate ligament (CaCL) - quadruped equivalent of PCL

Head and neck

- Cricothyroid ligament

- Periodontal ligament

- Suspensory ligament of the lens

Pelvis

- Anterior sacroiliac ligament

- Posterior sacroiliac ligament

- Sacrotuberous ligament

- Sacrospinous ligament

- Inferior pubic ligament

- Superior pubic ligament

- Suspensory ligament of the penis

Thorax

- Suspensory ligament of the breast

Wrist

- Palmar radiocarpal ligament

- Dorsal radiocarpal ligament

- Ulnar collateral ligament

- Radial collateral ligament

See also

References

- ↑ ligament at eMedicine Dictionary

- ↑ ligament at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

External links

|

Joints (TA A03.0, GA 3.284) |

|

| Types |

fibrous: Gomphosis · Suture · Syndesmosis · Interosseous membrane

cartilaginous: Synchondrosis · Symphysis

synovial: Plane joint · 1° (Hinge joint, Pivot joint) · 2° (Condyloid joint, Saddle joint) · 3° (Ball and socket joint)

by range of motion: Synarthrosis · Amphiarthrosis · Diarthrosis

|

|

| Terminology |

Kinesiology · Anatomical terms of motion · Agonist/Antagonist

|

|

| Motions |

general: Flexion/Extension · Adduction/Abduction · Internal rotation/External rotation · Elevation/Depression

specialized/upper limbs: Protraction/Retraction · Supination/Pronation

specialized/lower limbs: Plantarflexion/Dorsiflexion · Eversion/Inversion

|

|

| Components |

capsular: Articular capsule (Synovial membrane, Fibrous membrane) · Synovial fluid · Synovial bursa · Articular disk/Meniscus

extracapsular: Ligament · Enthesis

|

|

|

|

|

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/, injr

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joints and ligaments of head and neck (TA A03.1.03-08, GA 3.287) |

|

| Temporomandibular |

capsule · articular disk

lateral (temporomandibular ligament) · medial (sphenomandibular ligament, stylomandibular ligament)

|

|

| Atlanto-occipital |

capsule · membranes (anterior atlantoöccipital membrane · posterior atlantoöccipital membrane)

|

|

|

|

|

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/, injr

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joints and ligaments of upper limbs (TA A03.5, GA 3.313) |

|

| Shoulder |

|

Sternoclavicular

|

Anterior sternoclavicular · Posterior sternoclavicular · Interclavicular · Costoclavicular

|

|

|

Acromioclavicular

|

Syndesmoses: Coracoacromial · Superior transverse scapular · Inferior transverse of scapula

Synovial: Acromioclavicular · Coracoclavicular (trapezoid, conoid)

|

|

|

Glenohumeral

|

Capsule · Coracohumeral · Glenohumeral (superior, middle, and inferior) · Transverse humeral · Glenoid labrum

|

|

|

| Elbow |

|

Humeroradial

|

Radial collateral

|

|

|

Humeroulnar

|

Ulnar collateral

|

|

|

Proximal radioulnar

|

Anular · Oblique cord

|

|

|

| Forearm |

|

Distal radioulnar

|

Palmar radioulnar · Dorsal radioulnar · Interosseous membrane of forearm

|

|

|

| Joints of hand |

|

|

Dorsal radiocarpal/Palmar radiocarpal · Dorsal ulnocarpal/Palmar ulnocarpal · Ulnar collateral/Radial collateral

|

|

|

Intercarpal, midcarpal

|

Radiate carpal · Dorsal intercarpal · Palmar intercarpal · Interosseous intercarpal · Scapholunate · Pisiform joint (Pisohamate, Pisometacarpal)

|

|

|

Carpometacarpal

|

Dorsal carpometacarpal · Palmar carpometacarpal · thumb: Radial collateral, Ulnar collateral

|

|

|

Intermetacarpal

|

Deep transverse metacarpal · Superficial transverse metacarpal

|

|

|

Metacarpophalangeal

|

Collateral · Palmar

|

|

|

Interphalangeal

|

Collateral · Palmar

|

|

|

Other

|

Carpal tunnel · Ulnar canal

|

|

|

|

|

|

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/, injr

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joints and ligaments of torso (TA A03.02-04, GA 3.299) |

|

| Vertebral |

|

Syndesmosis

|

|

Of vertebral bodies

|

anterior longitudinal ligament · posterior longitudinal ligament

|

|

|

Of vertebral arches

|

ligamenta flava · supraspinous ligament (nuchal ligament) · interspinal ligament · intertransverse ligament

|

|

|

|

Symphysis

|

intervertebral disc (annulus fibrosus, nucleus pulposus)

|

|

|

Synovial joint

|

|

Atlanto-axial

|

median: Cruciate ligament of atlas (Transverse ligament of atlas) · Alar ligament · Apical ligament of dens · Tectorial membrane of atlanto-axial joint

lateral: no ligaments

anterior atlantoaxial ligament · posterior atlantoaxial ligament

|

|

|

Zygapophysial

|

no ligaments

|

|

|

Lumbosacral

|

iliolumbar ligament

|

|

|

Sacrococcygeal

|

anterior sacrococcygeal ligament · posterior sacrococcygeal ligament

|

|

|

|

| Thorax |

|

Costovertebral

|

|

Head of rib

|

Radiate ligament · Intra-articular ligament

|

|

|

Costotransverse

|

Costotransverse ligament · Lumbocostal ligament

|

|

|

|

Sternocostal

|

interarticular sternocostal ligament · radiate sternocostal ligaments · costoxiphoid ligaments

|

|

|

Interchondral

|

no ligaments

|

|

|

Costochondral

|

no ligaments

|

|

|

| Pelvis |

|

|

Obturator membrane · Obturator canal

|

|

|

Pubic symphysis

|

superior pubic ligament · inferior pubic ligament

|

|

|

Sacroiliac

|

anterior sacroiliac ligament · posterior sacroiliac ligament · interosseous sacroiliac ligament

ligaments connecting the sacrum and ischium: sacrotuberous ligament · sacrospinous ligament

Greater sciatic foramen · Lesser sciatic foramen

|

|

|

|

|

|

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/, injr

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joints and ligaments of lower limbs (TA A03.6, GA 3.333) |

|

| Coxal/hip |

femoral (iliofemoral, pubofemoral, ischiofemoral) · head of femur · transverse acetabular · acetabular labrum · capsule · zona orbicularis

|

|

| Knee-joint |

|

|

Capsule · Anterior meniscofemoral ligament · Posterior meniscofemoral ligament

extracapsular: popliteal (oblique, arcuate) · collateral (medial/tibial, fibular/lateral)

intracapsular: cruciate ( anterior, posterior) · menisci (medial, lateral) · transverse

|

|

|

|

Patellar ligament · Infrapatellar fat pad

|

|

|

| Tibiofibular |

|

Superior tibiofibular

|

anterior of the head of the fibula · posterior of the head of the fibula

|

|

|

Inferior tibiofibular

|

Anterior tibiofibular · Posterior tibiofibular · Interosseous membrane of leg

|

|

|

| Joints of foot |

|

|

medial: medial of talocrural joint/deltoid (anterior tibiotalar, posterior tibiotalar, tibiocalcaneal, tibionavicular)

lateral: lateral collateral of ankle joint (anterior talofibular, posterior talofibular, calcaneofibular)

|

|

|

Subtalar/talocalcaneal

|

anterior/posterior · lateral/medial · interosseous

|

|

|

Transverse tarsal

|

|

Talocalcaneonavicular

|

dorsal talonavicular · plantar calcaneonavicular/spring · bifurcated (calcaneonavicular)

|

|

|

Calcaneocuboid

|

dorsal calcaneocuboid · long plantar · plantar calcaneocuboid · bifurcated (calcaneocuboid)

|

|

|

|

Distal intertarsal

|

|

Cuneonavicular

|

plantar · dorsal

|

|

|

Cuboideonavicular

|

plantar · dorsal

|

|

|

Intercuneiform

|

plantar · dorsal · interosseous

|

|

|

|

Other

|

|

Tarsometatarsal/Lisfranc

|

plantar · dorsal

|

|

|

Intermetatarsal/metatarsal

|

plantar · dorsal · interosseous · superficial transverse · deep transverse

|

|

|

Metatarsophalangeal

|

plantar · collateral

|

|

|

Interphalangeal

|

plantar · collateral

|

|

|

|

Arches

|

Longitudinal · Transverse

|

|

|

|

|

|

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/, injr

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominopelvic cavity: Abdomen/Abdominal cavity and Pelvis/Pelvic cavity and Peritoneal cavity (TA A10, GA 4.408 and GA 11.1147) |

|

| Extraperitoneal space |

Retroperitoneal space · Retropubic space

|

|

Peritoneal ligaments,

mesenteries, and folds |

|

Abdominal

|

|

From ventral mesentery

|

Lesser omentum: Hepatoduodenal ligament · Hepatogastric ligament

Liver: Coronary ligament (Left triangular ligament, Right triangular ligament, Hepatorenal ligament) · Falciform ligament (Round ligament of liver and Ligamentum venosum in it, but not of it)

|

|

|

From dorsal mesentery

|

Greater omentum: Gastrophrenic ligament · Gastrocolic ligament · Gastrosplenic ligament

Mesentery: Transverse mesocolon · Sigmoid mesocolon · Mesoappendix · Root of the mesentery

Splenorenal ligament · Phrenicocolic ligament

Folds: Umbilical folds (Supravesical fossa, Medial inguinal fossa, Lateral umbilical fold, Lateral inguinal fossa) · Ileocecal fold

|

|

|

Abdominal cavity

|

Greater sac · Omental bursa · Omental foramen

|

|

|

General

|

Cystohepatic triangle · Hepatorenal recess of subhepatic space · Abdominal wall (Inguinal triangle)

Peritoneal recesses: Paracolic gutters · Paramesenteric gutters

|

|

|

|

Urogenital peritoneum

|

|

|

Broad ligament of the uterus (Mesovarium, Mesosalpinx, Mesometrium) · Ovarian ligament · Suspensory ligament of the ovary

|

|

|

Recesses

|

♂: Recto-vesical pouch · Pararectal fossa

♀: Recto-uterine pouch · Recto-uterine fold (Uterosacral ligament) · Vesico-uterine pouch · Ovarian fossa · Paravesical fossa

|

|

|

|

|

Fetal vascular remnant ligaments (GA 6) |

|

| Heart |

Ligamentum arteriosum

|

|

| Liver |

Round ligament of liver · Ligamentum venosum

|

|

| Umbilical |

Medial umbilical ligament (see also Median umbilical ligament and Lateral umbilical fold)

|

|

|

Histology: connective tissue |

|

| Classification |

|

|

|

Loose

|

Areolar · Reticular

non-fibrous: Adipose (Brown, White)

|

|

|

Dense

|

Dense irregular connective tissue (Submucosa, Dermis) · Dense regular connective tissue (Ligament, Tendon, Aponeurosis) |

|

|

|

|

Mucous · Mesenchymal

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Composition |

|

|

|

Ground substance

|

Tissue fluid

|

|

|

|

Reticular fibers: Collagen

Elastic fibers: Fibrillin (FBN1, FBN2, FBN3)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resident

|

Fibroblast · Reticular cell · Tendon cell

Adipocyte

Chondroblast · Osteoblast

|

|

|

Wandering

cell

|

|

|

|

|

|

see also soft tissue

|

|

|

|

|

noco(i,,d,q,u,,p,,,v)/cong/tumr(n,e,d), sysi/

|

|

|

|

|

anat (h/n, u, t/d, a/p, l)/phys/hist

|

noco(m, s, c)/cong(d)/tumr, sysi/, injr

|

|

|

|

|

ligaments attach bone to bone