Myrrh

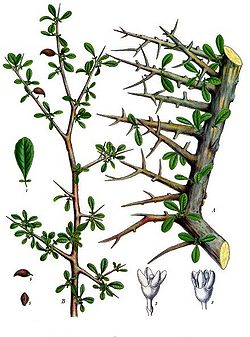

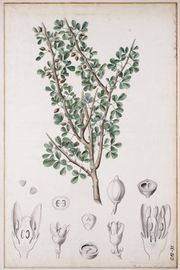

Myrrh is a reddish-brown resinous material collected from the dried sap of certain trees. The original myrrh species is Commiphora myrrha, which is native to Yemen, Somalia, and the eastern parts of Ethiopia. The related Commiphora gileadensis, native to Israel/Palestine and Jordan, is now accepted as an alternate source of myrrh.

Its name entered the English from the Greek myth of Myrrha; in the Greek language, the related word μύρον became a general term for perfume. However, the term ultimately derives from the Aramaic word ܡܪܝܪܐ (murr), meaning "bitter".

Since ancient times, myrrh has been valued for its fragrance and sometimes worth more than its weight in gold. It has been used throughout history for personal adornment and religious rituals.

Contents |

Characteristics

The scent of raw myrrh resin and its essential oil is sharp, pleasantly earthy, and somewhat bitter, with a "stereotypically resinous" character.

Myrrh resin can be qualitatively evaluated by its darkness and clarity, and especially the fragrance and stickiness of freshly broken pieces. It expands and "blooms" when heated or burned, instead of melting like most other aromatic resins. Its smoke is heavy, bitter and somewhat phenolic in scent, with a slight vanilla sweetness.

History

Myrrh has been traditionally used by many cultures as a perfume, incense, medication, or embalming ointment. In addition to its pleasant scent, it also has antimicrobial properties which have been investigated in recent times.

Classical antiquity

Myrrh originated from the Arabian Peninsula, where the gum resins were first collected. Its trade route reached Jerusalem and Egypt from modern Oman (then known as the Dhofar region) and Yemen, following the Red Sea coast of Arabia.

Herodotus wrote in the 5th century BC, "Arabia is the only country which produces myrrh, frankincense, cassia and cinnamon." Diodorus Siculus wrote in the second half of the first century BC that "all of Arabia exudes a most delicate fragrance; even the seamen passing by Arabia can smell the strong fragrance that gives health and vigor".

The Ancient Egyptians imported large amounts as far back as 3000 B.C. They used it to embalm the dead, as an antiseptic, and burned it for religious sacrifice. Archeologists have found at least two ostraca from Malkata (from New Kingdom Egypt, ca. 1390 to 1350 B.C.) that were lined with a shiny black or dark brown deposit that analysis showed to be chemically closest to myrrh.

In Ancient Rome, myrrh was priced at five times higher than frankincense. It was burned at ancient Roman funeral pyres to mask the reek of corpses; the Roman Emperor Nero supposedly burned a year's worth of myrrh at the funeral of his wife, Poppaea.

Pliny the Elder refers to myrrh as one of the ingredients of perfumes, and specifically as the "Royal Perfume" of the Parthians. He also mentions that myrrh was used to fumigate wine jars before bottling, and Fabius Dorsennus alludes to myrrh as a luxurious flavoring for wine.[1] It is still used to flavor the liqueur known as Fernet.

The myth of Myrrha

According to Greek and Roman classical mythology, Myrrha was a young Cypriot woman who was afflicted by the gods with an incestuous love of her father. Her old nurse helped her seduce him in darkness, and she fell pregnant. However, when her father learnt of her deception he was appalled and banished her. Taking pity on her, a god transformed her into a tree; hearing a child cry within the tree, some passersby delivered her baby Adonis, who was later the consort of Aphrodite. The sap from which myrrh is derived is said to be the tears of the transformed Myrrha. This story of myrrh's origin is preserved in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[2]

Judeo-Christian religious literature

In the Torah and the Old Testament, myrrh is a primary ingredient in the holy anointing oil that God commanded Moses to make:

Take also for yourself the finest of spices: of flowing myrrh five hundred shekels, ... You shall make of these... a holy anointing oil. With it you shall anoint the tent of meeting and the ark of the testimony... You shall anoint Aaron and his sons, and consecrate them, that they may minister as priests to Me.

Psalm 45 mentions myrrh as a kingly anointing oil, as part of a possible reference to the future Messiah:

In the New Testament, myrrh was one of the gifts of the Magi to the infant Jesus according to Matthew:

Then, opening their treasures, they offered him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh.

According to Mark, it was offered to Jesus as an intoxicant during the crucifixion:

And they brought him to the place called Gol'gotha (which means the place of a skull). And they offered him wine mingled with myrrh; but he did not take it.

John says it was used to prepare Jesus' body for burial:

Nicodemus, who had first come to Him by night, also came, bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about a hundred pounds weight. So they took the body of Jesus and bound it in linen wrappings with the spices, as is the burial custom of the Jews.

Current usage

Religious ritual

Because of its scriptural significance, myrrh is a common ingredient in incense offered during Christian liturgical celebrations (see Thurible).

In Roman Catholic liturgical tradition, pellets of myrrh are traditionally placed in the Paschal candle during the Easter Vigil. Eastern Christianity uses incense much more frequently, sometimes emphasizing its use at Vespers and Matins because of the Old Testament exhortation of the evening and morning offerings of incense.

Myrrh is also used to prepare the sacramental chrism used by many churches of both Eastern and Western rites. In the Middle East, the Eastern Orthodox Church traditionally uses myrrh-scented oil to perform the sacraments of chrismation and unction, both of which are commonly referred to as "receiving the Chrism".

Traditional medicine

In the Middle East myrrh has been used as a medical treatment for almost every human affliction. As of 2008, 35% of Saudi Arabians use myrrh as medicine.

Chinese medicine

In Chinese medicine, myrrh is classified as bitter and spicy, with a neutral temperature. It is said to have special efficacy on the heart, liver, and spleen meridians, as well as "blood-moving" powers to purge stagnant blood from the uterus. It is therefore recommended for rheumatic, arthritic, and circulatory problems, and for amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, menopause, and uterine tumors.

Its uses are similar to those of frankincense, with which it is often combined in decoctions, liniments, and incense. When used in concert, myrrh is "blood-moving" while frankincense moves the Qi, making it more useful for arthritic conditions.

It is combined with such herbs as notoginseng, safflower stamens, Angelica sinensis, cinnamon, and Salvia miltiorrhiza, usually in alcohol, and used both internally and externally.[3]

Ayurvedic medicine

Myrrh is used more frequently in Ayurveda and Unani medicine, which ascribe tonic and rejuvenative properties to the resin.

Myrrh (Daindhava) is used in many specially-processed rasayana formulas in Ayurveda. However, non-rasayana myrrh is contraindicated when kidney dysfunction or stomach pain are apparent, or for women who are pregnant or have excessive uterine bleeding.

A related species, called guggul in Ayurvedic medicine, is considered one of the best substances for the treatment of circulatory problems, nervous system disorders and rheumatic complaints.[4][5]

Modern medicine

In pharmacy, myrrh is used as an antiseptic in mouthwashes, gargles, and toothpastes[6] for prevention and treatment of gum disease.[7] Myrrh is currently used in some liniments and healing salves that may be applied to abrasions and other minor skin ailments. Myrrh has also been recommended as an analgesic for toothaches, and can be used in liniment for bruises, aches, and sprains.[8]

Scientific research

- In an attempt to determine the cause of its effectiveness, researchers examined the individual ingredients of an herbal formula used traditionally by Kuwaiti diabetics to lower blood glucose. Myrrh and aloe gums effectively improved glucose tolerance in both normal and diabetic rats.[9]

- Myrrh was shown[10] to produce analgesic effects on mice which were subjected to pain. Researchers at the University of Florence (Italy) showed that furanoeudesma-1,3-diene and another terpene in the myrrh affect opioid receptors in the mouse's brain which influence pain perception.

- Myrrh has been shown to lower Cholesterol LDL (bad cholesterol) levels as well as to increase the HDL (good cholesterol) in various tests on humans done in the past few decades. One recent (2009) documented laboratory test showed this same effect on albino rats.[11]

Other "myrrh" plants

The sap of a number of other Commiphora and Balsamodendron species is also known as myrrh, including that from Commiphora erythraea , Commiphora opobalsamum and Balsamodendron kua.

Fragrant "myrrh beads" are made from the crushed seeds of Detarium microcarpum, an unrelated West African tree. These beads are traditionally worn by married women in Mali as multiple strands around the hips.

The name "myrrh" is also applied to the potherb Myrrhis odorata otherwise known as "Cicely" or "Sweet Cicely".

See also

- Frankincense

- Chrism

- Naturalis Historia

- Pliny the Elder

References

- ↑ "Ancient Wine; The Search for the Origins of Viniculture" Patrick E. McGovern, 2003 ISBN 0-691-07080-6

- ↑ "Metamorphoses" 10.309-502, Ovid, trans. by David Raeburn, 2004 ISBN 0-140-44789-X

- ↑ Michael Tierra. "The Emmenagogues"

- ↑ Michael Moore Materia Medica

- ↑ Alan Tillotson "Myrrh"

- ↑ "Species Information". www.worldagroforestrycentre.org. http://www.worldagroforestrycentre.org/sea/products/afdbases/af/asp/SpeciesInfo.asp?SpID=17990. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ↑ Lawless, J. (2002) The Encyclopedia of Essential Oils, Harper Collins, p135

- ↑ "ICS-UNIDO - MAPs". www.ics.trieste.it. http://www.ics.trieste.it/MAPs/MedicinalPlants_Plant.aspx?id=599. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ Al-Awadi FM, Gumaa KA. Studies on the activity of individual plants of an antidiabetic plant mixture. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1987 Jan-Mar;24(1):37-41.

- ↑ Nature 1996, 379, 29

- ↑ Al-Amoudi, N. (2009). Hypocholesterolemic effect of some plants and their blend as studied on albino rats. International Journal of Food Safety, Nutrition and Public Health.

Further reading

- Massoud A, El Sisi S, Salama O, Massoud A (2001). "Preliminary study of therapeutic efficacy of a new fasciolicidal drug derived from Commiphora molmol (myrrh)". Am J Trop Med Hyg 65 (2): 96–99. PMID 11508399.

- Dalby, Andrew (2000). Dangerous Tastes: the story of spices. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0714127205 (US ISBN 0-520-22789-1), pp. 107–122.

- Dalby, Andrew (2003). Food in the ancient world from A to Z. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415232597, pp. 226–227, with additions

- Monfieur Pomet (1709). "Abyssine Myrrh)". History of Drugs. Abyssine Myrrh

- The One Earth Herbal Sourcebook: Everything You Need to Know About Chinese, Western, and Ayurvedic Herbal Treatments by Ph.D., A.H.G., D.Ay, Alan Keith Tillotson, O.M.D., L.Ac., Nai-shing Hu Tillotson, and M.D., Robert Abel Jr.

- Abdul-Ghani RA, Loutfy N, Hassan A. Myrrh and trematodoses in Egypt: An overview of safety, efficacy and effectiveness profiles. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:210-4( A good review on its antiparasitic activities) .

External links

- History of Myrrh and Frankincense (www.itmonline.org)

- Myrrh article by James A. Duke (www.herbcompanion.com)