Timbuktu

| Timbuktu Tombouctou |

|

|---|---|

| — City — | |

| transcription(s) | |

| - Koyra Chiini: | Tumbutu |

|

|

Timbuktu

|

|

| Coordinates: | |

| Country | |

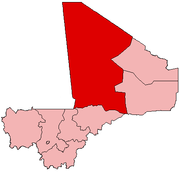

| Region | Tombouctou Region |

| Cercle | Timbuktu Cercle |

| Settled | 10th century |

| Elevation | 261 m (856 ft) |

| Population (2009)[1] | |

| - Total | 54,453 |

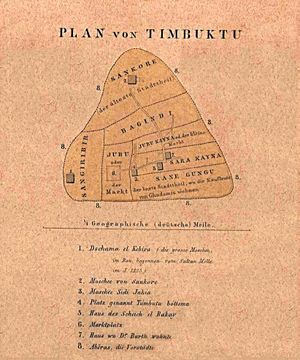

Timbuktu (Timbuctoo) (Koyra Chiini: Tumbutu; French: Tombouctou) is a city in Tombouctou Region, in the West African nation of Mali. It was made prosperous by the tenth mansa of the Mali Empire, Mansa Musa. It is home to Sankore University and other madrasas, and was an intellectual and spiritual capital and centre for the propagation of Islam throughout Africa in the 15th and 16th centuries. Its three great mosques, Djingareyber, Sankore and Sidi Yahya, recall Timbuktu's golden age. Although continuously restored, these monuments are today under threat from desertification.[2]

Populated by Songhay, Tuareg, Fulani, and Mandé people, Timbuktu is about 15 km north of the Niger River. It is also at the intersection of an east–west and a north–south Trans-Saharan trade route across the Sahara to Araouane. It was important historically (and still is today) as an entrepot for rock-salt originally from Taghaza, now from Taoudenni.

Its geographical setting made it a natural meeting point for nearby west African populations and nomadic Berber and Arab peoples from the north. Its long history as a trading outpost that linked west Africa with Berber, Arab, and Jewish traders throughout north Africa, and thereby indirectly with traders from Europe, has given it a fabled status, and in the West it was for long a metaphor for exotic, distant lands: "from here to Timbuktu."

Timbuktu's long-lasting contribution to Islamic and world civilization is scholarship. Timbuktu is assumed to have had one of the first universities in the world. Local scholars and collectors still boast an impressive collection of ancient Greek texts from that era.[3] By the 14th century, important books were written and copied in Timbuktu, establishing the city as the centre of a significant written tradition in Africa.[4]

Contents |

History

Origins

Timbuktu was established by the nomadic Tuareg as early as the 10th century. Although Tuaregs founded Timbuktu, it was only as a seasonal settlement. Roaming the desert during the wet months, in summer they stayed near the flood plains of the Inner Niger Delta. Since the terrain directly at the water wasn’t suitable due to mosquitoes, a well was dug a few miles from the river.[5][6]

Permanent Settlements

In the eleventh century merchants from Djenne set up the various markets and built permanent dwellings in the town, establishing the site as a meeting place for people traveling by camel. They also introduced Islam and reading, through the Qur'an. Before Islam, the population worshiped Ouagadou-Bida, a mythical water-serpent of the Niger River.[7] With the rise of the Ghana Empire, several Trans Saharan trade routes had been established. Salt from Mediterranean Africa was traded with West-African gold and ivory, and large numbers of slaves. Halfway through the eleventh century, however, new goldmines near Bure made for an eastward shift of the trade routes. This development made Timbuktu a prosperous city where goods from camels were loaded on boats on the Niger.

Rise of the Mali Empire

During the twelfth century, the remnants of the Ghana Empire were invaded by the Sosso Empire king Soumaoro Kanté.[9] Muslim scholars from Walata (beginning to replace Aoudaghost as trade route terminus) fled to Timbuktu and solidified the position of Islam. Timbuktu had become a center of Islamic learning, with its Sankore University and 180 Quranic schools.[5] In 1324 Timbuktu was peacefully annexed by king Musa I, returning from his pilgrimage to Mecca. The city now part of the Mali Empire, king Musa I ordered the construction of a royal palace and, together with his following of hundreds of Muslim scholars, built the learning center of Djingarey Ber in 1327.

By 1375, Timbuktu appeared in the Catalan Atlas, showing that it was, by then, a commercial center linked to the North-African cities and had caught Europe's eye.[10]

Tuareg Rule & the Songhayan Empire

With the power of the Mali Empire waning in the first half of the 15th century, Maghsharan Tuareg took control of the city in 1433-1434 and installed a Sanhaja governor.[11] Thirty years later however, the rising Songhay Empire expanded, absorbing Timbuktu in 1468-1469. Lead by consecutively Sunni Ali Ber (1468–1492), Sunni Baru (1492–1493) and Askia Mohammad I (1493–1528), who brought the Songhay Empire and Timbuktu a golden age. With the capital of the empire being Gao, Timbuktu enjoyed a relatively autonomous position. Merchants from Ghadames, Awjidah, and numerous other cities of North Africa gathered there to buy gold and slaves in exchange for the Saharan salt of Taghaza and for North African cloth and horses.[12] Leadership of the Empire stayed in the Askia dynasty until 1591, although internal fights led to a decline of prosperity in the city.

Moroccan Occupation

The city's capture on August 17, 1591 by an army sent by the Saadi ruler of Morocco, Ahmad I al-Mansur, and led by pasha Mahmud B. Zarqun in search of gold mines, brought the end of an era of relative autonomy. Intellectually, and to a large extent economically, Timbuktu now entered a long period of decline. In 1593, Saadi cited 'disloyalty' as the reason for arresting, and subsequently killing or exiling many of Timbuktu's scholars, including Ahmad Baba.[13] Perhaps the city's greatest scholar, he was forced to move to Marrakesh because of the intellectual oppostion to the city's Morrocan governor, where he continued to generate attention of the scholarly world.[14] Ahmad Baba later returned to Timbuktu, where he died in 1608. The ultimate decline continued, with the increasing trans-atlantic traderoutes (transporting African slaves, including leaders and scholars of Timbuktu) marginalising Timbuktu's role. While initially controlling the Morocco - Timbuktu traderoutes, the grip of the Moroccans on the city began losing its strength in the period until 1780, and in the early 19th century the Empire didn't succeed in protecting the city against invasions and the subsequent short occupations of the Tuareg (1800), Fula (1813) and Tukular 1840.[6][13] It is uncertain whether the Tukular were still in control,[15] or if the Tuaregs had once again regained power[16], when the French arrived.

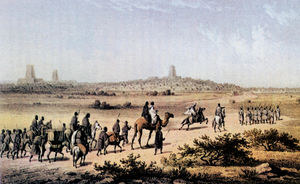

Discovery by the West

Historic descriptions of the city had been around since Leo Africanus' account in the first half of the 16th century, and they prompted several European individuals and organizations to make great efforts to discover Timbuktu and its fabled riches. In 1788 a group of titled Englishmen formed the African Association with the goal of finding the city and charting the course of the Niger River. The earliest of their sponsored explorers was a young Scottish adventurer named Mungo Park, who made two trips in search of the Niger River and Timbuktu (departing first in 1795 and then in 1805). It is believed that Park was the first Westerner to have reached the city, but he died in modern day Nigeria without having the chance to report his findings.[17] In 1824, the Paris-based Société de Géographie offered a 10,000 franc prize to the first non-Muslim to reach the town and return with information about it.[18] The Briton Gordon Laing arrived in August 1826 but was killed the following month by local Muslims who were fearful of European discovery and intervention.[19] The Frenchman René Caillié arrived in 1828 traveling alone disguised as a Muslim; he was able to safely return and claim the prize.[20]

Robert Adams, an African-American sailor, claimed to have visited the city in 1811 as a slave after his ship wrecked off the African coast.[21] He later gave an account to the British consul in Tangier, Morocco in 1813. He published his account in an 1816 book, The Narrative of Robert Adams, a Barbary Captive (still in print as of 2006), but doubts remain about his account.[22] Three other Europeans reached the city before 1890: Heinrich Barth in 1853 and the German Oskar Lenz with the Spaniard Cristobal Benítez in 1880.[23][24]

Part of the French Colonial Empire

After the scramble for Africa had been formalized in the Berlin Conference, land between the 14th meridian and Miltou, Chad would become French territory, bound in the south by a line running from Say, Niger to Baroua. Although the Timbuktu region was now French in name, the principle of effectivity needed France to actually hold power in those areas assigned, e.g. by signing agreements with local chiefs, setting up a government and making use of the area economically, before the claim would be definitive. On December 28, 1893, the city, by then long past its prime, was annexed by a small group of French, led by lieutenant Boiteux. Timbuktu was now part of French Sudan, a colony of France.[25][26] This situation lasted until 1902. After dividing part of the colony back in 1899, the remaining areas were now reorganized and, for a brief period, called Senegambia and Niger. Only two years later, in 1904, another reorganization followed and Timbuktu became part of Upper Senegal and Niger until, in 1920, the colony assumed its old name of French Sudan once again.[15]

World War II

During World War II, several legions were recruited in French Soudan, with some coming from Timbuktu, to help general Charles de Gaulle fight Nazi-occupied France and southern Vichy France.[17]

About 60 British merchant seamen from the SS Allende (Cardiff), sunk on the 17th March 1942 off the South coast of West Africa, were held prisoner in the city during the Second World War. Two months later, after having been transported from Freetown to Timbuktu, two of them, AB John Turnbull Graham (2 May 1942, age 23) and Chief Engineer William Soutter (28 May 1942, age 60) died there in May 1942. Both men were buried in the European cemetery - possibly the most remote British war graves tended by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.[27]

They were not the only war captives in Timbuktu: Peter de Neumann was one of 52 men imprisoned in Timbuktu in 1942 when their ship, the SS Criton, was intercepted by two Vichy French warships. Although several men, including de Neumann, escaped, they were all recaptured and stayed a total of ten months in the city, guarded by natives. Upon his return to England, he became known as "The Man from Timbuctoo".[28]

Independency & Onwards

After World War II had come to an end, the French government under Charles de Gaulle granted the colony more and more freedom. After a period as part of the short-lived Mali Federation, the Republic of Mali was proclaimed on September 22, 1960. After a November 19, 1968, a new constitution was created in 1974, making Mali a single-party state.[29] By then, the canal linking the city with the Niger River had already been filled with sand from the encroaching desert. Severe droughts hit the Sahel region in 1973 and 1985, decimating the Tuareg population around Timbuktu who relied on goat herding. The Niger's water level dropped, postponing the arrival of food transport and trading vessels. The crisis drove many of the inhabitants of Tombouctou Region to Algeria and Libya. Those who stayed relied on humanitarian organisations such as UNICEF for food and water.[30]

Etymology

Over the centuries, the spelling of Timbuktu has varied a great deal: from traveler Antonius Malfante’s “Thambet”, used in a letter he wrote in 1447 and also adopted by Ca Da Mosto in his “Voyages of Cadamosto, to Heinrich Barth’s Timbúktu and Timbu’ktu. As well as its spelling, Timbuktu’s etymology is still open to discussion.[25]

At least four possible origins of the name of Timbuktu have been described:

- Songhai origin: both Leo Africanus and Heinrich Barth believed the name was derived from two Songhau words. Leo Africanus argued: “This name [Timbuktu] was in our times (as some think) imposed upon this kingdom from the name of a certain town so called, which (they say) king Mense Suleiman founded in the yeere of the Hegeira 610 [1213-1214][31]."[32] The word itself consisted of two parts, tin (wall) and butu ("Wall of Butu"), the meaning of which Africanus did not explain. Heinrich Barth suggested: "the original form of the name was the Songhai form Túmbutu, from whence the Imóshagh made Tumbýtku, which was afterwards changed by the Arabs into Tombuktu” (1965[1857]: 284). On the meaning of the word Barth noted the following: “the town was probably so called, in the Songhai language: if it were a Temáshight word, it would be written Tinbuktu. The name is generally interpreted by Europeans [as] "well of Buktu", but "tin" has nothing to do with well”. (Barth 1965:284-285 footnote)

- Berber origin: Cissoko mentions a different etymology: the Tuareg founders of the city gave it a Berber name, a word composed of two parts: tim, the feminine form of In, meaning “place of”and “bouctou”, a contraction of the Arab word nekba (small dune). Hence, Timbuktu would mean “place covered by small dunes”.[33]

- Abd al-Sadi offers a third explanation in his Tarikh al-Sudan (ca. 1655): “in the beginning it was there that travelers arriving by land and water met. They made it the depot for their utensils and grain. Soon this place became a cross-roads of travelers who passed back and forth through it. They entrusted their property to a slave called Timbuctoo, [a] word that, in the language of those countries means the old”.

- The French orientalist René Basset forwarded another theory: the name derives from the Zenaga root b-k-t, meaning “to be distant” or “hidden”, and the feminine possessive particle tin. The meaning “hidden” could point to the city's location in a slight hollow.[10]

The validity of these theories depends on the identity of the original founders of the city: remnants dated from before the Songhay Empire exist and stories about earlier history point towards the Tuareg.[5][6] But, as recent as 2000, archeological research has not found remains dating from the 11th/12th century due to meters of sand that have buried the remains over the past centuries.[34] Without consensus, the etymology of Timbuktu remains unclear.

Legendary tales

Tales of Timbuktu's fabulous wealth helped prompt European exploration of the west coast of Africa. Among the most famous descriptions of Timbuktu are those of Ibn Battuta, Leo Africanus and Shabeni.

Ibn Battuta

The Malians fled in fear, and abandoned the city to them. The Mossi sultan entered Timbuktu, and sacked and burned it, killing many persons and looting it before returning to his land.

Among the earliest accounts of Timbuktu are those of famous traveller and scholar Ibn Battuta. Although Timbuktu was still part of the Mali Empire during the time of Ibn Battuta's visit to West Africa between February 1352 and December 1353, neighbouring states did pose a threat to the Empire, as did the increasing strength of the Songhay Empire that had been a vassal state so far. Already a commercial center by then, Timbuktu formed an attractive target for the Mossi Empire - situated in modern-day Burkina Faso - and it is their sacking of the city that Ibn Battuta describes:[10]

Leo Africanus

The rich king of Tombuto hath many plates and scepters of gold, some whereof weigh 1300 pounds. ... He hath always 3000 horsemen ... (and) a great store of doctors, judges, priests, and other learned men, that are bountifully maintained at the king's cost and charges.

The inhabitants are very rich, especially the strangers who have settled in the country [..] But salt is in very short supply because it is carried here from Tegaza, some 500 miles from Timbuktu. I happened to be in this city at a time when a load of salt sold for eighty ducats. The king has a rich treasure of coins and gold ingots.

Perhaps most famous among the accounts written about Timbuktu is that by Leo Africanus. Born El Hasan ben Muhammed el-Wazzan-ez-Zayyati in Granada in 1485, he was expelled along with his parents and thousands of other Muslims by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella after their reconquest of Spain in 1492. Settling in Morocco, he studied in Fes and accompanied his uncle on diplomatic missions throughout North Africa. During these travels, he visited Timbuktu. As a young man he was captured by pirates and presented as an exceptionally learned slave to Pope Leo X, who freed him, baptized him under the name “Johannis Leo de Medici,” and commissioned him to write, in Italian, a detailed survey of Africa. His accounts provided most of what Europeans knew about the continent for the next several centuries.[37] Describing Timbuktu when the Songhai empire was at its height, the English edition of his book includes the description:

According to Leo Africanus, there were abundant supplies of locally produced corn, cattle, milk and butter, though there were neither gardens nor orchards surrounding the city.[36] In another passage dedicated to describing the wealth of both the environment and the king, Africanus touches upon the rarity of some of Timbuktu's trade commodities: salt. These descriptions and passages alike caught the attention of European explorers. Africanus, though, also described the more mundane aspects of the city, such as the "cottages built of chalk, and covered with thatch" - although these went largely unheeded.[38]

Shabeni

The natives of the town of Timbuctoo may be computed at 40,000, exclusive of slaves and foreigners [..] The natives are all blacks: almost every stranger marries a female of the town, who are so beautiful that travellers often fall in love with them at first sight.

On the east side of the city of Timbuctoo, there is a large forest, in which are a great many elephants. Close to the town of Timbuctoo, on the south, is a small rivulet in which the inhabitants wash their clothes, and which is about two feet deep.

Roughly 250 years after Leo Africanus' visit to Timbuktu, the city had seen many rulers. The end of the 18th century saw the grip of the Moroccon rulers on the city wane, resulting in a period of unstable government by quickly changing tribes. During the rule of one of those tribes, the Hausa, a 14 year old child from Tetouan accompanied his father on a visit to Timbuktu. Growing up a merchant, he was captured and eventually brought to England.[39] Shabeni, or Asseed El Hage Abd Salam Shabeeny stayed in Timbuktu for three years before moving to Housa. Two years later, he returned to Timbuctoo to live there for another seven years - one of a population that was even centuries after its peak and excluding slaves, double the size of the 21st century town.

By the time Shabeni was 27, he was an established merchant in his hometown. Returning from a trademission to Hamburgh, his English ship was captured and brought to Ostende by a ship under Russian colours in December, 1789.

He was subsequently set free by the British consulate, but his ship set him ashore in Dover for fear of being captured again. Here, his story was recorded. Shabeeni gave an indication of the size of the city in the second half of the 18th. In an earlier passage, he described an environment quite different to nowadays Timbuktu's arid surroundings.

Centre of learning

"If the University of Sankore [...] had survived the ravages of foreign invasions, the academic and cultural history of Africa might have been different from what it is today."

| Timbuktu* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, v |

| Reference | 119 |

| Region** | Africa |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1988 (12th Session) |

| Endangered | 1990-2005 |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

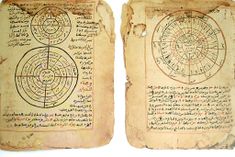

Timbuktu was a world center of Islamic learning from the 13th to the 17th century. The Malian government and NGOs have been working to catalog and restore the remnants of this scholarly legacy: Timbuktu’s manuscripts.[41]

Timbuktu’s rapid economic growth in the 13th and 14th centuries drew many scholars from nearby Walata,[40] leading up to the city’s golden age in the 15th and 16th centuries that proved fertile ground for scholarship of religions, arts and science. An active trade in books between Timbuktu and other parts of the Islamic world and emperor Askia Mohammed’s strong support led to the writing of thousands of manuscripts.[42]

Knowledge though, was not gathered through a European Medieval university model.[40] Lecturing was presented through a range of informal institutions called madrasahs.[43] Nowadays dubbed the ‘University of Timbuktu’, three madrasahs facilitated 25,000 students: Djinguereber, Sidi Yahya and Sankore.[44] These institutions were explicitly religious, as opposed to the more secular curricula of European universities. Moreover, where universities in the European sense started as corporations of students and teachers, West-African education was patronized by families or lineages, with the Aqit and Bunu al-Qadi al-Hajj families being two of the most prominent in Timbuktu. Although the basis of Islamic law and its teaching were brought to Timbuktu from North Africa with the spread of Islam, Western African scholarship developed: Ahmed Baba al Massufi is regarded as the city's greatest scholar.[14] Over time however, the share of patrons that originated from or identified themselves as West-Africans decreased.

Timbuktu served in this process as a distribution center of scholars and scholarship. Its reliance on trade meant intensive movement of scholars between the city and its extensive network of trade partners. In 1468-1469 though, many scholars left for Walata when Sunni Ali’s Songhay Empire absorbed Timbuktu and again in 1591 with the Moroccan occupation.[40]

This system of education survived until late 19th century, while the 18th century saw the institution of itinerant Quranic school as a form of universal education, where scholars would travel throughout the region with their students, begging for food part of the day.[41] Islamic education came under pressure after the French occupation, droughts in the 70s and 80s and by Mali’s civil war in the early 90s.[41]

The manuscripts and libraries of Timbuktu

Hundreds of thousands of manuscripts were collected in Timbuktu over the course of centuries: some were written in the town itself, others - including exclusive copies of the Qur’an for wealthy families- imported through the lively booktrade.

Hidden in cellars or buried, hid between the mosque's mud walls and safeguarded by their patrons, many of these manuscripts survived the city's decline. They now form the collection of several libraries in Timbuktu, holding up to 700,000 manuscripts:[45]

- Ahmed Baba Institute

- Mamma Haidara Library

- Fondo Kati

- Al-Wangari Library

- Mohamed Tahar Library

- Maigala Library

- Boularaf Collection

- Al Kounti Collections

These libraries are the largest among up to 60 private or public libraries that are estimated to exist in Timbuktu today: although some comprise little more than a row of books on a shelve or a bookchest.[46] Under these circumstances, the manuscripts are vulnerable to insect damage and theft, as well as long term climate damage, despite Timbuktu's arid climate. Started in 2008 as a part of UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme and a NEPAD Cultural Project, the Timbuktu Manuscripts Project aims to catelogize and preserve the works.[47]

Timbuktu today

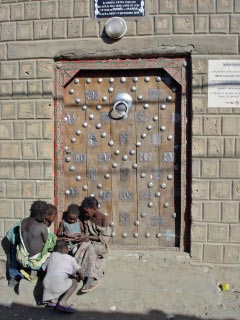

Today, Timbuktu is an impoverished town, although its reputation makes it a tourist attraction to the point where it even has an international airport (Timbuktu Airport). It is one of the eight regions of Mali, and is home to the region's local governor. It is the sister city to Djenné, also in Mali. The 1998 census listed its population at 31,973, up from 31,962 in the census of 1987.[48]

Timbuktu is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, listed since 1988. In 1990, it was added to the list of World Heritage Sites in danger due to the threat of desert sands. A program was set up to preserve the site and, in 2005, it was taken off the list of endangered sites. However, new constructions are threatening the ancient mosques, a UNESCO Committee warns.[49]

Timbuktu was one of the major stops during Henry Louis Gates' PBS special "Wonders of the African World". Gates visited with Abdel Kadir Haidara, curator of the Mamma Haidara Library together with Ali Ould Sidi from the Cultural Mission of Mali. It is thanks to Gates that an Andrew Mellon Foundation grant was obtained to finance the construction of the library's facilities, later inspiring the work of the Timbuktu Manuscripts Project. Unfortunately, no practising book artists exist in Timbuktu although cultural memory of book artisans is still alive, catering to the tourist trade. The town is home to an institute dedicated to preserving historic documents from the region, in addition to two small museums (one of them the house in which the great German explorer Heinrich Barth spent six months in 1853-54), and the symbolic Flame of Peace monument commemorating the reconciliation between the Tuareg and the government of Mali.

Attractions

Timbuktu's vernacular architecture is marked by mud mosques, which are said to have inspired Antoni Gaudí. These include

- Djinguereber Mosque, built in 1327 by El Saheli[50]

- Sankore Mosque, also known as Sankore University, built in the early fifteenth century

- Sidi Yahya mosque, built in the 1441 by Mohamed Naddah.

Other attractions include a museum, terraced gardens and a water tower.

Language

The main language of Timbuktu is a Songhay language called Koyra Chiini, spoken by over 80% of residents. Smaller groups, numbering 10% each before many were expelled during the Tuareg/Arab rebellion of 1990-1994, speak Hassaniya Arabic and Tamashek.

Climate

The weather is hot and dry throughout much of the year with plenty of sunshine. Average daily maximum temperatures in the hottest months of the year - May and June - exceed 40°C. Temperatures are slightly cooler, though still very hot, from July through September, when practically all of the meager annual rainfall occurs. Only the winter months of December and January have average daily maximum temperatures below 32°C.

| Climate data for Timbuktu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86) |

33.2 (91.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

40.0 (104) |

42.2 (108) |

41.6 (106.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

39.1 (102.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

36.8 (98.24) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

25.8 (78.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

20.98 (69.77) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 0.6 (0.024) |

0.1 (0.004) |

0.1 (0.004) |

1.0 (0.039) |

4.0 (0.157) |

16.4 (0.646) |

53.5 (2.106) |

73.6 (2.898) |

29.4 (1.157) |

3.8 (0.15) |

0.1 (0.004) |

0.2 (0.008) |

182.8 (7.197) |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization [51] | |||||||||||||

In popular culture

The image of the city as mysterious or mythical has survived to the present day in other countries: a survey among 150 young Britons in 2006 found 34% did not believe the town existed, while the other 66% considered it "a mythical place".[52]

Canadian rapper Tim Wallace, who hails from London, Ontario, chose the stage name "Timbuktu" as a play on his given name. Sometimes his name is shortened to "Buktu" or "Timmy Two-Titties," or even "Timberley Timberwolves."[53]

A 1959 film Timbuktu set in the city in 1940 was filmed in Kanab Utah. It starred Victor Mature and Yvonne de Carlo.

The American alternative pop group "Timbuk3", best known for their hit single "The Future's So Bright, I Gotta Wear Shades", derived their name as wordplay on the pronunciation of Timbuktu. San Francisco based messenger bag manufacturer Timbuk2 derived their name via a similar wordplay.[54]

In a Dutch Donald Duck comic subseries situated in Timbuktu, Donald Duck uses the city as a safe haven.[55] In the 1970 Disney animated feature The Aristocats, Edgar the butler places the cats in a trunk which he plans to send to Timbuktu. It is mistakenly noted to be in French Equatorial Africa, instead of French West Africa.[56]

Timbuktu also makes an appearance in the British musical Oliver! when Oliver sings to Nancy, "I'd do anything for you, dear, anything, for you" to which Nancy sings in reply, "Paint your face bright blue?" "Anything", Oliver responds. "Go to Timbuktu?" Nancy asks. "And back again", Oliver responds, and the song continues.

In Tom Robbins' novel Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas, Timbuktu provides a central theme. One lead character, Larry Diamond, is vocally fascinated with the city, due in large part to its rich history and supernatural significance.

Due to these cultural influences, Timbuktu has laid provenance to a host of colloquial language and expressions. For instance, one may often use the phrase "to go to Timbuktu" or "it is in Timbuktu" the like to connote that something is distant or hard to obtain.

Sister cities

Timbuktu is twinned to the following cities:[57]

- Chemnitz, Germany

- Chemnitz, Germany - Hay-on-Wye, Wales, United Kingdom

- Hay-on-Wye, Wales, United Kingdom - Marrakech, Morocco

- Marrakech, Morocco - Saintes, France

- Saintes, France - Tempe, Arizona, United States

- Tempe, Arizona, United States

Notes

- ↑ Resultats Provisoires RGPH 2009 (Région de Tombouctou), République de Mali: Institut National de la Statistique, http://instat.gov.ml/contenu_documentation.aspx?type=23

- ↑ Timbuktu — World Heritage (Unesco.org)

- ↑ Timbuktu. (2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Okolo Rashid. Legacy of Timbuktu: Wonders of the Written Word Exhibit - International Museum of Muslim Cultures [1]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 History of Timbuktu, Mali - Timbuktu Educational Foundation

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Early History of Timbuktu - The History Channel Classroom

- ↑ Homer, Curry. Snatched from the Serpent. Berrien Springs, Michigan: Frontiers Adventist. http://www.adventistfrontiers.com/article.php?id=3715.

- ↑ Demhardt, Imre Josef (August 2006). "Hopes, Hazards and a Haggle: Perthes' Ten Sheet "Karte von Inner-Afrika"". International Symposium on "Old Worlds-New Worlds": The History of Colonial Cartography 1750-1950 (August 21–23). Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands: Working Group on the History of Colonial Cartography in the 19th and 20th centuries International Cartographic Association (ICA-ACI). pp. 16. http://www.icahistcarto.org/PDF/Demhardt_Imre_-_Hopes_Hazards_and_a_Haggle.pdf.

- ↑ Mann, Kenny (1996). hana Mali Songhay: The Western Sudan. (African Kingdoms of the Past Series). South Orange, New Jersey: Dillon Press.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hunwick 1999, p. 444

- ↑ Bosworth, Edmund C. (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 521–522. ISBN 9004153888. http://books.google.nl/books?id=UB4uSVt3ulUC&pg=PA521&lpg=PA521&dq=maghsharan+tuareg&source=bl&ots=FBL1zN3mBM&sig=SKjvoNVCarIMobF6ufIo0itWwx4&hl=nl&ei=T_1ES8LZKs6k4QaBwvGpCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CA8Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=maghsharan%20tuareg&f=false.

- ↑ "Timbuktu". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/596022/Timbuktu. Retrieved 9 Januari 2010.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Boddy-Evans, Alistair. "Timbuktu: The El Dorado of Africa". About.com Guide. http://africanhistory.about.com/od/mali/p/Timbuktu.htm. Retrieved 7 Februari 2010.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Timbuktu Hopes Ancient Texts Spark a Revival". New York Times. August 7, 2007. "The government created an institute named after Ahmed Baba, Timbuktu's greatest scholar, to collect, preserve and interpret the manuscripts."

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Entry on Timbuktu at Archnet.com, http://www.archnet.org/library/places/one-place.jsp?place_id=2181&order_by=title&showdescription=1, retrieved 12 February 2010

- ↑ "TIMBUKTU (French spelling Tombouctou)". Encyclopædia Britannica. V26. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. 1911. pp. 983. http://encyclopedia.jrank.org/THE_TOO/TIMBUKTU_French_spelling_Tombou.html. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Larry Brook, Ray Webb (1999) Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Timbuktu. Retrieved d.d. September 22, 2009.

- ↑ de Vries, Fred (7 Januari 2006). "Randje woestijn" (in Dutch). de Volkskrant (Amsterdam: PCM Uitgevers). http://www.volkskrant.nl/archief_gratis/article559535.ece/Randje_woestijn. Retrieved 7 Februari 2010.

- ↑ Fleming F. Off the Map. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004. pp. 245–249. ISBN 0-87113-899-9.

- ↑ Caillié 1830

- ↑ Calhoun, Warren Glenn; From Here to Timbuktu, p. 273 ISBN 0-7388-4222-2

- ↑ Sandford, Charles Adams; Robert Adams (2005). The Narrative of Robert Adams, a Barbary Captive: Critical Edition. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. XVIII (preface). ISBN 978-0-521-84284-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=hvwIko-0YLsC&pg=PR45&lpg=PR45&dq=The+Narrative+of+Robert+Adams,+a+Barbary+Captive+authencity&source=bl&ots=ZHeo48sCmC&sig=-8Xi5BBR3upBfGDcoIK_yh2fZkQ&hl=nl&ei=ejJvS6r6NInK-QaQpKT0DQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CAkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=authenticity&f=false.

- ↑ Barth 1857, p. 534 Vol. 1

- ↑ Buisseret, David (2007), "Oskar Lenz", The Oxford companion to world exploration, 1, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 465–466, http://books.google.com/books?id=xyAjAQAAIAAJ&q=The+Oxford+companion+to+world+exploration,+Volume+1+By+David+Buisseret,+Newberry+Library&dq=The+Oxford+companion+to+world+exploration,+Volume+1+By+David+Buisseret,+Newberry+Library&lr=&ei=d_ryS7anFKrKzASX_diGDQ&cd=1

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Pelizzo, Riccardo (2001). "Timbuktu: A Lesson in Underdevelopment". Journal of World-Systems Research 7 (2): 265–283. http://jwsr.ucr.edu/archive/vol7/number2/pdf/jwsr-v7n2-pelizzo.pdf. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ↑ Maugham, Reginal Charles Fulke (Januari 1924). "NATIVE LAND TENURE IN THE TIMBUKTU DISTRICTS". Journal of the Royal African Society (London: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Royal African Society) 23 (90): 125–130. http://www.jstor.org/stable/715389. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ Neumann, Bernard de (1 November 2008), British Merchant Navy Graves in Timbuktu, http://www.gordonmumford.com/m-navy/pow-2.htm, retrieved 17 February 2010

- ↑ Lacey, Montague (10 February 1943). "The Man from Timbuctoo". Daily Express (London: Northern and Shell Media): pp. 1. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/stories/89/a8027589.shtml. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ↑ Arts & Life in Africa, 15 October 1998, http://www.uiowa.edu/~africart/toc/countries/Mali.html, retrieved 20 February 2010

- ↑ Brooke, James (23 March 1988). "Timbuktu Journal; Sadly, Desert Nomads Cultivate Their Garden". New York Times (New York City, NY: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr.). http://www.nytimes.com/1988/03/23/world/timbuktu-journal-sadly-desert-nomads-cultivate-their-garden.html?pagewanted=1. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ↑ Collins, Robert O. (1990) Western African History, London: Markus Wiener Publishers.

- ↑ Leo Africanus 1896, p. 3

- ↑ Cissoko, S.M (1996). Toumbouctou et l’ Empire Songhai. Paris: L’ Harmattan

- ↑ Bovill, E. W. (1921). The Encroachment of the Sahara on the Sudan, Journal of the African Society 20: p. 174-185

- ↑ Leo Africanus 1896, pp. Vol. 3

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Brians, Paul (1998). Reading About the World. Fort Worth, TX, USA: Harcourt Brace College Publishing. pp. vol. II. http://www.wsu.edu:8080/~wldciv/world_civ_reader/world_civ_reader_2/leo_africanus.html.

- ↑ Freeman, Shane (2008). "Leo Africanus Describes Timbuktu". North Carolina Digital History. University of North Carolina. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-colonial/1982. Retrieved 25 april 2010.

- ↑ Insoll 2004

- ↑ Jackson, James Grey (1820). An Account of Timbuctoo and Housa, Territories in the Interior of Africa By El Hage Abd Salam Shabeeny. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. http://books.google.nl/books?id=BAtFAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=james+grey+jackson&source=bl&ots=ZVeHKLx10O&sig=C8kLp2-9jIvKShmpT4-E4_eW2u8&hl=en&ei=MiTsS-39DJCmOPTz9NkH&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=timbuctoo&f=false.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Jeppie, Shamil (ed); Diagen, Souleymane; McIntosh, Roderick J; Bloom, Jonathan M; Blair, Sheila S; Cleaveland, Timothy; Farias, Paulo de Moraes; Hassane, Moulaye; Boboyyi, Hamid; Last, Murray; Mack, Beverly B; Farouk-Alli, Aslam; Mathee, Shaheed, Mathee; el-Bara, Yahya Ould (2008). "6". The Meanings of Timbuktu. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press. pp. 77–91. http://www.hsrcpress.ac.za/product.php?productid=2216&cat=2&page=2&featured&js=y&freedownload=1.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Huddleston, Alexandra (1 September 2009). "Divine Learning: The Traditional Islamic Scholarship of Timbuktu". Fourth Genre: Explorations in Non-Fiction (Michigan, MI, USA: Michigan State University Press) 11 (2): 129–135. ISSN 1522-3868. http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.library.wur.nl/. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ↑ Holbrook, Jarita;, Jarita; Urama, Johnson; Medupe, R. Thebe, Warner, Brian; Jeppie, Shamil; Sanogo, Salikou; Maiga, Mohammed; Dembele, Mamadou; Diakite, Drissa; Tembely, Laya; Kanoute, Mamadou; Traore, Sibiri; Sodio, Bernard; Hawkes, Sharron (1 January 2008). The Timbuktu Astronomy Project. Leiden, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands. http://www.springerlink.com.ezproxy.library.wur.nl/content/p17743321v735124/.

- ↑ Makdisi, George (April-June 1989), "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West", Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 109 (2): 175–182 [176], doi:10.2307/604423, http://jstor.org/stable/604423

- ↑ University of Timbuktu, Mali - Timbuktu Educational Foundation

- ↑ Rainier, Chris (27 May 2003). "Reclaiming the Ancient Manuscripts of Timbuktu". National Geographic News. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/05/0522_030527_timbuktu.html. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ Grant, Simon (8 February 2007), "Beyond the Saharan Fringe", The Guardian, http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/booksblog/2007/feb/08/beyondthesaharanfringe, retrieved 19 July 2010

- ↑ Abraham, Curtis (15 August 2007). "Stars of the Sahara". New Scientist (London: Reed Elsevier) 2617: 37–39. http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19526171.400. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ 2007

- ↑ UNESCO July 10, 2008.

- ↑ Salak, Kira. "Photos from "KAYAKING TO TIMBUKTU"". National Geographic Adventure. http://www.kirasalak.com/PhotosMali.html.

- ↑ World Weather Information Service - Tombouctou, World Meteorological Organization, http://www.worldweather.org/034/c00134.htm, retrieved 2009-10-19

- ↑ "Search on for Timbuktu's twin" BBC News, 18 October 2006. Retrieved 28 March 2007

- ↑ "Timbuktu official website". http://timbuktu.bandcamp.com/. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Timbuk2 corporate website". http://www.timbuk2.com. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Donald Duck Timboektoe subseries (Dutch) on the C.O.A. Search Engine (I.N.D.U.C.K.S.). Retrieved d.d. October 24, 2009.

- ↑ Notes on The Aristocats at the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 24, 2009

- ↑ "Timbuktu 'twins' make first visit". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 October 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/wales/mid_/7058884.stm. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

References

- Barth, Heinrich (1857), Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa: Being a journal of an expedition undertaken under the auspices of H. B. M.'s government, in the years 1849-1855. (3 Vols), New York: Harper & Brothers. Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3.

- Caillié, Réné (1830), Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo; and across the Great Desert, to Morocco, performed in the years 1824-1828 (2 Vols), London: Colburn & Bentley. Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2.

- Dubois, Felix; White, Diana (trans.) (1896), Timbuctoo the mysterious, New York: Longmans, http://www.archive.org/details/timbuctoomyster01whitgoog.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005), The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-24385-4. Originally published in 1986, ISBN 0-520-05771-6.

- Hacquard, Augustin (1900), Monographie de Tombouctou, Paris: Société des études coloniales & maritimes, http://www.archive.org/details/monographiedeto00hacqgoog.

- Hunwick, John O. (1999), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9004112073. Pages 272-291 contain a translation into English of Leo Africanus' descriptions of the Middle Niger, Hausaland and Bornu.

- Hunwick, John O.; Boye, Alida Jay; Hunwick, Joseph (2008), The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Historic city of Islamic Africa, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-51421-4.

- Insoll, Timothy (2001-2002), "The archaeology of post-medieval Timbuktu", Sahara 13: 7–11, http://www.insoll.org/Timbuktu%20Sahara.pdf.

- Insoll, Timothy (2004), "Timbuktu the less Mysterious?", in Mitchell, P.; Haour, A.; Hobart, J., Researching Africa's Past. New Contributions from British Archaeologists, Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 81–88, http://www.insoll.org/Timbuktu%20Oxford%20Vol.pdf.

- Leo Africanus (1896), The History and Description of Africa (3 Vols), Brown, Robert, editor, London: Hakluyt Society. A facsimile of Pory's English translation of 1600 together with an introduction and notes by the editor. Internet Archive: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973), Ancient Ghana and Mali, London: Methuen, ISBN 0841904316, http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.sip100013. Link requires subscription to Aluka.

- Miner, Horace (1953), The primitive city of Timbuctoo, Princeton University Press, http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.sip200008. Link requires subscription to Aluka. Reissued by Anchor Books, New York in 1965.

- Saad, Elias N. (1983), Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-5212-4603-2.

- Trimingham, John Spencer (1962), A History of Islam in West Africa, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-1928-50385.

Further reading

- Braudel, Fernand, 1979 (in English 1984). The Perspective of the World, vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism

- Houdas, Octave (ed. and trans.) (1901), Tedzkiret en-nisiān fi Akhbar molouk es-Soudān, Paris: E. Laroux, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5444371d.r=houdas.langEN. The anonymous 18th century Tadhkirat al-Nisyan is a biographical dictionary of the pashas of Timbuktu from the Moroccan conquest up to 1750.

- Jenkins, Mark, (June 1997) To Timbuktu, ISBN 978-0-688-11585-2 William Marrow & Co. Revealing travelogue along the Niger to Timbuktu

- Pelizzo, Riccardo, Timbuktu: A Lesson in Underdevelopment, Journal of World System Research, vol. 7, n.2, 2001, pp. 265–283, jwsr.ucr.edu/archive/vol7/number2/pdf/jwsr-v7n2-pelizzo.pdf

External links

- Saharan Archaeological Research Association - Directed by Douglas Post Park, and Peter Coutros of Yale University.

- Leo Africanus, description of Timbuktu, 1526

- Shabeni's Description of Timbuktu

- "Trekking to Timbuktu", a National Endowment for the Humanities learning project for grades 6-8

- Wonders of the African World

- The University of Sankore at Timbuktu

- The Timbuktu Libraries

- List of publications on Timbuktu. Centre for Development and the Environment, University of Oslo

- Saving Mali's written treasures

- Ancient Manuscripts from the Desert Libraries of Timbuktu, Library of Congress — exhibition of manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library

- Islamic Manuscripts from Mali, Library of Congress — fuller presentation of the same manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library

- "How a small African desert town is changing perceptions of the East", from Toplum Postasi, 11 July 2007

- Timbuktu materials in the Aluka digital library

Tourism

- Timbuktu travel guide from Wikitravel

- map of Timbuktu (from Norway, in French)

- Pictures of Timbuktu

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||