Tracheotomy

| Intervention: Tracheotomy |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

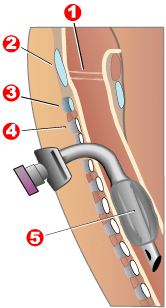

| Completed tracheotomy: 1 - Vocal folds |

||

| ICD-10 code: | ||

| ICD-9 code: | 31.1 | |

| MeSH | D014140 | |

| Other codes: | ||

Among the oldest described surgical procedures, tracheotomy (also referred to as pharyngotomy, laryngotomy, and tracheostomy) consists of making an incision on the anterior aspect of the neck and opening a direct airway through an incision in the trachea. The resulting stoma can serve independently as an airway or as a site for a tracheostomy tube to be inserted; this tube allows a person to breathe without the use of their nose or mouth. Both surgical and percutaneous techniques are widely used in current surgical practice.

Contents |

Etymology and terminology

The etymology of the word tracheotomy comes from two Greek words: the root tom- meaning "to cut", and the word trachea.[1] The word tracheostomy, including the root stom- meaning "mouth," refers to the making of a semi-permanent or permanent opening, and to the opening itself. Some sources offer different definitions of the above terms. Part of the ambiguity is due to the uncertainty of the intended permanence of the stoma at the time it is created.[2]

History

Prior to 16th century

Tracheotomy was first depicted on Egyptian artifacts in 3600 BCE.[3] It was described in the Rigveda, a Sanskrit text, circa 2000 BCE.[3] Homerus of Byzantium is said to have written of Alexander the Great saving a soldier from suffocation in 1000 BCE by making an incision with the tip of his sword in the man's trachea.[3] Hippocrates condemned the practice of tracheotomy as incurring an unacceptable risk of damage to the carotid artery. Warning against the possibility of death from inadvertent laceration of the carotid artery during tracheotomy, he instead advocated the practice of tracheal intubation.[4] Because surgical instruments were not sterilized at that time, infections following surgery also produced numerous complications, including dyspnea, often leading to death.[5]

Despite the concerns of Hippocrates, it is believed that an early tracheotomy was performed by Asclepiades of Bithynia, who lived in Rome around 100 BCE. Galen and Aretaeus, both of whom lived in Rome in the second century AD, credit Asclepiades as being the first physician to perform a non-emergency tracheotomy. Antyllus, another Roman physician of the second century AD, supported tracheotomy when treating oral diseases. He refined the technique to be more similar to that used in modern times, recommending that a transverse incision be made between the third and fourth tracheal rings for the treatment of life-threatening airway obstruction.[4] Antyllus (whose original writings were lost but not before they were preserved by the Greek historian Oribasius) wrote that tracheotomy was not effective however in cases of severe laryngotracheobronchitis because the pathology was distal to the operative site.[5] In AD 131, Galen clarified the anatomy of the trachea and was the first to demonstrate that the larynx generates the voice.

During the Middle Ages, scientific discoveries were few and far between in much of Europe. However, the scientific culture flourished in other parts of the world. By AD 700, the tracheotomy was well described in Indian and Arabian literature, although it was rarely practiced on humans.[5] In 1000, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (936-1013), an Arab who lived in Arabic Spain, published the 30-volume Kitab al-Tasrif, the first illustrated work on surgery. He never performed a tracheotomy, but he did treat a slave girl who had cut her own throat in a suicide attempt. Al-Zahrawi (known to Europeans as Albucasis) sewed up the wound and the girl recovered, thereby proving that an incision in the larynx could heal. Circa AD 1020, Avicenna (980-1037) described tracheal intubation in The Canon of Medicine in order to facilitate breathing.[6] The first correct description of the tracheotomy operation for treatment of asphyxiation was described by Ibn Zuhr in the 12th century,[7] Ibn Zuhr (1091-1161 A.D., also known as Avenzoar) successfully practiced the tracheotomy procedure on a goat, justifying Galen's approval of the operation.

16th-18th centuries

The European Renaissance brought with it significant advances in all scientific fields, particularly surgery. Increased knowledge of anatomy was a major factor in these developments. Surgeons became increasingly open to experimental surgery on the trachea. During this period, many surgeons attempted to perform tracheotomies, for various reasons and with various methods. Many suggestions were put forward, but little actual progress was made toward making the procedure more successful. The tracheotomy remained a dangerous operation with a very low success rate, and many surgeons still considered the tracheotomy to be a useless and dangerous procedure. The high mortality rate for this operation, which had not improved, supports their position.

From the period 1500 to 1832 there are only 28 known reports of tracheotomy.[8] In 1543, Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) wrote that tracheal intubation and subsequent artificial respiration could be life-saving. Antonio Musa Brassavola (1490-1554) of Ferrara treated a patient suffering from peritonsillar abscess by tracheotomy after the patient had been refused by barber surgeons. The patient apparently made a complete recovery, and Brassavola published his account in 1546. This operation has been identified as the first recorded successful tracheostomy, despite many ancient references to the trachea and possibly to its opening.[8] Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) described suture of tracheal lacerations in the mid-1500s. One patient survived despite a concomitant injury to the internal jugular vein. Another sustained wounds to the trachea and esophagus and died.

Towards the end of the 16th century, anatomist and surgeon Hieronymus Fabricius (1533–1619) described a useful technique for tracheotomy in his writings, although he had never actually performed a the operation himself. He advised using a vertical incision and was the first to introduce the idea of a tracheostomy tube. This was a straight, short cannula that incorporated wings to prevent the tube from advancing too far into the trachea. He recommended the operation only as a last resort, to be used in cases of airway obstruction by foreign bodies or secretions. He counseled that the operation should be performed only as a last option.[5] Fabricius' description of the tracheotomy procedure is similar to that used today. Julius Casserius (1561-1616) succeeded Fabricius as professor of anatomy at the University of Padua and published his own writings regarding technique and equipment for tracheotomy. Casserius recommended using a curved silver tube with several holes in it. Marco Aurelio Severino (1580-1656), a skillful surgeon and anatomist, performed multiple successful tracheotomies during a diphtheria epidemic in Naples in 1610, using the vertical incision technique recommended by Fabricius. He also developed his own version of a trocar.[9]

In 1620 the French surgeon Nicholas Habicot (1550-1624), surgeon of the Duke of Nemours and anatomist, published a report of four successful "bronchotomies" which he had performed.[10] One of these is the first recorded case of a tracheotomy for the removal of a foreign body, in this instance a blood clot in the larynx of a stabbing victim. He also described the first tracheotomy to be performed on a pediatric patient. A 14 year old boy swallowed a bag containing 9 gold coins in an attempt to prevent its theft by a highwayman. The object became lodged in his esophagus, obstructing his trachea. Habicot performed a tracheotomy, which allowed him to manipulate the bag so that it passed through the boy's alimentary tract, apparently with no further sequelae.[5] Habicot suggested that the operation might also be effective for patients suffering from inflammation of the larynx. He developed equipment for this surgical procedure which displayed similarities to modern designs (except for his use of a single-tube cannula).

Sanctorius (1561-1636) is believed to be the first to use a trocar in the operation, and he recommended leaving the cannula in place for a few days following the operation.[11] Early tracheostomy devices are illustrated in Habicot’s Question Chirurgicale[10] and Julius Casserius' posthumous Tabulae anatomicae in 1627.[12] Thomas Fienus (1567-1631), Professor of Medicine at the University of Louvain, was the first to use the word "tracheotomy" in 1649, but this term was not commonly used until a century later.[13] Georg Detharding (1671-1747), professor of anatomy at the University of Rostock, treated a drowning victim with tracheostomy in 1714.[14][15][16]

19th century

In the 1820s, the tracheotomy began to be recognized as a legitimate means of treating severe airway obstruction. In 1832, French physician Pierre Bretonneau employed it as a last resort to treat a case of diphtheria.[17] In 1852, Bretonneau's student Armand Trousseau reported a series of 169 tracheotomies (158 of which were for croup, and 11 for "chronic maladies of the larynx")[18] In 1869, the German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg reported the first successful elective human tracheotomy to be performed for the purpose of administration of general anesthesia. In 1878, the Scottish surgeon William Macewen reported the first orotracheal intubation. At last, in 1880 Morrell Mackenzie's book discussed the symptoms indicating a tracheotomy and when the operation is absolutely necessary.[4]

20th century

In the early 20th century, physicians began to use the tracheotomy in the treatment of patients afflicted with paralytic poliomyelitis who required mechanical ventilation. However, surgeons continued to debate various aspects of the tracheotomy well into the 20th century. Many techniques were described and employed, along with many different surgical instruments and tracheal tubes. Surgeons could not seem to reach a consensus on where or how the tracheal incision should be made, arguing whether the "high tracheotomy" or the "low tracheotomy" was more beneficial. The currently used surgical tracheotomy technique was described in 1909 by Chevalier Jackson of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Jackson emphasised the importance of postoperative care, which dramatically reduced the death rate. By 1965, the surgical anatomy was thoroughly and widely understood, antibiotics were widely available and useful for treating postoperative infections, and other major complications had also become more manageable.

Indications

In the acute setting, indications for tracheotomy include such conditions as severe facial trauma, head and neck cancers, large congenital tumors of the head and neck (e.g., branchial cleft cyst), and acute angioedema and inflammation of the head and neck. In the context of failed orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation, either tracheotomy or cricothyrotomy may be performed. In the chronic setting, indications for tracheotomy include the need for long-term mechanical ventilation and tracheal toilet (e.g. comatose patients, or extensive surgery involving the head and neck).

Surgical instruments

As with most other surgical procedures, some cases are more difficult than others. Surgery on children is more difficult because of their smaller size. Difficulties such as a short neck and bigger thyroid glands make the trachea hard to open.[19] There are other difficulties with patients with irregular necks, the obese, and those with a large goitre. The many possible complications include hemorrhage, loss of airway, subcutaneous emphysema, wound infections, stomal cellulites, fracture of tracheal rings, poor placement of the tracheotomy tube, and bronchospasm".[4]

By the late 19th century, some surgeons had become proficient in performing the tracheotomy. The main instruments used were:

“Two small scalpels, one short grooved director, a tenaculum, two aneurysm needles which may be used as retractors, one pair of artery forceps, haemostatic forceps, two pairs of dissecting forceps, a pair of scissors, a sharp-pointed tenotome, a pair of tracheal forceps, a tracheal dilator, tracheotomy tubes, ligatures, sponges, a flexible catheter, and feathers”.[19] Haemostatic forceps were used to control bleeding from separated vessels that were not ligatured because of the urgency of the operation. Generally, they were used to expose the trachea by clamping the isthmus thyroid gland on both sides. To open the trachea physically, a sharp-pointed tentome allowed the surgeon easily to place the ends into the opening of the trachea. The thin points permitted the doctor a better view of his incision. Tracheal dilators, such as the “Golding Bird”, were placed through the opening and then expanded by “turning the screw to which they are attached.” Tracheal forceps, as displayed on the right , were commonly used to extract foreign bodies from the larynx. The optimum tracheal tube at the time caused very little damage to the trachea and “mucus membrane”.[19]

The best position for a tracheotomy was and still is one that forces the neck into the biggest prominence. Usually, the patient was laid on his back on a table with a cushion placed under his shoulders to prop him up. The arms were restrained to ensure they would not get in the way later.[19] The tools and techniques used today in tracheotomies have come a long way. The tracheotomy tube placed into the incision through the windpipe comes in various sizes, thus allowing a more comfortable fit and the ability to remove the tube in and out of the throat without disrupting support from a breathing machine. In today’s world general anesthesia is used when performing these surgeries, which makes it much more tolerable for the patient. Special tubes have always been created to assist people in their speech. With these unique speaking tubes, people can breathe and talk through these tubes. When they exhale the air passes through the tube and vocal cords, producing sound.[20]

The tracheotomy underwent centuries of denial and rejection as well as much failure. Finally, in recent decades, it has become a commonly accepted, crucial, and successful surgery that has saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of patients.

Complications

In order to limit the risk of damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerves (the nerves that control the vocal folds), tracheotomy is performed as high in the trachea as possible. If only one of these nerves is damaged, the patient will experience dysphonia; if both of the nerves are damaged, the patient will experience complete aphonia. British theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking lost his speech after surgeons performed a tracheotomy in an effort to prevent recurrent pneumonia.[21]

A 2000 Spanish study of bedside percutaneous tracheostomy reported overall complication rates of 10–15% and procedural mortality of 0%,[22] which is comparable to those of other series reported in the literature from the Netherlands[23][24] and the United States.[25][26]

See also

- Laryngotomy

References

- ↑ Romaine F. Johnson (6 March 2003). "Adult Tracheostomy". Houston, Texas: Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine. http://www.bcm.edu/oto/grand/03_06_03.htm. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Jonathan P Lindman and Charles E Morgan (7 June 2010). "Tracheostomy". emedicine from WebMD. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/865068-overview. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Steven E. Sittig and James E. Pringnitz (February 2001). "Tracheostomy: evolution of an airway". AARC Times: 48–51. http://www.tracheostomy.com/resources/pdf/evolution.pdf. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Alfio Ferlito, Alessandra Rinaldo, Ashok R. Shaha, Patrick J. Bradley (December 2003). "Percutaneous Tracheotomy". Acta Otolaryngologica 123 (9): 1008–1012. doi:10.1080/00016480310000485. PMID 14710900. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a713714394. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 O. Rajesh & R. Meher (2006). "Historical Review Of Tracheostomy". The Internet Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 4 (2). ISSN 1528-8420. http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_otorhinolaryngology/volume_4_number_2_33/article/historical_review_of_tracheostomy.html. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Patricia Skinner (2008). "Unani-tibbi". In Laurie J. Fundukian. The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine (3rd ed.). Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale Cengage. ISBN 9781414448725. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_g2603/is_0007/ai_2603000716/. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Mostafa Shehata (April 2003). "The Ear, Nose and Throat in Islamic Medicine". Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine 2 (3): 2–5. ISSN 1303-667x. http://www.ishim.net/ishimj/3/01.pdf. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Goodall, E.W. (1934). "The story of tracheostomy". British Journal of Children's Diseases 31: 167–76, 253–72.

- ↑ Armytage WHG (1960). "Giambattista Della Porta and the segreti". British Medical Journal 1 (5179): 1129–1130. PMC 1966956. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1966956/pdf/brmedj02914-0083.pdf. Retrieved 02 September 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Nicholas Habicot (1620) (in French). Question chirurgicale par laquelle il est démonstré que le Chirurgien doit assurément practiquer l'operation de la Bronchotomie, vulgairement dicte Laryngotomie, ou perforation de la fluste ou du polmon. Paris: Corrozet. pp. 108.

- ↑ Sanctorii Sanctorii (1646) (in Latin). Sanctorii Sanctorii Commentaria in primum fen, primi libri canonis Avicennæ. Venetiis: Apud Marcum Antonium Brogiollum. pp. 1120. OCLC OL15197097M. http://openlibrary.org/works/OL5226737W/Sanctorii_Sanctorii_Commentaria_in_primum_fen_primi_libri_canonis_Auicennæ_... Retrieved 03 September 2010.

- ↑ Julius Casserius (Giulio Casserio) and Daniel Bucretius (1632) (in Latin). Tabulae anatomicae LXXIIX … Daniel Bucretius … XX. que deerant supplevit & omnium explicationes addidit. Francofurti: Impensis & coelo Matthaei Meriani. http://www.antiqbook.com/boox/gac/089233.shtml. Retrieved 03 September 2010.

- ↑ Cawthorne T, Hewlett AB, Ranger D (1959). "Tracheostomy in a Respiratory Unit at a Neurological Hospital". Procedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 52 (6): 403-405. PMID 13667911. PMC 1871130. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1871130/pdf/procrsmed00269-0031.pdf. Retrieved 03 September 2010.

- ↑ Georges Detharding (1745). "De methodo subveniendi submersis per laryngotomiam (1714)". In Von Ernst Ludwig Rathlef, Gabriel Wilhelm Goetten, Johann Christoph Strodtmann. Geschichte jetzlebender Gelehrten, als eine Fortsetzung des Jetzlebenden. Zelle: Berlegts Joachim Undreas Deek. pp. 20. http://books.google.de/books?id=flM5AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA6#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 04 September 2010.

- ↑ Price JL (1962). "THE EVOLUTION OF BREATHING MACHINES". Medical History 6 (1): 67-72. PMC 1034674. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1034674/pdf/medhist00168-0076.pdf. Retrieved 04 September 2010.

- ↑ Wischhusen HG (1977). "Curriculum vitae of the professor of anatomy, botany and higher mathematics Georg Detharding (1671-1747) at the University of Rostock" (in German). Anat Anz 142 (1-2): 133-140. PMID 339777. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/339777. Retrieved 04 September 2010.

- ↑ Armand Trousseau (1833). "Mémoire sur un cas de tracheotomie pratiquée dans la période extrème de croup". Journal des connaissances médico-chirurgicales 1 (5): 41.

- ↑ Armand Trousseau (1852). "Nouvelles recherches sur la trachéotomie pratiquée dans la période extrême du croup". In Jean Lequime and J. de Biefve. Annales de médecine belge et étrangère. Brussels: Imprimerie et Librairie Société Encyclographiques des Sciences Médicales. pp. 279–288. http://books.google.com/?id=khsUAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA279&lpg=PA279&dq=%22Nouvelles+recherches+sur+la+trach%C3%A9otomie+pratiqu%C3%A9e+dans+la+p%C3%A9riode+extr%C3%AAme+du+croup%22&q=%22Nouvelles%20recherches%20sur%20la%20trach%C3%A9otomie%20pratiqu%C3%A9e%20dans%20la%20p%C3%A9riode%20extr%C3%AAme%20du%20croup%22. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Wharton, Henry R. (January 1897). "Minor Surgery and Bandaging". American Journal of the Medical Sciences 113 (1): 104–106. doi:10.1097/00000441-189701000-00008. http://journals.lww.com/amjmedsci/Citation/1897/01000/Minor_Surgery_and_Bandaging.8.aspx. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ James H. Cullen (01 June 1963). "An Evaluation of Tracheostomy in Pulmonary Emphysema". Annals of Internal Medicine 58 (6): 953–960. PMID 14024192. http://www.annals.org/content/58/6/953.extract. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Stephen W. Hawking (1 February 2008). "Disability Advice". http://www.hawking.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=51&Itemid=55. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Añón, José M.; Gómez, Vicente; Escuela, Maria Paz et al. (2000). "Percutaneous tracheostomy: comparison of Ciaglia and Griggs techniques". Critical Care 4 (2): 124–8. doi:10.1186/cc667. PMID 11056749.

- ↑ Van Heurn, L. W.; van Geffen, G. J.; Brink, P. R. (1996). "Clinical experience with percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy: report of 150 cases". European Journal Surgery 162 (7): 531–5. PMID 8874159.

- ↑ Polderman, Kees H.; Spijkstra, Jan Jaap; de Bree, Remco et al. (2003). "Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy in the ICU: optimal organization, low complication rates, and description of a new complication". Chest 123 (5): 1595–602. doi:10.1378/chest.123.5.1595. PMID 12740279.

- ↑ Hill, Bradley B.; Zweng, Thomas N.; Maley, Richard H. et al. (1996). "Percutaneous dilational tracheostomy: report of 356 cases". Journal of Trauma 41 (2): 238–43. doi:10.1097/00005373-199608000-00007. PMID 8760530.

- ↑ Powell, David M.; Price, Phillip D.; Forrest, L. Arick (1998). "Review of percutaneous tracheostomy". The Laryngoscope 108 (2): 170–7. doi:10.1097/00005537-199802000-00004. PMID 9473064.

External links

- Tracheotomy Info (A Community For Tracheotomy-wearers and the people who love them) at tracheotomy.info

- Aaron's tracheostomy page (Caring for a tracheostomy) at tracheostomy.com

- How to perform an emergency tracheotomy (This page actually depicts cricothyroidotomy, not tracheostomy)

- RT Corner (Educational Site for RT's and Nurses) at rtcorner.net

- (Pictures with video clipping) at drtbalu.com

- Tracheotomy at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Smiths Medical Tracheostomy Training Videos

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||