Hyperthermia

|

An analog medical thermometer showing a temperature of 38.7 °C (101.7 °F) |

|

| ICD-9 | 780.6 |

|---|---|

| DiseasesDB | 18924 |

| MeSH | D005334 |

Hyperthermia is an elevated body temperature due to failed thermoregulation. Hyperthermia occurs when the body produces or absorbs more heat than it can dissipate. When the elevated body temperatures are sufficiently high, hyperthermia is a medical emergency and requires immediate treatment to prevent disability and death.

The most common causes are heat stroke and adverse reactions to drugs. Heat stroke is an acute condition of hyperthermia that is caused by prolonged exposure to excessive heat and/or humidity. The heat-regulating mechanisms of the body eventually become overwhelmed and unable to effectively deal with the heat, causing the body temperature to climb uncontrollably. Hyperthermia is a relatively rare side effect of many drugs, particularly those that affect the central nervous system. Malignant hyperthermia is a rare complication of some types of general anesthesia.

Hyperthermia can be created artificially by drugs or medical devices. Hyperthermia therapy may be used to treat some kinds of cancer and other conditions, most commonly in conjunction with radiotherapy.[1]

Hyperthermia differs from fever in the mechanism that causes the elevated body temperatures: a fever is caused by a change in the body's temperature set-point.

The opposite of hyperthermia is hypothermia, which occurs when an organism's temperature drops below that required for normal metabolism. Hypothermia is caused by prolonged exposure to low temperatures and is also a medical emergency requiring immediate treatment.

Contents |

Classification

| Temperature Classification | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Hypothermia | <35.0 °C (95.0 °F)[2] |

| Normal | 36.5–37.5 °C (98–100 °F)[3] |

| Fever | >37.5–38.3 °C (100–101 °F)[4][5] |

| Hyperthermia | >38.4–39.9 °C (101–104 °F)[4][5] |

| Hyperpyrexia | >40.0–41.5 °C (104–107 °F)[6][7] |

Hyperthermia is defined as a temperature greater than 37.5–38.3 °C (100–101 °F), depending on the reference, that occurs without a change in the body's temperature set-point.[4][5]

The normal human body temperature in a healthy adult can be as high as 37.7 °C (99.9 °F) in the late afternoon.[8] Hyperthermia requires an elevation from the temperature that would otherwise be expected. Such elevations range from mild to extreme; body temperatures above 40 °C (104 °F) can be life-threatening.

Signs and symptoms

Hot, dry skin is a typical sign of hyperthermia.[8] The skin may become red and hot as blood vessels dilate in an attempt to increase heat dissipation, sometimes leading to swollen lips. An inability to cool the body through perspiration causes the skin to feel dry.

Other signs and symptoms vary depending on the cause. The dehydration associated with heat stroke can produce nausea, vomiting, headaches, and low blood pressure. This can lead to fainting or dizziness, especially if the person stands suddenly.

In the case of severe heat stroke, the person may become confused or hostile, and may seem intoxicated. Heart rate and respiration rate will increase (tachycardia and tachypnea) as blood pressure drops and the heart attempts to supply enough oxygen to the body. The decrease in blood pressure can then cause blood vessels to contract, resulting in a pale or bluish skin color in advanced cases of heat stroke. Some victims, especially young children, may have seizures. Eventually, as body organs begin to fail, unconsciousness and coma will result.

Causes

Heat stroke

Heat stroke is due to an environmental exposure to heat, resulting in an abnormally high body temperature.[8] In severe cases, temperatures can exceed 40 °C (104 °F).[9] Heat stroke may be exertional or non-exertional, depending on whether the person has been exercising in the heat. Significant physical exertion on a very hot day can generate heat beyond a healthy body's ability to cool itself, because the heat and humidity of the environment reduces the efficiency of the body's normal cooling mechanisms.[8] Other factors, such as drinking too little water, can exacerbate the condition. Non-exertional heat stroke is typically precipitated by medications that reduce vasodilation, sweating, and other heat-loss mechanisms, such as anticholingeric drugs, antihistamines, and diuretics.[8] In this situation, the body's tolerance for the excessive environmental temperatures can be too limited to cope with the heat, even while resting.

Drugs

Some drugs cause excessive internal heat production, even in normal temperature environments.[8] The rate of drug-induced hyperthermia is higher where use of these drugs is higher.[8]

- Many psychotropic medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and tricyclic antidepressants, can cause hyperthermia.[8] Serotonin syndrome often presents following exposure to multiple drugs. Similarly, neuroleptic malignant syndrome is an uncommon reaction to neuroleptic agents.[10] These syndromes are differentiated by the other associated symptoms, such as tremor in serotonin syndrome and "lead-pipe" muscle rigidity in neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[8]

- Many illicit drugs, including amphetamines,[11] cocaine,[12] PCP, LSD, and MDMA can produce hyperthermia as an adverse effect.[8]

- Malignant hyperthermia is a rare reaction to common anesthetic agents (such as halothane) or a reaction to the paralytic agent succinylcholine. Malignant hyperthermia is a genetic condition, and can be fatal.[8]

Personal protective equipment

People working in industry, the military and first responders must wear Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to protect themselves from hazardous threats such as chemical agents, gases, fire, small arms and even Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). This PPE can include a range of hazmat suits, firefighting turnout gear, body armor and bomb suits, among many other forms. Depending on its design, PPE often ‘encapsulates’ the wearer from a threat and creates what is known as a microclimate,[13] due to an increase in thermal resistance and decrease in vapor permeability. As a person performs physical work, the body’s natural method of thermoregulation (i.e., sweating) becomes ineffective. This is compounded by increased work rates, high ambient temperatures and humidity levels, and direct exposure to the sun. The net effect is that protection from one or more environmental threats inadvertently brings on the threat of heat stress.

Other

Other possible, but rare, causes of hyperthermia are thyrotoxicosis and the presence of a tumor on the adrenal gland, called a pheochromocytoma, both of which can cause increased heat production.[8] Damage to the central nervous system, such as from a brain hemorrhage, status epilepticus, and other kinds of damage to the hypothalamus can also cause hyperthermia.[8]

Pathophysiology

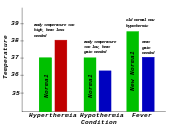

Hyperthermia: Characterized on the left. Normal body temperature (thermoregulatory set-point) is shown in green, while the hyperthermic temperature is shown in red. As can be seen, hyperthermia can be conceptualized as an increase above the thermoregulatory set-point.

Hypothermia: Characterized in the center: Normal body temperature is shown in green, while the hypothermic temperature is shown in blue. As can be seen, hypothermia can be conceptualized as a decrease below the thermoregulatory set-point.

Fever: Characterized on the right: Normal body temperature is shown in green. It reads "New Normal" because the thermoregulatory set-point has risen. This has caused what was the normal body temperature (in blue) to be considered hypothermic.

A fever occurs when the body sets the core temperature to a higher temperature, through the action of the pre-optic region of the anterior hypothalamus. For example, in response to a bacterial or viral infection, the body will raise its temperature, much like raising the temperature setting on a thermostat.

In contrast, hyperthermia occurs when the body temperature rises without a change in the heat control centers.

Some of the gastrointestinal symptoms of acute exertional heat stroke, such as vomiting, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal bleeding, may be caused by barrier dysfunction and subsequent endotoxemia. Ultraendurance athletes have been found to have significantly increased plasma endotoxin levels. Endotoxin stimulates many inflammatory cytokines, which in turn may cause multiorgan dysfunction. Furthermore, monkeys treated with oral antibiotics prior to induction of heat stroke do not become endotoxemic.[14]

Diagnosis

Hyperthermia is generally diagnosed in the presence of an unexpectedly high body temperature and a history that suggests hyperthermia instead of a fever.[8] Most commonly this means that the elevated temperature has appeared in a person that was working in a hot, humid environment (heat stroke) or that was taking a drug for which hyperthermia is a known side effect (drug-induced hyperthermia). The presence of other signs and symptoms related to hyperthermia syndromes, such as the extrapyramidal symptoms that are characteristic of neuroleptic malginant syndrome, and the absence of signs and symptoms more commonly related to infection-related fevers, are also considered in making the diagnosis.

If fever-reducing drugs lower the body temperature, even if the temperature does not return entirely to normal, then hyperthermia is excluded.[8]

Prevention

In cases where heat stress is caused by physical exertion, hot environments or wearing protective equipment it can be prevented or mitigated by taking frequent rest breaks, staying hydrated and carefully monitoring body temperature. However, in situations demanding prolonged exposure to a hot environment or wearing protective equipment, a personal cooling system is required as a matter of health and safety. A variety of active or passive technologies personal cooling systems[13] exist which can be categorized by their power sources and whether they are man or vehicle-mounted.

Due to the broad variety of operating conditions, a personal cooling system must meet specific requirements, such as the rate and duration of cooling, need for physical mobility and autonomy, access to power, and conformance with health & safety regulations. For example, active liquid systems operate on the basis of chilling water and circulating it through a garment that cools the skin surface area that it covers through conduction. This type of system has proven successful in certain Military, Law Enforcement and Industrial applications. Bomb disposal technicians wearing bomb suits to protect against an Improvised Explosive Device (IED) use a small, ice-based chiller unit strapped to their leg with a Liquid Circulating Garment, usually a vest, worn over their torso to maintain their core temperature at safe levels. By contrast, soldiers traveling in combat vehicles can face microclimate temperatures in excesss of 150 degrees Fahrenheit and require a multiple-user vehicle-powered cooling system with rapid connection capabilities. Requirements for Hazmat teams, the medical community and workers in heavy-industry will vary further.

Treatment

Treatment for hyperthermia depends on its cause, as the underlying cause must be corrected. Mild hyperthemia caused by exertion on a hot day might be adequately treated through self-care measures, such as drinking water and resting in a cool place. Hyperthermia that results from drug exposures is frequently treated by cessation of that drug, and occasionally by other drugs to counteract them. Fever-reducing drugs such as paracetamol and aspirin have no value in treating hyperthermia.[8]

When the body temperature is significantly elevated, mechanical methods of cooling are used to remove heat from the body and to restore the body's ability to regulate its own temperatures.[8] Passive cooling techniques, such as resting in a cool, shady area and removing clothing can be applied immediately. Active cooling methods, such as sponging the head, neck, and trunk with cool water, remove heat from the body and thereby speed the body's return to normal temperatures. Drinking water and turning a fan or dehumidifying air conditioning unit on the affected person may improve the effectiveness of the body's evaporative cooling mechanisms (sweating).

Sitting in a bathtub of tepid or cool water (immersion method) can remove a significant amount of heat in a relatively short period of time. However, immersion in very cold water is counterproductive, as it causes vasoconstriction in the skin and thereby prevents heat from escaping the body core. In exertional heat stroke, studies have shown that although there are practical limitations, cool water immersion is the most effective cooling technique and the biggest predictor of outcome is degree and duration of hyperthermia.[15] No superior cooling method found for nonexertional heat stroke.[16]

When the body temperature reaches about 40 C, or if the affected person is unconscious or showing signs of confusion, hyperthermia is considered a medical emergency that requires treatment in a proper medical facility. In a hospital, more aggressive cooling measures are available, including intravenous hydration, gastric lavage with iced saline, and even hemodialysis to cool the blood.[8]

Epidemiology

The frequency of environmental hyperthermia can vary significantly from year to year depending on factors such as heat waves.

See also

- Heat cramps

References

- ↑ Information from the U.S. National Cancer Institute

- ↑ Marx, John (2006). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. Mosby/Elsevier. p. 2239. ISBN 9780323028455.

- ↑ Karakitsos D, Karabinis A (September 2008). "Hypothermia therapy after traumatic brain injury in children". N. Engl. J. Med. 359 (11): 1179–80. PMID 18788094.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Axelrod YK, Diringer MN (May 2008). "Temperature management in acute neurologic disorders". Neurol Clin 26 (2): 585–603, xi. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2008.02.005. PMID 18514828.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Laupland KB (July 2009). "Fever in the critically ill medical patient". Crit. Care Med. 37 (7 Suppl): S273–8. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181aa6117. PMID 19535958.

- ↑ Manson's Tropical Diseases: Expert Consult. Saunders Ltd. 2008. pp. 1229. ISBN 1-4160-4470-1.

- ↑ Trautner BW, Caviness AC, Gerlacher GR, Demmler G, Macias CG (July 2006). "Prospective evaluation of the risk of serious bacterial infection in children who present to the emergency department with hyperpyrexia (temperature of 106 degrees F or higher)". Pediatrics 118 (1): 34–40. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2823. PMID 16818546.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 Fauci, Anthony, et al. (2008). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (17 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 117–121. ISBN 9780071466332.

- ↑ Tintinalli, Judith (2004). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1187. ISBN 0071388753.

- ↑ Tintinalli, Judith (2004). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1818. ISBN 0071388753.

- ↑ Marx, John (2006). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. Mosby/Elsevier. p. 2894. ISBN 9780323028455.

- ↑ Marx, John (2006). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. Mosby/Elsevier. p. 2388. ISBN 9780323028455.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 In-Theatre Microclimate Cooling, US Army Natik Soldier Centre, http://chppm-www.apgea.army.mil/heat/MicroclimateCoolingOptions_May_2007.pdf, retrieved 17 May 2010

- ↑ Lambert, Patrick. Role of gastrointestinal permeability in exertional heatstroke. Exercise and Sport Science Reviews. 32(4): 185-190. 2004

- ↑ Br J Sports Med 2005: review 17 papers on EHS from 1966-2003

- ↑ Bouchama A, Dehbi M. Cooling and hemodynamic management in heatstroke: practical recommendations. Crit Care. 11(3): R54. 2007

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- International Red Cross Information on Heat Stroke

- Hiking and Camping Note Book Heat Stroke Advice

- Environment Canada's Heat Index (humidex) Chart

- Working in Hot Environments, from the United States' National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

- Excessive Heat Events Guidebook, from the United States' Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- Enhanced Home & Family Heatwave Preparedness

- Cold Water Immersion: The Gold Standard for Exertional Heatstroke Treatment

- Physiological Responses to Exercise in the Heat -- Chapter 3 of Nutritional Needs in Hot Environments by the Institute of Medicine of the U.S. National Academies (of Science) (N.B.: entire book is available in HTML format via this link)