Rickets

| Rickets | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

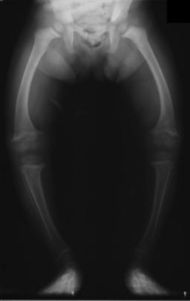

Radiograph of a two-year old rickets sufferer, with a marked genu varum (bowing of the femurs) and decreased bone opacity, suggesting poor bone mineralization. |

|

| ICD-10 | E55. |

| ICD-9 | 268 |

| DiseasesDB | 9351 |

| MedlinePlus | 000344 |

| eMedicine | ped/2014 |

| MeSH | D012279 |

Rickets is a softening of bones in children potentially leading to fractures and deformity. Rickets is among the most frequent childhood diseases in many developing countries. The predominant cause is a vitamin D deficiency, but lack of adequate calcium in the diet may also lead to rickets (cases of severe diarrhea and vomiting may be the cause of the deficiency). Although it can occur in adults, the majority of cases occur in children suffering from severe malnutrition, usually resulting from famine or starvation during the early stages of childhood. Osteomalacia is the term used to describe a similar condition occurring in adults, generally due to a deficiency of vitamin D.[1] The origin of the word "rickets" is probably from the Old English dialect word 'wrickken', to twist. The Greek derived word "rachitis" (ραχίτις, meaning "inflammation of the spine") was later adopted as the scientific term for rickets, due chiefly to the words' similarity in sound.

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of rickets include:

- Bone pain or tenderness

- dental problems

- muscle weakness (rickety myopathy or "floppy baby syndrome" or "slinky baby" (where the baby is floppy or slinky-like)

- increased tendency for fractures (easily broken bones), especially greenstick fractures

- Skeletal deformity

- Toddlers: Bowed legs (genu varum)

- Older children: Knock-knees (genu valgum) or "windswept knees"

- Cranial, spinal, and pelvic deformities

- Growth disturbance

- Hypocalcemia (low level of calcium in the blood), and

- Tetany (uncontrolled muscle spasms all over the body).

- Craniotabes (soft skull)

- Costochondral swelling (aka "rickety rosary" or "rachitic rosary")

- Harrison's groove

- Double malleoli sign due to metaphyseal hyperplasia

- Widening of wrist raises early suspicion, it is due to metaphysial cartilage hyperplasia.[1]

An X-ray or radiograph of an advanced sufferer from rickets tends to present in a classic way: bow legs (outward curve of long bone of the legs) and a deformed chest. Changes in the skull also occur causing a distinctive "square headed" appearance. These deformities persist into adult life if not treated.

Long-term consequences include permanent bends or disfiguration of the long bones, and a curved back.

Cause

The primary cause of rickets is a vitamin D deficiency. [2] Vitamin D is required for proper calcium absorption from the gut. Sunlight, especially ultraviolet light, lets human skin cells convert Vitamin D from an inactive to active state. In the absence of vitamin D, dietary calcium is not properly absorbed, resulting in hypocalcemia, leading to skeletal and dental deformities and neuromuscular symptoms, e.g. hyperexcitability. Foods that contain vitamin D include butter, eggs, fish liver oils, margarine, fortified milk and juice, and oily fishes such as tuna, herring, and salmon. A rare X-linked dominant form exists called Vitamin D resistant rickets.

Diagnosis

Rickets may be diagnosed with the help of:

- Blood tests:

- Serum calcium may show low levels of calcium, serum phosphorus may be low, and serum alkaline phosphatase may be high.

- Arterial blood gases may reveal metabolic acidosis

- X-rays of affected bones may show loss of calcium from bones or changes in the shape or structure of the bones.

- Bone biopsy is rarely performed but will confirm rickets.

Treatment and prevention

The treatment and prevention of rickets is known as antirachitic.

Diet and sunlight

Treatment involves increasing dietary intake of calcium, phosphates and vitamin D. Exposure to ultraviolet B light (sunshine when the sun is highest in the sky), cod liver oil, halibut-liver oil, and viosterol are all sources of vitamin D.

A sufficient amount of ultraviolet B light in sunlight each day and adequate supplies of calcium and phosphorus in the diet can prevent rickets. Darker-skinned babies need to be exposed longer to the ultraviolet rays. The replacement of vitamin D has been proven to correct rickets using these methods of ultraviolet light therapy and medicine.

Recommendations are for 400 international units (IU) of vitamin D a day for infants and children. Children who do not get adequate amounts of vitamin D are at increased risk of rickets. Vitamin D is essential for allowing the body to uptake calcium for use in proper bone calcification and maintenance.

Supplementation

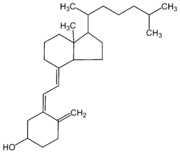

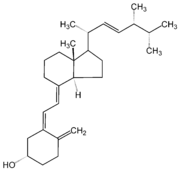

Sufficient vitamin D levels can also be achieved through dietary supplementation and/or exposure to sunlight. Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is the preferred form since it is more readily absorbed than vitamin D2. Most dermatologists recommend vitamin D supplementation as an alternative to unprotected ultraviolet exposure due to the increased risk of skin cancer associated with sun exposure. Note that in July in New York City at noon with the sun out, a white male in tee shirt and shorts will produce 20000 IU of Vitamin D from 20 minutes of non-sunscreen sun exposure.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), infants who are breast-fed may not get enough vitamin D from breast milk alone. For this reason, the AAP recommends that infants who are exclusively breast-fed receive daily supplements of vitamin D from age 2 months until they start drinking at least 17 ounces of vitamin D-fortified milk or formula a day.[3] This requirement for supplemental vitamin D is not a defect in the evolution of human breastmilk, but is instead a result of the modern-day infant's decreased exposure to sunlight (i.e. breast-fed infants who receive adequate sun exposure are less likely to develop rickets, though supplementation may still be indicated in the winter, depending on geographical latitude).

Child abuse and rickets

It has been hypothesized that symptoms of rickets (including the congenital form) may look like child abuse, as described in Rickets vs. abuse: a national and international epidemic. This contention remains purely speculative and unsupported by epidemiological medical literature or clinical practice.

Epidemiology

In developed contries, rickets is a rare disease[4] (incidence of less than 1 in 200,000).

Those at higher risk for developing rickets include:

- Breast-fed infants whose mothers are not exposed to sunlight

- Breast-fed infants who are not exposed to sunlight

- Babies with dark complexions (e.g. brown skin, South African), particularly when breastfed and exposed to little sunlight

- Individuals not consuming milk, such as those who are lactose intolerant

Individuals with red hair have been speculated to have a decreased risk for rickets due to their greater production of vitamin D in sunlight.

Children ages 6 months to 24 months are at highest risk, because their bones are rapidly growing. Long-term consequences include permanent bends or disfiguration of the long bones, and a curved back.

References

- ↑ MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Osteomalacia

- ↑ http://bone-muscle.health-cares.net/rickets-causes.php

- ↑ Gartner LM, Greer FR (April 2003). "Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency: new guidelines for vitamin D intake". Pediatrics 111 (4 Pt 1): 908–10. doi:10.1542/peds.111.4.908. PMID 12671133. http://aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;111/4/908.

- ↑ National Health Service of England > Rickets Last reviewed: 28/01/2010

External links

- AAP Recommendations on Vitamin D Supplementation

- Dr. Susan Ott's website on osteomalacia

- Dictionary.com - Osteomalacia

- Fluoride & Osteomalacia

- History of Vitamin D and the battle against Rickets

- Rickets vs. abuse: a national and international epidemic

- 00906 at CHORUS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||