Victoria of the United Kingdom

| Victoria | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Photograph by Alexander Bassano, 1882 | |

|

|

|

| Reign | 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901 |

| Coronation | 28 June 1838 |

| Predecessor | William IV |

| Successor | Edward VII |

| Prime Ministers | See list |

| Consort | Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Issue | |

| Victoria, German Empress Edward VII of the United Kingdom Alice, Grand Duchess of Hesse Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Princess Helena, Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany Princess Beatrice, Princess Henry of Battenberg |

|

| Full name | |

| Alexandrina Victoria | |

| House | House of Hanover |

| Father | Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn |

| Mother | Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld |

| Born | 24 May 1819 Kensington Palace, London |

| Died | 22 January 1901 (aged 81) Osborne House, Isle of Wight |

| Burial | 2 February 1901 Frogmore, Windsor |

| Signature |  |

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was the Queen regnant of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837, and the first Empress of India of the British Raj from 1 May 1876, until her death. At 63 years and 7 months, her reign as the Queen lasted longer than that of any other British monarch, and is the longest of any female monarch in history. Her reign is known as the Victorian era, and was a period of industrial, cultural, political, scientific, and military progress within the United Kingdom.

Victoria was of mostly German descent; she was the daughter of the fourth son of George III, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn. Both the Duke of Kent and George III died a year after her birth, and she inherited the throne at the age of 18 after her father's three elder brothers died without surviving legitimate issue. She ascended the throne when the United Kingdom was already an established constitutional monarchy, in which the king or queen held relatively few direct political powers and exercised influence by the prime minister's advice; but she became the iconic symbol of the nation and empire. She had strict standards of personal morality. Her reign was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire, which reached its zenith and became the foremost global power.

Her 9 children and 42 grandchildren married into royal families across the continent, tying them together and earning her the nickname "the grandmother of Europe".[1] She was the last British monarch of the House of Hanover; her son King Edward VII belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Contents |

Heiress to the throne

Victoria was born at 4.15 a.m. on 24 May 1819 at Kensington Palace in London.[2] She was the only child of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, and his wife, Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. The Duke of Kent was the fourth son of the reigning King of the United Kingdom, George III. Victoria was christened privately by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners-Sutton, on 24 June 1819 in the Cupola Room at Kensington Palace. Her godparents were Emperor Alexander I of Russia (for whom her uncle the Duke of York stood proxy), her uncle the Prince Regent (later George IV), her aunt Queen Charlotte of Württemberg (whose sister The Princess Augusta Sophia stood in proxy) and her maternal grandmother the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (for whom Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh, the infant princess's aunt, stood proxy). On the instructions of the Prince Regent, she was named Alexandrina, after Emperor Alexander I, and Victoria after her mother.[3]

Painting by Stephen Poyntz Denning, 1823

The King's three eldest sons, the Prince Regent, the Duke of York, and the Duke of Clarence (later William IV), had no surviving legitimate children, which placed Victoria fifth in the line of succession after her uncles and father. Her grandfather and father died in 1820, and the Duke of York died in 1827. On the death of her uncle George IV in 1830, she became heiress presumptive to her surviving uncle, William IV. Parliament passed the Regency Act 1830, to make special provision for a child monarch if William died while Victoria was still a minor. Victoria's mother, the Duchess of Kent, would act as sole Regent during the Queen's minority, without a council to limit her powers.[4] King William distrusted the Duchess's capacity to be Regent, and declared in her presence that he wanted to live until Victoria's 18th birthday, so that a regency could be avoided.[1]

Victoria later described her childhood as "rather melancholy."[5] Victoria's mother was extremely protective of the princess, who was raised in near isolation under the so called "Kensington System", an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by The Duchess and her comptroller and supposed lover, Sir John Conroy, to prevent the princess from ever meeting people whom they deemed undesirable, and to render her weak and utterly dependent upon them.[6] She was not allowed to interact with other children. Her main companion was her King Charles spaniel, Dash, and she was required to share a bedroom with her mother every night until she became queen.[6] As a teenager, Victoria resisted their threats and rejected their attempts to make Conroy her personal secretary. Once queen, she immediately banned Conroy from her quarters (though she could not remove him from her mother's household) and consigned her mother to a distant corner of the palace, often refusing to see her.[6]

The Duchess was scandalised by her brothers-in-law's numerous mistresses and bastard children, and the widespread public contempt for the royal family that resulted; she taught her daughter that she must avoid any hint of sexual impropriety, which has been proposed as having prompted the emergence of Victorian morality.[6]

Victoria's governess, Baroness Lehzen from Hanover, was a formative influence for Victoria and continued to run Victoria's household after she ascended to the throne. Victoria's close relationship with Baroness Lehzen came to an end some time after the queen married Prince Albert, who found Lehzen incompetent for her authority in the household, to the point of threatening the safety and health of their first child.

Early reign

Accession

On 24 May 1837 Victoria turned 18, and a second British Regency was avoided. On 20 June 1837, William IV died from heart failure at the age of 71,[7] and Victoria became Queen of the United Kingdom.[8] In her diary she wrote, "I was awoke at 6 o'clock by Mamma ...who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing gown) alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past 2 this morning, and consequently that I am Queen..."[7] Drafts of all the official documents (proclamation, oaths of allegiance, etc.) prepared on the first day of her reign described her as Queen Alexandrina Victoria, but at her first Privy Council meeting she signed the register as Victoria; thus, although she was expected to reign as Alexandrina Victoria, the first name was withdrawn at her own wish.[9] Her coronation took place on 28 June 1838, and she became the first monarch to take up residence at Buckingham Palace.[10]

Under Salic law, however, no woman could be monarch of Hanover, a realm which had shared a monarch with Britain since 1714. Hanover passed to her uncle, the Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale, who became King Ernest Augustus I. (He was the fifth son and eighth child of George III.) As the young queen was as yet unmarried and childless, Ernest Augustus also remained the heir presumptive to the throne of the United Kingdom until Victoria's first child was born in 1840.[11]

At the time of her accession, the government was controlled by the Whig Party. The Whig Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, at once became a powerful influence in the life of the politically inexperienced Queen, who relied on him for advice—some even referred to Victoria as "Mrs. Melbourne".[13] However, the Melbourne ministry would not stay in power for long; it was growing unpopular and, moreover, faced considerable difficulty in governing the British colonies, especially during the Rebellions of 1837. In 1839, Lord Melbourne resigned after the Radicals and the Tories (both of whom Victoria detested at that time) joined together to block a Bill before the House of Commons that would have suspended the Constitution of Jamaica.[14]

Victoria's principal advisor was her uncle King Leopold I of Belgium (her mother's brother, and the widower of Victoria's cousin, Princess Charlotte).[13]

The Queen then commissioned Sir Robert Peel, a Tory, to form a new ministry, but was faced with a debacle known as the Bedchamber Crisis. At the time, it was customary for appointments to the Royal Household to be based on the patronage system (that is, for the Prime Minister to appoint members of the Royal Household on the basis of their party loyalties). Many of the Queen's Ladies of the Bedchamber were wives of Whigs, but Peel expected to replace them with wives of Tories. Victoria strongly objected to the removal of these ladies, whom she regarded as close friends rather than as members of a ceremonial institution. Peel felt that he could not govern under the restrictions imposed by the Queen, and consequently resigned his commission, allowing Melbourne to return to office.[13]

Marriage

Princess Victoria first met her future husband, her first cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, when she was just seventeen in 1836. Some authors have written that she initially found Albert to be rather dull.[15] However according to her diary, she enjoyed his company from the beginning. After the visit she wrote, "[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful."[16] She also wrote to her maternal uncle Leopold I of Belgium to thank him "for the prospect of great happiness you have contributed to give me, in the person of dear Albert ... He possesses every quality that could be desired to render me perfectly happy."[17] Prince Albert's father was one of her mother's brothers, Ernest, who approved the match. However at seventeen, the Princess Victoria, though interested in Albert, was not yet ready to marry.

Victoria came to the throne aged just eighteen on 20 June 1837. Though queen, as an unmarried young woman Victoria was nonetheless required to live with her mother, with whom she was quite angry over the Kensington System. Victoria gave her mother a remote apartment in Buckingham Palace and usually refused to meet her. Lord Melbourne advised Victoria to marry in order to be free of her mother. Her letters of the time show interest in Albert's education for the future role he would have to play as her husband, although she resisted attempts to rush her into marriage.[18]

Though initially Victoria was quite popular, her reputation suffered somewhat in an 1839 court intrigue when one of her mother's ladies-in-waiting, Lady Flora Hastings, developed an abdominal tumour that resulted in her death in July 1839. Lady Flora at first refused to submit to a physical examination by a doctor, and her abdominal growth was widely rumoured to be an out-of-wedlock pregnancy by Sir John Conroy, who was long rumoured to be the lover of Victoria's mother. Victoria hated Conroy for his role in constructing the Kensington System that had rendered her childhood so unhappy, and believed the rumours. Lady Flora eventually submitted to an examination and was found to have a terminal tumour. When she died several months later, Conroy and Lady Flora's brother organised a press campaign accusing the Queen of spreading false and disgraceful insults about Lady Flora.

Victoria continued to praise Albert following his second visit in October 1839 after she had become Queen, when she wrote of him: "...dear Albert... He is so sensible, so kind, and so good, and so amiable too. He has besides, the most pleasing and delightful exterior and appearance you can possibly see."[15] Albert and Victoria felt mutual affection and the Queen proposed to Albert just five days after he had arrived at Windsor on 15 October 1839.[19]

The Queen and Prince Albert were married on 10 February 1840, in the Chapel Royal of St. James's Palace, London. Albert became not only the Queen's companion, but an important political advisor, replacing Lord Melbourne as the dominant figure in the first half of her life following Melbourne's death.[20] Victoria's mother was evicted from the palace, and Victoria rarely visited her.

During Victoria's first pregnancy, eighteen-year-old Edward Oxford attempted to assassinate the Queen while she was riding in a carriage with Prince Albert in London.[8] Oxford fired twice, but both bullets missed. He was tried for high treason, but was acquitted on the grounds of insanity.[21] The first of the royal couple's nine children, named Victoria, was born on 21 November 1840.[22]

Further attempts to assassinate Queen Victoria occurred between May and July 1842. First, on 29 May at St. James's Park, John Francis fired a pistol at the Queen while she was in a carriage,[8] but was immediately seized by Police Constable William Trounce. Francis was convicted of high treason. The death sentence was commuted to transportation for life. Then, on 3 July, just days after Francis's sentence was commuted, another boy, John William Bean,[8] attempted to shoot the Queen. Prince Albert felt that the attempts were encouraged by Oxford's acquittal in 1840. Although his gun was loaded only with paper and tobacco, his crime was still punishable by death. Feeling that such a penalty would be too harsh, Prince Albert encouraged Parliament to pass the Treason Act 1842. Under the new law, an assault with a dangerous weapon in the monarch's presence with the intent of alarming her was made punishable by seven years' imprisonment and flogging.[23] Bean was thus sentenced to 18 months' imprisonment; however, neither he, nor any person who violated the act in the future, was flogged.[24]

During the same summer as these two assassination attempts, Victoria made her first journey by train, travelling from Slough railway station (near Windsor Castle) to Bishop's Bridge, near Paddington (in London), on 13 June 1842 in the special royal carriage provided by the Great Western Railway. Accompanying her were her husband and the engineer of the Great Western line, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The Queen and the Prince Consort both complained the train was going too fast at 20 mph (30 km/h), fearing the train would derail.[8]

Early Victorian politics and further assassination attempts

Peel's ministry soon faced a crisis involving the repeal of the Corn Laws. Many Tories—by then known also as Conservatives—were opposed to the repeal, but some Tories (the "Peelites") and most Whigs supported it. Peel resigned in 1846, after the repeal narrowly passed, and was replaced by Lord John Russell. Russell's ministry, though Whig, was not favoured by the Queen. Particularly offensive to Victoria was the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who often acted without consulting the Cabinet, the Prime Minister, or the Queen.[25]

In 1849, Victoria lodged a complaint with Lord John Russell, claiming that Palmerston had sent official dispatches to foreign leaders without her knowledge. She repeated her remonstrance in 1850, but to no avail. It was only in 1851 that Lord Palmerston was removed from office; he had on that occasion announced the British government's approval for President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's coup in France without prior consultation of the Prime Minister.[25]

| Victoria's British Prime Ministers | |

| Year | Prime Minister (party) |

| 1835 | Lord Melbourne (Whig) |

| 1841 | Sir Robert Peel (Conservative) |

| 1846 | Lord John Russell (Whig) |

| 1852 (Feb.) | Lord Derby (Cons.) |

| 1852 (Dec.) | Lord Aberdeen (Peelite) |

| 1855 | Lord Palmerston (Liberal) |

| 1858 | Derby (C.) |

| 1859 | Palmerston (L.) |

| 1865 | Russell (L.) |

| 1866 | Derby (C.) |

| 1868 (Feb.) | Benjamin Disraeli (Cons.) |

| 1868 (Dec.) | William Ewart Gladstone (Lib.) |

| 1874 | Disraeli (C.) |

| 1880 | Gladstone (L.) |

| 1885 | Lord Salisbury (Cons.) |

| 1886 (Feb.) | Gladstone (L.) |

| 1886 (July) | Salisbury (C.) |

| 1892 | Gladstone (L.) |

| 1894 | Lord Rosebery (Lib.) |

| 1895 | Salisbury (C.) |

| Also see List of British Prime Ministers and, for her British and Imperial premiers, List of Prime Ministers of Queen Victoria |

|

The period during which Russell was Prime Minister also proved personally distressing to Queen Victoria. In 1849, an unemployed and disgruntled Irishman named William Hamilton attempted to alarm the Queen by firing a powder-filled pistol as her carriage passed along Constitution Hill, London. Hamilton was charged under the 1842 act; he pleaded guilty and received the maximum sentence of seven years of penal transportation.[26]

In 1850, the Queen did sustain injury when she was assaulted by a possibly insane ex-Army officer, Robert Pate. As Victoria was riding in a carriage, Pate struck her with his cane, crushing her bonnet and bruising her. Pate was later tried; he failed to prove his insanity, and received the same sentence as Hamilton.[25]

Ireland

The young Queen Victoria fell in love with Ireland, choosing to holiday in Killarney in Kerry. Her love of the country was matched by initial Irish warmth towards the young Queen. In 1845, Ireland was hit by a potato blight that over four years cost the lives of over a million Irish people and saw the emigration of another million.[27] In response to what came to be called the Great Famine (in Irish, An Gorta Mór), the Queen personally donated £2,000 (2,000 pounds sterling) to the Irish people.[28] However, when Sultan Abdülmecid I of the Ottoman Empire declared that he would send £10,000 in aid, Queen Victoria requested that the Sultan send only £1,000, because she had sent only £2,000. The Sultan sent the £1,000 but also secretly sent three ships full of food. British courts tried to block the ships, but the food arrived at Drogheda harbour and was left there by Ottoman sailors. However, myths were generated towards the end of the 19th century that she had donated a maximum of £5 in aid to the Irish, and on the same day also gave £5 to Battersea Dog Shelter. This was false, as she in fact contributed £2,000, substantially more than many Irish Catholic Bishops, one of whom donated £1,000 to a charity for the hungry and £10,000 to a University project.[29]

Additionally, the policies of her prime minister, Lord John Russell, were often blamed for exacerbating the severity of the famine, which adversely affected the Queen's popularity in Ireland. However Victoria was a strong supporter of the Irish; she supported the Maynooth Grant and made a point, on visiting Ireland, of visiting the seminary.[30]

Victoria's first official visit to Ireland, in 1849, was specifically arranged by Lord Clarendon, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland—the head of the British administration—to try to both draw attention from the famine and alert British politicians through the Queen's presence to the seriousness of the crisis in Ireland. Despite the negative impact of the famine on the Queen's popularity she remained popular enough for many Irish nationalists at party meetings to finish by singing "God Save the Queen".[31] She became known in Ireland as "The Famine Queen",[32] and was much vilified then, as now.[33] In 1853 she visited the Great Industrial Exhibition which was the biggest international event held to date in Ireland. Over one million attended and Victoria knighted the architect of the exhibition, John Benson.[34]

By the 1870s and 1880s the monarchy's appeal in Ireland had diminished substantially, partly because Victoria refused to visit Ireland in protest at the Dublin Corporation's decision not to congratulate her son, the Prince of Wales on both his marriage to Princess Alexandra of Denmark and on the birth of the royal couple's oldest son, Prince Albert Victor.[30] Queen Victoria had also felt deeply hurt after Dublin Corporation had returned a bust of her beloved late husband Albert, which she sent as a gift to the people of Dublin. In addition, she had felt hurt by the indignation at the suggestion to place a statue of Albert on St. Stephen's Green in Dublin, and to rename it 'Albert Green'. It has been theorised that these perceived 'insults' to her beloved Albert's memory hardened her views of the Irish people.[35]

Victoria refused repeated pressure from a number of prime ministers, lords lieutenant and even members of the Royal Family, to establish a royal residence in Ireland.[31] Lord Midleton, the former head of the Irish unionist party, writing in his memoirs of 1930 Ireland: Dupe or Heroine?, described this decision as having proved disastrous to the monarchy and the union.[36]

The Queen paid her last visit to Ireland in 1900, when she came to appeal to Irishmen to join the British Army and fight in the Second Boer War. Nationalist opposition to her visit was spearheaded by Arthur Griffith, who established an organisation called Cumann na nGaedhael to unite the opposition. Five years later Griffith used the contacts established in his campaign against the Queen's visit to form a new political movement, Sinn Féin,[31] which ultimately brought about the establishment of the Irish Free State.

Empress of India

After the Mughal Emperor was deposed by the British East India Company, and after the company itself was dissolved, the title "Empress of India" was taken by Victoria from 1 May 1876, and proclaimed at the Delhi Durbar of 1877. The title was created nineteen years after the formal incorporation into the British Empire of Britain's possessions and protectorates on the Indian subcontinent. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli is usually credited with creating the title for her.[37] Victoria began learning Hindi and Punjabi in 1867.

Widowhood

The Prince Consort died of typhoid fever on 14 December 1861, due to the primitive sanitary conditions at Windsor Castle. His death devastated Victoria, who was still affected by the death of her mother in March of that year.[38] She entered a state of mourning and wore black for the remainder of her life. She avoided public appearances, and rarely set foot in London in the following years. Her seclusion earned her the name "Widow of Windsor." She blamed her son Edward, the Prince of Wales, for his father's death, since news of the Prince's poor conduct had come to his father in November, leading Prince Albert to travel to Cambridge to confront his son.[38]

Victoria's self-imposed isolation from the public greatly diminished the popularity of the monarchy, and even encouraged the growth of the republican movement. She did undertake her official government duties, yet she also chose to remain secluded in her royal residences—Balmoral Castle in Scotland, Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, and Windsor Castle.[38]

As time went by, Victoria began to rely increasingly on a manservant from Scotland, John Brown.[38] A romantic connection and even a secret marriage have been alleged, but both charges are generally discredited. However, when Victoria's remains were laid in the coffin, two sets of mementos were placed with her, at her request. By her side was placed one of Albert's dressing gowns, while in her left hand was placed a piece of Brown's hair, along with a picture of him. It was learned in 2008 that Victoria's body wore the wedding ring of John Brown's mother, placed on her hand after her death.[39] Rumours of an affair and marriage earned Victoria the nickname "Mrs Brown".[38] The story of their relationship was the subject of the 1997 movie Mrs. Brown.[40]

Later years

Golden Jubilee and an assassination attempt

In 1887, the British Empire celebrated Victoria's Golden Jubilee. Victoria marked the fiftieth anniversary of her accession on 20 June with a banquet to which 50 European kings and princes were invited. Although she could not have been aware of it, there was a plan—ostensibly by Irish anarchists—to blow up Westminster Abbey. This assassination attempt, when it was discovered, became known as the Jubilee Plot. On the next day, she participated in a procession that, in the words of Mark Twain, "stretched to the limit of sight in both directions". By this time, Victoria was once again an extremely popular monarch.[25]

Diamond Jubilee

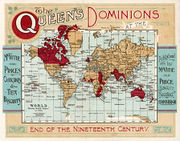

On 25 September 1896, Victoria surpassed George III as the longest-reigning monarch in English, Scottish, and British history. The Queen requested all special public celebrations of the event to be delayed until 1897, to coincide with her Diamond Jubilee. The Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, proposed that the Diamond Jubilee be made a festival of the British Empire.[31]

The Prime Ministers of all the self-governing dominions and colonies were invited. The Queen's Diamond Jubilee procession included troops from every British colony and dominion, together with soldiers sent by Indian princes and chiefs as a mark of respect to Victoria, the Empress of India. The Diamond Jubilee celebration was an occasion marked by great outpourings of affection for the septuagenarian Queen. A service of thanksgiving was held outside St. Paul's Cathedral. Queen Victoria sat in her carriage throughout the service; she wore her usual black mourning dress trimmed with white lace.[13] Many trees were planted to celebrate the Jubilee, including 60 oak trees at Henley-on-Thames in the shape of a Victoria Cross.[41][42] The VC was introduced on 29 January 1856 by Queen Victoria to reward acts of valour during the Crimean War, and its modern Commonwealth variants remain to this day the highest British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and Commonwealth awards for bravery.

Death and succession

Following a custom she maintained throughout her widowhood, Victoria spent the Christmas of 1900 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. She died there from a cerebral haemorrhage on Tuesday 22 January 1901 at half past six in the evening,[43][44] at the age of 81. At her deathbed she was attended by her son, the future King, and her eldest grandson, German Emperor Wilhelm II. As she had wished, her own sons lifted her into the coffin. She was dressed in a white dress and her wedding veil, and the coffin was draped with the Royal Standard that had been flying at Osborne House; it was later given by Victoria's grandson, George V, to Victoria College at the University of Toronto.[45] Her funeral was held on Saturday 2 February, and after two days of lying-in-state, she was interred beside Prince Albert in Frogmore Mausoleum at Windsor Great Park. Since Victoria disliked black funerals, London was instead festooned in purple and white. When she was laid to rest at the mausoleum, it began to snow.[46]

Flags in the United States were lowered to half-mast in her honour by order of President William McKinley, a tribute never before offered to a foreign monarch at the time and one which was repaid by Britain when McKinley was assassinated later that year. Victoria had reigned for a total of 63 years, seven months and two days—the longest of any British monarch—and surpassed her grandfather, George III, as the longest-lived monarch (since surpassed by Elizabeth II) only three days before her death.[47][48]

Victoria's death brought an end to the rule of the House of Hanover in the United Kingdom. Her husband belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and her son and heir Edward VII was the first British monarch of this new house.[15] Later, in 1917, her grandson King George V changed the house name from Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the (currently serving) House of Windsor.

Victoria outlived 3 of her 9 children, and came within seven months of outliving a fourth (her eldest daughter, Victoria, who died of spinal cancer in August 1901 aged 60). She outlived 11 of her 42 grandchildren (3 were stillborn, 6 died as children, and 2 as adults).[49]

Legacy

Within Britain

Queen Victoria's reign marked the gradual establishment of a modern constitutional monarchy. A series of legal reforms saw the House of Commons' power increase, at the expense of the House of Lords and the monarchy, with the monarch's role becoming gradually more symbolic. Since Victoria's reign the monarch has had only, in Walter Bagehot's words, "the right to be consulted, the right to advise, and the right to warn".[31]

As Victoria's monarchy became more symbolic than political, it placed a strong emphasis on morality and family values, in contrast to the sexual, financial and personal scandals that had been associated with previous members of the House of Hanover and which had discredited the monarchy. Victoria's reign created for Britain the concept of the "family monarchy" with which the burgeoning middle classes could identify.[15]

The sudden appearance of haemophilia in Victoria's descendants has led to suggestions that her true father was not the Duke of Kent but a haemophiliac. Victoria was the first known carrier of haemophilia in the royal line. Since no haemophiliacs were among her known ancestors, hers was either an instance of spontaneous mutation, or she was actually illegitimate, her father an unidentified haemophiliac male rather than the Duke of Kent.[50] Spontaneous mutations account for about 30% of all haemophilia A[51], and haemophilia B cases.[52] There is no documentary evidence of a haemophiliac man in connection with Victoria's mother, and as male carriers always suffer the disease, even if such a man had existed he would have been seriously ill.[53]

Evidence indicates Victoria passed the gene on to two of her five daughters: Princess Alice and Princess Beatrice. Her son, Prince Leopold, was affected by the disease. The most famous haemophilia victims among her descendants were her great-grandson, Alexei, Tsarevich of Russia, and Alfonso, Prince of Asturias and Infante Gonzalo of Spain, the eldest and youngest sons of King Alfonso XIII of Spain and Queen Victoria Eugenie (Victoria's granddaughter).[54]

Queen Victoria experienced unpopularity during the first years of her widowhood, but afterwards became extremely well-liked during the 1880s and 1890s. In 2002, the BBC conducted a poll regarding the 100 Greatest Britons; Victoria attained the eighteenth place.[55]

The design of the Queen's head on the first postage stamp was based upon the 1837 Wyon City medal engraved by a famous coin engraver William Wyon. The design of Queen Victoria's head is based on a sitting when she was a princess aged 15.[56] Victoria also started the tradition that a bride wears a white dress to her wedding. Before Victoria's wedding a bride would wear her best dress of no particular colour.[57]

The Victoria Memorial outside Buckingham Palace—which was erected as part of the remodelling of the façade of the Palace a decade after her death.

Several places in the world have been named after Victoria.

International Legacy

Internationally Victoria was a major figure, not just in image or in terms of Britain's influence through the empire, but also because of family links throughout Europe's royal families, earning her the affectionate nickname "the grandmother of Europe". Queen Victoria remains the most commemorated British monarch in history, with statues to her erected throughout the former territories of the British Empire. For example, three of the main monarchs with countries involved in the First World War on the opposing side were either grandchildren of Victoria's or married to a grandchild of hers. Eight of Victoria's nine children married members of European royal families, and the other, Princess Louise, married the Marquess of Lorne, a future Governor-General of Canada.[58]

Victoria and Albert had 42 grandchildren and their current descendants number into the hundreds. As of 2009, the European monarchs and former monarchs descended from Victoria are: Queen Elizabeth II (as well as her husband), King Harald V of Norway, King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, King Juan Carlos I of Spain (as well as his wife), and the deposed kings Constantine II of Greece (as well as his wife) and Michael of Romania. The pretenders to the thrones of Serbia, Russia, Prussia and Germany, Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Hanover, Hesse, Baden and France (Legitimist) are also descendants.[59]

Around the world, places and memorials are dedicated to Victoria, especially in the Commonwealth nations.

The capital of the Seychelles, Africa's largest lake, and Victoria Falls are all named after Victoria.[31]

Victoria, or Città Vittoria, is the capital of Gozo, an island of the Maltese archipelago in the Mediterranean. Victoria is the name given in 1887 by the British government on the occasion of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, at the request of the Bishop of Malta, Mons. Sir Pietro Pace. However Gozitans still often refer to it by its old name, Rabat.

The prominent Victoria Memorial in Kolkata (Calcutta), India—to the obscure: in the town of Cape Coast, Ghana, a bust of the Queen presides, rather forlornly, over a small park where goats graze around her. Many institutions, thoroughfares, parks, and structures bear her name.[15]

Similarly in Wellington, the capital of New Zealand a statue toward the harbour from the centre of Kent and Cambridge Terraces.

In Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, an imposing building named Victoria Memorial Hall, was built in homage to the queen. At Bangalore, India, the statue of the Queen stands at the beginning of MG Road, one of the city's major roads.[60]

In Hong Kong, a statue of Queen Victoria is located on the east side of Victoria Park in Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Island. The statue once sat in Statue Square in Central but was removed and sent to Tokyo to be destroyed at the time of Japanese occupation of the territory, during World War II. With Japan's defeat and subsequent retreat in 1945, The United Kingdom recovered Hong Kong, and the statue was retrieved and placed in the park. There is also a Queen Victoria Statue in the heart of Valletta, Malta's capital.[61]

In Pietermaritzburg, capital of the South African province of KwaZulu Natal, formerly the British colony of Natal before formation of the Union of South Africa, there is a statue of Victoria in front of the provincial legislature building, the former parliament building of the colony of Natal. There is also a statue of Queen Victoria in front of the South African Parliament.

Queen Victoria invited Martha Ann Ricks, on behalf of Liberian Ambassador Edward Wilmot Blyden, to Windsor Castle on 16 July 1892. Martha Ricks, a former slave from Tennessee, had saved her pennies for more than fifty years, to afford the voyage from Liberia to England to personally thank the Queen for sending the British navy to patrol the coast of West Africa to prevent slavers from exporting Africans for the slave trade. Martha Ricks shook hands with the Queen and presented her with a Coffee Tree quilt, which Queen Victoria later sent to the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition for display. A mystery remains as to where the Coffee Tree quilt is today. The Royal Victoria Teaching Hospital in The Gambia is also named after the Queen. [62]

Australia

Queen Victoria was prominent in the Australian colonies. Two Australian States (Victoria and Queensland) were named after her. Australia went through a period of rapid growth and great prosperity during her reign due primarily to the Australian gold rushes.

Most of the large capital cities that prospered during the Victorian era feature prominent statues of Queen Victoria. Sydney, the capital city of New South Wales has several. There is one statue (re-sited from the forecourt of the Irish Parliament building in Dublin) dominating the southern entrance to the Queen Victoria Building that was named in her honour in 1898. Another Sydney statue of Queen Victoria stands in the forecourt of the Federal Court of Australia building on Macquarie Street, looking across the road to a statue of her husband, inscribed "Albert the Good". In Melbourne, the capital of Victoria, the Queen Victoria Gardens named after her also features a large memorial statue in marble and granite. In Perth, capital city of Western Australia a marble statue stands in King's Park overlooking the city. In Adelaide, capital city of the state of South Australia, the Queen Victoria Square, named after her also has a large statue of her;[63]. In Brisbane, capital city of the state of Queensland, there is a statue of her in Queens Square, also named for her;[64]. Ballarat, a boomtown in Victoria has a statue of Queen Victoria in the main street directly opposite its town hall.

During her reign, Victoria appeared on several Australian postage stamps including those of the colonies of Victoria one penny (1850); New South Wales two pence (1851); South Australia two pence (1855); Van Diemens Land (Tasmania) two pence (1855); Queensland two pence (1860). Victoria has been commemorated on Australian stamps of 1950, 1953, 1955, 1960, 1999, 2000 as well as in stamps for the Australia territories Christmas Island (1958) and Cocos (Keeling) Islands (1982).

There are numerous Australian roads named after Queen Victoria including numerous Victoria Streets in towns and cities across Australia, perhaps the most notable being Melbourne's Victoria Parade. Queen Victoria Street in Bexley and Drummoyne in Sydney, North Fremantle the town of Leonora in Western Australia and Newington, a suburb of Ballarat.

Canada

Queen Victoria was prominent in Canada and the capitals of British Columbia (Victoria) and Saskatchewan (Regina) are named for Queen Victoria.

Victoria Day is a Canadian statutory holiday celebrated on the last Monday before or on 24 May in honour of both Queen Victoria's birthday and the current reigning Canadian Sovereign's birthday. While Victoria Day is often thought of as a purely Canadian event, it is also celebrated in some parts of Scotland, particularly in Edinburgh and Dundee, where it is also a public holiday.[65]

Queen Victoria has featured on Canadian stamps, including the Nova Scotia 1/2 cent stamp (1860) and the Canadian 20 cent stamp (1893).

Statues erected to Victoria are common in Canada, where her reign was coterminous with the confederation of the country and the creation of several new provinces. A bas-relief image of Victoria is on the wall of the entrance to the Canadian Parliament, and her statue is in the Parliamentary library as well as on the grounds.[66]

Titles, styles, coat of arms and cypher

| Royal styles of Victoria of the United Kingdom |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | Her Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

| Alternative style | Ma'am |

Titles and styles

- 24 May 1819 – 20 June 1837: Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent[67]

- 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901: Her Majesty The Queen[67]

- 1 May 1876 – 22 January 1901: Her Imperial Majesty The Queen-Empress[67]

As the male-line granddaughter of a King of Hanover, Victoria also bore the titles of Princess of Hanover and Duchess of Brunswick and Lunenburg. In addition, she held the titles of Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Duchess in Saxony etc. as the wife of Prince Albert.[67]

At the end of her reign, the Queen's full style and title were:

| “ | Her Majesty Victoria, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland Queen, Defender of the Faith, Empress of India.[68] | ” |

Coat of arms

As Victoria could not succeed to the throne of Hanover, the royal arms since 1837 have no longer carried Hanoverian symbols but just four quarters representing England, Scotland and Ireland. Victoria's arms have been borne by all of her successors on the throne, including the present Queen.

Outside Scotland, the shield of Victoria's coat of arms—also used on her Royal Standard—was:

Quarterly:

I and IV, Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale Or [ — for England] ;

II, Or, a lion rampant within a double tressure flory-counter-flory Gules [ — for Scotland] ;

III, Azure, a harp Or stringed Argent [ — for Ireland].

[In heraldic blazon, Or is gold (or yellow), Gules is red, Azure is blue, and Argent is silver (or white).]

Within Scotland, the first and fourth quarters were taken by the Scottish lion, and the second by the English lions. The Lion and the Unicorn who supported the shield also differed between Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom.[69][70]

Royal Cypher

Victoria's Royal Cypher was the first to be used on a postbox. The letters are VR interlaced, standing for "Victoria Regina". Victoria eventually used the cypher VRI ("Victoria Regina Imperatrix") when she became Empress, but this never appeared on postboxes. Victoria's cypher was the only one to appear on postboxes without a crown above it.[70]

|

Ancestors and descendants

Ancestors and cousins

Both Victoria and Albert were grandchildren of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, whose son Duke Ernest was Prince Albert's father and whose daughter Princess Victoria was Queen Victoria's mother.

[Another son of Duke Francis was Leopold I, the first King of the Belgians (reigned 1831–1865), who, besides being Victoria's uncle, was father to King Leopold II (1865–1909) and to the Mexican Empress Carlotta (1864–1867).]

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Children

| Portrait of Queen Victoria's family in 1846 by Franz Xaver Winterhalter |

|---|

|

| Picture | Name | Birth | Death | Spouse (dates of birth & death) and children[68][71] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The Princess Victoria, Princess Royal |

21 November 1840 |

5 August 1901 |

Married 1858 (25 January), Prussian Crown Prince Frederick, later Frederick III, German Emperor and King of Prussia (1831–1888); 4 sons, 4 daughters (including German Emperor William II and Sophia of Prussia, Queen of the Greeks) |

|

The Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII |

9 November 1841 |

6 May 1910 |

Married 1863 (10 March), Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844–1925); 3 sons, 3 daughters (including King George V and Maud of Wales, Queen of Norway) |

|

The Princess Alice | 25 April 1843 |

14 December 1878 |

Married 1862 (1 July), Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine (1837–1892); 2 sons, 5 daughters (including Alexandra, the last Empress of All the Russias) |

|

The Prince Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Duke of Edinburgh; Admiral of the Fleet |

6 August 1844 |

31 July 1900 |

Married 1874 (23 January), Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia (1853–1920); 2 sons (1 still-born), 4 daughters (including Marie of Edinburgh, Queen of Romania) |

|

The Princess Helena | 25 May 1846 |

9 June 1923 |

Married 1866 (5 July), Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg (1831–1917); 4 sons (1 still-born), 2 daughters |

|

The Princess Louise | 18 March 1848 |

3 December 1939 |

Married 1871 (21 March), John Douglas Sutherland Campbell (1845–1914), Marquess of Lorne, later 9th Duke of Argyll, also Governor-General of Canada (1878–83); no issue |

|

The Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn; Field Marshal, Governor General of Canada (1911–1916) |

1 May 1850 |

16 January 1942 |

Married 1879 (13 March), Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia (1860–1917); 1 son, 2 daughters |

.jpg) |

The Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany |

7 April 1853 |

28 March 1884 |

Married 1882 (27 April), Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont (1861–1922); 1 son, 1 daughter |

|

The Princess Beatrice | 14 April 1857[72] |

26 October 1944 |

Married 1885 (23 July), Prince Henry of Battenberg (1858–1896); 3 sons, 1 daughter (including Victoria Eugenie, Queen of Spain) |

See also

| British Royalty |

|---|

| House of Hanover |

.svg.png) |

| George III |

| Grandchildren |

| Charlotte, Princess Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld |

| Princess Elizabeth of Clarence |

| Victoria |

| George V, King of Hanover |

| George, Duke of Cambridge |

| Augusta, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck |

| Victoria |

- Cultural depictions of Victoria of the United Kingdom

- List of coupled cousins

- Royal descendants of Queen Victoria and King Christian IX

- Small diamond crown of Queen Victoria

- Victoria and Albert Museum

- Victorian era

- Victorian morality

- Abdul Karim, Queen Victoria's Munshi

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carolly Erickson (1997). Her Little Majesty: The Life of Queen Victoria. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-3657-2.

- ↑ Woodham-Smith, vol. 1, p. 29

- ↑ Woodham-Smith, vol. 1, pp. 34–35

- ↑ Woodham-Smith, vol. 1, p. 81

- ↑ Mike Mahoney. "Queen Victoria". Englishmonarchs.co.uk. http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/hanover_6.htm. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Lacey, Robert (2006). Great Tales from English History, Volume 3. London: Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 133–136. ISBN 0-316-11459-6.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Giles St. Aubyn (1992). Queen Victoria. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 55–60. ISBN 978-0340571095. OCLC 27171944.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Giles St. Aubyn (1992). Queen Victoria. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 161–165. ISBN 978-0340571095. OCLC 27171944.

- ↑ Ernest Llewellyn Woodward (1962). The age of reform, 1815–1870. Oxford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0198217110.

- ↑ "Buckingham Palace". The Royal Family. http://www.royal.gov.uk/output/Page555.asp. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ Jerrold M. Packard (1999). Victoria's Daughters. St. Martin's Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0312244965. OCLC 43559899.

- ↑ Queen Victoria and the Princess Royal, Royal Collection, http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/eGallery/object.asp?searchText=2931317%2Ec&x=5&y=15&object=2931317c&row=0&detail=about, retrieved 30 July 2010

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Christopher Hibbert (2001). Victoria: A Biography. Da Capo Press. pp. 16–78. ISBN 978-0306810855. OCLC 48687442 191215627 48687442.

- ↑ "Lord Melbourne (1779–1848)". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/melbourne_lord.shtml. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Dorothy Marshall (1972). The Life and Times of Queen Victoria. Book Club Associates. pp. 16–154.

- ↑ Victoria quoted in Weintraub, Stanley (1997) Albert: Uncrowned King London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5756-9, p. 49

- ↑ Victoria quoted in Weintraub, Stanley (1997) Albert: Uncrowned King London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5756-9, p. 51

- ↑ Weintraub, Stanley (1997) Albert: Uncrowned King London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5756-9, p. 62

- ↑ Weintraub, Stanley (1997) Albert: Uncrowned King London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5756-9, pp. 77–81

- ↑ "Prince Albert (1819–1861)". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/albert_prince.shtml. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ↑ Michael Diamond (2003). Victorian sensation. Anthem Press. ISBN 1-84331-150-X. OCLC 57519212.

- ↑ "Empress Frederick: The Last Hope for a Liberal Germany?". The Historian. 22 September 1999. http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-515932_ITM. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ↑ "Treason Act 1842 (c.51) – Statute Law Database". Statutelaw.gov.uk. [16 July 1842]. http://www.statutelaw.gov.uk/content.aspx?activeTextDocId=1034300. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ↑ Steve Poole (2000). The Politics of Regicide in England, 1760–1850: Troublesome Subjects. Manchester University Press. pp. 199–203. ISBN 0719050359. OCLC 222735433 44915199 47352204 59575274 185769902 222735433 44915199 47352204 59575274.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Giles St. Aubyn (1992). Queen Victoria. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 9–27. ISBN 978-0340571095. OCLC 27171944.

- ↑ "Third Attack on American Presidents" (PDF). New York Times. 7 September 1901. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9B07E0DF1E39EF32A25754C0A96F9C946097D6CF&oref=slogin. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ↑ David Ross (2002). Ireland: History of a Nation. New Lanark: Geddes & Grosset. p. 268. ISBN 1842051644. OCLC 52945911.

- ↑ Pope Pius IX. "Multitext – Private Responses to the Famine". Multitext.ucc.ie. http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/Private_Responses_to_the_Famine3344361812. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ↑ Kenny M., 'Crown and Shamrock – love and hate between Ireland and the British Monarchy',New Island, 2009

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Victoria (queen of United Kingdom)". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/627603/Victoria. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Giles St. Aubyn (1992). Queen Victoria. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0340571095. OCLC 27171944.

- ↑ Maud Gonne's 1900 article upon Queen Victoria's visit to Ireland was entitled this

- ↑ "Famine Queen row in Irish port". BBC News. 15 April 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/2951395.stm. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ↑ Dublin 1853 Main Hall – A Treasury of World's Fair Art & Architecture

- ↑ Kenny M., 'Crown and Shamrock – love and hate between Ireland and the British Monarchy',(2009),New Island Press

- ↑ Midleton, William St. John Fremantle Brodrick Midleton, William St. John Fremantle Brodrick (1932). Ireland-dupe or Heroine. William Heinemann.

- ↑ "History of the Monarchy, Victoria". Royal.gov.uk. http://www.royal.gov.uk/output/Page118.asp. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 Dorothy Marshall (1972). The Life and Times of Queen Victoria. Book Club Associates.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria's sex life exposed (Royal Watch News)". Monsters and Critics.com. 30 May 2008. http://www.monstersandcritics.com/people/royalwatch/news/article_1408421.php/Queen_Victorias_sex_life_exposed.

- ↑ "Mrs. Brown (1997)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://uk.rottentomatoes.com/m/mrs_brown/. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ↑ "Special trees and woods – Henley Cross | The Chilterns AONB". Chilternsaonb.org. http://www.chilternsaonb.org/caring/stwp_site_details.asp?siteID=585&frommap=truein. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ↑ "Google Maps". http://maps.google.com/maps?f=q&source=s_q&hl=en&geocode=&q=Henley-on-Thames&sll=51.535552,-0.893841&sspn=0.018232,0.05652&ie=UTF8&hq=&hnear=Henley-on-Thames,+Bell+Street,+Henley-on-Thames,+Oxfordshire+RG9+2,+United+Kingdom&t=h&ll=51.551873,-0.913314&spn=0.005417,0.016512&z=17. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Calendar for year 1901". Gazzetes-Online.co.uk. http://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/index.html?year=1901&country=1. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ↑ "Supplement to The London Gazette". London Gazette. 23 January 1901. http://www.gazettes-online.co.uk/ViewPDF.aspx?pdf=27270. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ↑ Rynor, F. Michah (2001). "Royal Gems". UofT Magazine (Toronto: University of Toronto) (Winter 2001). http://www.magazine.utoronto.ca/looking-back/founding-of-victoria-college-royal-gems/. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ↑ Giles St. Aubyn (1992). Queen Victoria. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 600. ISBN 978-0340571095. OCLC 27171944.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alan (21 December 2007). "The record-breaking age of Elizabeth, longest-lived monarch to reign over us". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article3080583.ece. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ "History of the Monarchy > Hanoverians > Victoria". The Royal Family. http://www.royal.gov.uk/output/Page118.asp. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ↑ "Grieving a grown-up child". BBC News. 15 February 2002. http://news.google.co.uk/archivesearch/url?sa=t&source=archive&ct=res&cd=5-0&url=http%3A%2F%2Fnews.bbc.co.uk%2F1%2Flow%2Fuk%2F1820374.stm&ei=JzLNSJqkOpeC3QbNytRq&usg=AFQjCNGHVO8irqyKbf57waEJem-58ewkXg. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ DM Potts & WTW Potts, Queen Victoria's Gene, Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0750908688

- ↑ "Hemophilia A (Factor VIII Deficiency)". http://www.hemophilia.org/NHFWeb/MainPgs/MainNHF.aspx?menuid=179&contentid=45&rptname=bleeding. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "Hemophilia B (Factor IX)". http://www.hemophilia.org/NHFWeb/MainPgs/MainNHF.aspx?menuid=181&contentid=46&rptname=bleeding. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "In the Blood". Jones, Steve. In the Blood. BBC. 1996.

- ↑ Daniel L. Hartl, Elizabeth W. Jones (2005). Genetics. Jones & Bartlett. ISBN 9780763715113. OCLC 55044495.

- ↑ Wells, Matt (22 August 2002). "The 100 greatest Britons: lots of pop, not so much circumstance". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2002/aug/22/britishidentityandsociety.television. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ "A Royal Icon – The Machin Stamp". Postal Heritage. http://216.239.59.104/search?q=cache:ReXbbK72LRYJ:postalheritage.org.uk/exhibitions/icons/downloads/Teachers_notes_MachinStamp.pdf+Teachers+Notes+Machin+Stamp&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=uk&client=firefox-a. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ Newell, Claire (9 April 2006). "Here comes the scarlet bride". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article703537.ece. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ Martin J. Daunton, Bernhard Rieger (2001). Meanings of Modernity. Berg Publishers. ISBN 9781859734025. OCLC 238671662 45647912 46737764 186477900 238671662 45647912 46737764.

- ↑ Elizabeth Harman Pakenham Longford (1965). Queen Victoria: Born to Succeed. Harper & Row.

- ↑ "Striving for musical freedom". Deccan Herald. http://www.deccanherald.com/Content/Aug212008/metrothurs2008082085629.asp. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ "Statue of Queen Elizabeth in Valletta, Malta". Maltadailyphoto.blogspot.com. 8 March 2007. http://maltadailyphoto.blogspot.com/2007/03/statue-of-queen-elizabeth-in-valletta.html. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ Kyra E. Hicks (2006). Martha Ann's Quilt for Queen Victoria. Brown Books Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1933285597. OCLC 70866874.

- ↑ "Adelaide – Statues and Memorials". State Library South Australia. http://www.slsa.sa.gov.au/manning/adelaide/statues/statues.htm. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ "Valour of the visionary". The Australian. 21 July 2008. http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,24048837-16947,00.html. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ Hepburn, Bob (15 May 2008). "Let's get rid of Victoria Day". The Toronto Star. http://www.thestar.com/comment/article/425517. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ Taylor, Bill (17 May 2008). "Sun never sets on Queen Victoria statues". The Toronto Star. http://www.thestar.com/article/425461. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 67.3 Greg Taylor, Nicholas Economou (2006). The Constitution of Victoria. Federation Press. pp. 72–74. ISBN 9781862876125. OCLC 81948853.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Whitaker's Almanack, 1900, Facsimile Reprint 1999 (ISBN 0-11-702247-0), page 86

- ↑ Greg Taylor, Nicholas Economou (2006). The Constitution of Victoria. Federation Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781862876125. OCLC 81948853.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Stephen Patterson (1996). Royal Insignia. Merrell Holberton. ISBN 9781858940250. OCLC 243897335 37141041 185677084 243897335 37141041.

- ↑ Whitaker's Almanack, 1993, Concise Edition, (ISBN 0-85021-232-4), pages 134–136

- ↑ Victoria was 37 years and 326 days at the time of the birth of Beatrice, her youngest child. This is two days older than Queen Elizabeth II was at the time of the birth of Prince Edward in 1964. Victoria remains the oldest English or British Queen Regnant to have given birth.

Further reading

- Auchincloss, Louis. Persons of Consequence: Queen Victoria and Her Circle. Random House, 1979. ISBN 0-394-50427-5

- Benson, Arthur Christopher & Esher (Viscount). The Letters of Queen Victoria: A Selection From Her Majesty's Correspondence Between The Years 1837 and 1861. John Murray, 1908

- Carter, Miranda. Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to the First World War. London, Penguin. 2009. ISBN 9780670915569

- Cecil, Algernon. Queen Victoria and Her Prime Ministers. Eyre and Spottiswode, 1953.

- Eilers, Marlene A. Queen Victoria's Descendants. 2d enlarged & updated ed. Falköping, Sweden: Rosvall Royall Books, 1997. ISBN 0-8063-1202-5

- Hibbert, Christopher. Queen Victoria: A Personal History. Harper Collins Publishing, 2000.

- Hicks, Kyra E. "Martha Ann's Quilt for Queen Victoria". Brown Books, 2007. ISBN 978-1-933285-59-7

- Kirwn, Anna. "The royal diaries; Victoria. May blossom of Britannia" Scholastic Inc. New York, 2001

- Longford, Elizabeth Victoria R.I. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998. ISBN 0-297-84142-4.

- Marshall, Dorothy. The Life and Times of Queen Victoria. George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd, 1972.

- Packard, Jerrold M. Victoria's Daughters. St. Martin's Press, 1998. ISBN 0 312 24496 7

- Potts, D. M. & W. T. W. Potts. Queen Victoria's Gene: Haemophilia and the Royal Family. Alan Sutton, 1995. ISBN 0-7509-1199-9

- St. Aubyn, Giles. Queen Victoria: A Portrait. Sinclair-Stevenson, 1991. ISBN 1 85619 086 2

- Strachey, Lytton. Queen Victoria. Londres, Chatto et Windus Publishers, 1921. ISBN 2-228-88610-6

- Waller, Maureen, "Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power. The Six Reigning Queens of England". St. Martin's Press, New York, 2006. ISBN 0-312-33801-5

- Woodham-Smith, Cecil (1972) Queen Victoria: Her Life and Times, London: Hamish Hamilton, ISBN 0241022002

External links

- The letters of Queen Victoria Volume I at archive.org

- The letters of Queen Victoria Volume II at archive.org

- The letters of Queen Victoria Volume III at archive.org

- The Death of Queen Victoria Original reports from The Times

- Speeches in Parliament at archive.org

- Leaves from the journal of our life in the Highlands, from 1848–1861, memoir at archive.org

- More leaves from the journal of a life in the Highlands, from 1862 to 1882, memoir at archive.org

- Queen Victoria Memorial Page at Find a Grave

- Historica’s Heritage Minute video docudrama “Responsible Government.” (Adobe Flash Player.)

- Archival material relating to Victoria of the United Kingdom listed at the UK National Register of Archives

- Historical Images of Slough Railway Station Queen Victoria's first rail journey

- Historical Images of Constitution Hill, London. Scene of failed assassinations on Queen Victoria

- Historical Images of Osborne House one of the royal residences held by Queen Victoria

- Images of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee at Westminster Abbey

- Historical Images of The Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore which Victoria ordered to be built following the death of Prince Albert

|

Victoria of the United Kingdom

House of Hanover

Cadet branch of the House of Welf

Born: 24 May 1819 Died: 22 January 1901 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William IV |

Queen of the United Kingdom 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901 |

Succeeded by Edward VII |

| Vacant

Title last held by

Bahadur Shah IIas Mughal emperor |

Empress of India 1 May 1876 – 22 January 1901 |

|

| British royalty | ||

| Preceded by Prince William, Duke of Clarence |

Heir to the throne as heiress presumptive 26 June 1830 – 20 June 1837 |

Succeeded by Ernest Augustus I of Hanover |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)