Wellington

| Wellington Te Whanga-nui-a-Tara |

|

|---|---|

| — main urban area — | |

|

|

| Nickname(s): Harbour City | |

|

|

| Coordinates: | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Wellington |

| Territorial authorities | Wellington City Lower Hutt City Upper Hutt City Porirua City |

| Area[1] | |

| - Urban | 444 km2 (171.4 sq mi) |

| - Metro | 1,390 km2 (536.7 sq mi) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (June 2010 estimate)[2][3] | |

| - Urban | 389,700 |

| - Urban density | 877.7/km2 (2,273.2/sq mi) |

| Time zone | NZST (UTC+12) |

| - Summer (DST) | NZDT (UTC+13) |

| Postcode(s) | 6000 group, and 5000 and 5300 series |

| Area code(s) | 04 |

| Local iwi | Ngāti Poneke, Ngāti Tama, Te Āti Awa |

| Website | http://www.wellingtonnz.com/ |

Wellington (pronounced /ˈwɛlɪŋtən/) is the capital city and third most populous urban area of New Zealand. The urban area is situated on the southwestern tip of the country's North Island, and lies between Cook Strait and the Rimutaka Range. It is home to 389,700 residents, with an additional 3,700 residents living in the surrounding rural areas.

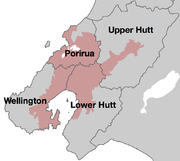

The Wellington urban area is the major population centre of the southern North Island, and is the seat of the Wellington Region - which in addition to the urban area covers the Kapiti Coast and Wairarapa. The urban area includes four cities: Wellington City, on the peninsula between Cook Strait and Wellington Harbour, contains the central business district and about half of Wellington's population; Porirua City on Porirua Harbour to the north is notable for its large Māori and Pacific Island communities; Lower Hutt City and Upper Hutt City are largely suburban areas to the northeast, together known as the Hutt Valley.

The 2009 Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranked Wellington 12th in the world on its list.[4]

Name

Wellington was named after Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington and victor of the Battle of Waterloo. The Duke's title comes from the town of Wellington in the English county of Somerset.

In Māori, Wellington goes by three names. Te Whanga-nui-a-Tara refers to Wellington Harbour and means "the great harbour of Tara".[5] Pōneke is a transliteration of Port Nick, short for Port Nicholson (the city's central marae, the community supporting it and its kapa haka have the pseudo-tribal name of Ngāti Pōneke).[6] Te Upoko-o-te-Ika-a-Māui, meaning The Head of the Fish of Māui (often shortened to Te Upoko-o-te-Ika), a traditional name for the southernmost part of the North Island, derives from the legend of the fishing up of the island by the demi-god Māui.

Importance

Wellington is New Zealand's political centre, housing Parliament, the head offices of all Government Ministries and Departments and the bulk of the foreign diplomatic missions that are based in New Zealand.

Wellington's compact city centre supports an arts scene, café culture and nightlife much larger than many cities of a similar size. It is an important centre of New Zealand's film and theatre industry, and second to Auckland in terms of numbers of screen industry businesses.[7] Te Papa Tongarewa (the Museum of New Zealand), the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, the Royal New Zealand Ballet, Museum of Wellington City & Sea and the biennial New Zealand International Arts Festival are all sited there.

Wellington has the 12th best quality of living in the world in 2009,[8] a ranking holding steady from 2007, according to a 2007 study by consulting company Mercer. Of cities with English as the primary language, Wellington ranked fourth in 2007.[9] Of cities in the Asia Pacific region, Wellington ranked third (2009) behind Auckland and Sydney, Australia.[8] Wellington became much more affordable, in terms of cost of living relative to cities worldwide, with its ranking moving from 93rd (more expensive) to 139th (less expensive) in 2009, probably as a result of currency fluctuations during the global economic downturn from March 2008 to March 2009.[10] "Foreigners get more bang for their buck in Wellington, which is among the cheapest cities in the world to live", according to a 2009 article, which reported that currency fluctuations make New Zealand cities affordable for multi-national firms to do business, and elaborated that "New Zealand cities were now more affordable for expatriates and were competitive places for overseas companies to develop business links and send employees".[11]

Settlement

Legend recounts that Kupe discovered and explored the district in about the tenth century.

European settlement began with the arrival of an advance party of the New Zealand Company on the ship Tory, on 20 September 1839, followed by 150 settlers on the Aurora on 22 January 1840. The settlers constructed their first homes at Petone (which they called Britannia for a time) on the flat area at the mouth of the Hutt River. When that proved swampy and flood-prone they transplanted the plans, which had been drawn without regard for the hilly terrain.

Earthquakes

Wellington suffered serious damage in a series of earthquakes in 1848[12] and from another earthquake in 1855. The 1855 Wairarapa earthquake occurred on a fault line to the north and east of Wellington. It ranks as probably the most powerful earthquake in recorded New Zealand history,[13] with an estimated magnitude of at least 8.2 on the Richter scale. It caused vertical movements of two to three metres over a large area, including raising an area of land out of the harbour and turning it into a tidal swamp. Much of this land was subsequently reclaimed and is now part of Wellington's central business district. For this reason the street named Lambton Quay now runs 100 to 200 metres (325 to 650 ft) from the harbour. Plaques set into the footpath along Lambton Quay mark the shoreline in 1840 and thus indicate the extent of the uplift and reclamation.

The area has high seismic activity even by New Zealand standards, with a major fault line running through the centre of the city, and several others nearby. Several hundred more minor fault lines have been identified within the urban area. The inhabitants, particularly those in high-rise buildings, typically notice several earthquakes every year. For many years after the 1855 earthquake, the majority of buildings constructed in Wellington were made entirely from wood. The 1996-restored Government Buildings,[14] near Parliament is the largest wooden office building in the Southern Hemisphere. While masonry and structural steel have subsequently been used in building construction, especially for office buildings, timber framing remains the primary structural component of almost all residential construction. Residents also place their hopes of survival in good building regulations, which gradually became more stringent in the course of the twentieth century.

New Zealand's capital

In 1865, Wellington became the capital of New Zealand, replacing Auckland, which William Hobson had established as the capital in 1841. Parliament first sat in Wellington on 7 July 1862, but the city did not become the official capital for some time. In November 1863 the Premier Alfred Domett moved a resolution before Parliament (in Auckland) that "... it has become necessary that the seat of government ... should be transferred to some suitable locality in Cook Strait." Apparently there was concern that the southern regions, where the gold fields were located, would form a separate colony. Commissioners from Australia (chosen for their neutral status) pronounced the opinion that Wellington was suitable because of its harbour and central location. Parliament officially sat in Wellington for the first time on 26 July 1865. The population of Wellington was then 4,900.[15]

Wellington is the seat of New Zealand's highest court, the Supreme Court of New Zealand. The historic former High Court building has been enlarged and restored for the court's use.

Government House, the official residence of the Governor-General, is in Newtown, opposite the Basin Reserve.

Geography

Wellington is at the south-western tip of the North Island on Cook Strait, the passage that separates the North and South Islands. On a clear day the snowcapped Kaikoura Ranges are visible to the south across the strait. To the north stretch the golden beaches of the Kapiti Coast. On the east the Rimutaka Range divides Wellington from the broad plains of the Wairarapa, a wine region of national acclaim.

With a latitude of 41° 17' S, Wellington is the southernmost national capital city in the world.[16] It is also the most remote capital in the world (i.e. the furthest from any other capital). It is more densely populated than most other settlements in New Zealand, due to the small amount of building space available between the harbour and the surrounding hills. Wellington has very few suitable areas in which to expand and this has resulted in the development of the surrounding cities in the greater urban area. Because of its location in the roaring forties latitudes and its exposure to omnipresent winds coming through Cook Strait, the city is known to Kiwis as "Windy Wellington".

More than most cities, life in Wellington is dominated by its central business district (CBD). Approximately 62,000 people work in the CBD, only 4,000 fewer than work in Auckland's CBD, despite that city having three times Wellington's population. Wellington's cultural and nightlife venues concentrate in Courtenay Place and surroundings located in the southern part of the CBD, making the inner city suburb of Te Aro the largest entertainment destination in New Zealand.

Wellington has a median income well above the average in New Zealand[17] and a much higher proportion of people with tertiary qualifications than the national average.[18]

Wellington has a reputation for its picturesque natural harbour and green hillsides adorned with tiered suburbs of colonial villas. The CBD is sited close to Lambton Harbour, an arm of Wellington Harbour. Wellington Harbour lies along an active geological fault, which is clearly evident on its straight western coast. The land to the west of this rises abruptly, meaning that many of Wellington's suburbs sit high above the centre of the city.

There is a network of bush walks and reserves maintained by the Wellington City Council and local volunteers. The Wellington region has 500 square kilometres (190 sq mi) of regional parks and forests.

In the east is the Miramar Peninsula, connected to the rest of the city by a low-lying isthmus at Rongotai, the site of Wellington International Airport. The narrow entrance to Wellington is directly to the east of the Miramar Peninsula, and contains the dangerous shallows of Barrett Reef, where many ships have been wrecked (most famously the inter-island ferry Wahine in 1968).[19]

On the hill west of the city centre are Victoria University and Wellington Botanic Garden. Both can be reached by a funicular railway, the Wellington Cable Car.

Wellington Harbour has three islands: Matiu/Somes Island, Makaro/Ward Island and Mokopuna Island. Only Matiu/Somes Island is large enough for settlement. It has been used as a quarantine station for people and animals and as an internment camp during the First and Second World Wars. It is now a conservation island, providing refuge for endangered species, much like Kapiti Island further up the coast. There is access during daylight hours by the Dominion Post Ferry.

Climate

The city averages 2025 hours (or about 169 days) of sunshine per year.[20] The climate is a temperate marine one, is generally moderate all year round, and rarely sees temperatures rise above 25 °C (77 °F), or fall below 4 °C (39 °F). The hottest recorded temperature in the city is 31.1 °C (88 °F), while -1.9 °C (28 °F) is the coldest. The city is notorious however for its southerly blasts in winter, which may make the temperature feel much colder. The city is generally very windy all year round with high rainfall; average annual rainfall is 1249 mm, June and July being the wettest months. Frosts are quite common in the hill suburbs and the Hutt Valley between May and September. Snow is very rare, although snow was reported to have fallen on the city on July 17, 1995.[21]

| Climate data for Wellington, New Zealand | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

19 (66) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

12 (54) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12 (54) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15 (59) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9 (48) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.2 (54) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 72 (2.83) |

62 (2.44) |

92 (3.62) |

100 (3.94) |

117 (4.61) |

147 (5.79) |

136 (5.35) |

123 (4.84) |

100 (3.94) |

115 (4.53) |

99 (3.9) |

86 (3.39) |

1,249 (49.17) |

| Sunshine hours | 246 | 209 | 191 | 155 | 128 | 98 | 117 | 136 | 156 | 193 | 210 | 226 | 2,065 |

| Source: NIWA[22] | |||||||||||||

Architecture

Wellington showcases a variety of architectural styles from the past 150 years - nineteenth century wooden cottages, such as the Italianate Katherine Mansfield Birthplace in Thorndon, some streamlined Art Deco structures such as the old Wellington Free Ambulance headquarters, the City Gallery, and the Former Post and Telegraph Building, as well as the curves and vibrant colours of post-modern architecture in the CBD.

The oldest building in Wellington is the late Georgian Colonial Cottage in Mount Cook.[23] The tallest building in the city is the Majestic Centre on Willis Street at 116 metres high,[24] the second tallest being the structural expressionist BNZ Tower at 103 metres.[25] Futuna Chapel is located in Karori, was the first bicultural building in New Zealand, and is thus considered one of the most significant New Zealand buildings of the twentieth century.

Old Saint Paul's is an example of 19th-century Gothic Revival architecture adapted to colonial conditions and materials, as is Saint Mary of the Angels. The Museum of Wellington City & Sea building, the Bond Store is in the Second French Empire style, and the Wellington Harbour Board Wharf Office Building is in a late English Classical style. There are several restored theatre buildings, the St. James Theatre, the Opera House and the Embassy Theatre.

Civic Square is surrounded by the Town Hall and council offices, the Michael Fowler Centre, the Wellington Central Library, Capital E (Home of the National Theatre for Children), the City-to-Sea Bridge, and the City Gallery.

Because it is the capital there are many notable government buildings in Wellington. Both the National Library of New Zealand, located on Molesworth Street, and the Te Puni Kōkiri building on Lambton Quay are aesthetically unique . The circular-conical Executive Wing of New Zealand Parliament Buildings, located on the corner of Lambton Quay and Molesworth Street, was constructed in the mid-60s and is commonly referred to as the Beehive. Across the road from the Beehive is the largest wooden building in the Southern Hemisphere,[26] part of the old Government Buildings which now houses part of Victoria University of Wellington's Law Faculty. Further afield, Victoria University's Coastal Ecology Laboratory on the south coast of Wellington is an arresting new structure that was completed in early 2009.

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is on the waterfront.

As tastes and trends in architecture have come into and fallen out of fashion, many memorable buildings have been lost.

Wellington also contains many iconic sculptures and structures. Elijah Wood mentioned that he urinated in the Bucket Fountain in Cuba Street in an interview with Jay Leno.[27] More recently a number of new kinetic sculptures were commissioned, such as the Zephyrometer.[28] This giant 26-metre orange spike built for movement by artist Phil Price has been described as "tall, soaring and elegantly simple" and which "reflects the swaying of the yacht masts in the Evans Bay Marina behind it" and "moves like the needle on the dial of a nautical instrument, measuring the speed of the sea or wind or vessel."[29]

Housing and real estate

Wellington experienced a real estate boom in the early 2000s and the effects of the international property bust at the start of 2007. In 2005, the market was described as "robust".[30] But by 2008, property values declined by about 9.3% over a twelve month period, according to one estimate. More expensive properties declined more steeply in value, sometimes declining as much as 20%.[31] "From 2004 to early 2007, rental yields were eroded and positive cash flow property investments disappeared as house values climbed faster than rents. Then that trend reversed and yields slowly began improving," according to two New Zealand Herald reporters writing in May 2009.[32] In the middle of 2009, house prices had dropped, interest rates were low, and buy-to-let property investment was again looking attractive, particularly the Lambton precinct in Wellington, according to these two reporters.[32]

The Wellington City Council conducted a survey in March 2009 and found the typical apartment dweller was a New Zealand native aged 24 to 35 with a professional job in the downtown area, with household income higher than surrounding areas. Three quarters (73%) walked to work or university, 13% traveled by car, 6% by bus, 2% bicycled (although 31% own bicycles), and didn't travel that far, since most (73%) worked or studied in the central city area. The large majority (88%) didn't have children in their apartments; 39% were couples without children; 32% were single person households; 15% were groups of people "flatting together". Most (56%) owned their apartment; 42% rented (of renters, 16% paid $351 to $450 per week, 13% paid less and 15% paid more—only 3% paid more than $651 per week). The report continued: "The four most important reasons for living in an apartment were given as lifestyle and city living (23 per cent), close to work (20 per cent), close to shops and cafes (11 per cent) and low maintenance (11 per cent) ... City noise and noise from neighbours were the main turnoffs for apartment dwellers (27 per cent), followed by a lack of outdoor space (17 per cent), living close to neighbours (9 per cent) and apartment size and a lack of storage space (8 per cent)."[33]

Wellington households are primarily one-family, making up two thirds (67%) of households, followed by single-person households (25%); there were fewer multiperson households and even fewer households containing two or more families. These counts are from the 2006 census and pertain to the Wellington region (which includes the surrounding area in addition to the four cities area).[34]

Energy

The energy needs of the Wellington area are increasing, and one new source is the wind. Project West Wind was granted resource consent for 66 turbines, which is estimated to generate approximately 140MW.[35] Meridian Energy's Project West Wind is located a few kilometres west of Wellington's central business district, located on Meridian's Quartz Hill and Terawhiti Station. Near Project West Wind is the new proposed project Mill Creek - this is in neighbouring suburbs; Ohariu Valley (behind Johnsonville) and the back of Porirua. It will be smaller than project West Wind, but its exact size is still unknown - as it is going through the environment courts. In April 2009, a $440 million wind farm was connected to the power grid, including twenty 111 meter high turbines, and it is expected that by the end of 2009, there will be 62 turbines (each with 40 meter long blades) generating enough power for 70,000 homes.[36]

Wellington's windy conditions, while perfect for wind farms, sometimes take down power lines; in May 2009, one windstorm left about 2500 residents without power for a few hours.[37] In addition, infrastructure upgrades as well as lightning sometimes cause occasional power blackouts.[38]

While electricity is supplied by national power grid operator named Transpower New Zealand Limited,[39] Wellington's electricity network is owned and managed by a Hong Kong firm named Cheung Kong Infrastructure Holdings which purchased the network in 2008 (the sale generated much political controversy).[40]

Demographics

The urban area of Wellington stretches across the city council areas of Wellington, Lower Hutt, Upper Hutt and Porirua.

Population

The four cities have a total population of 393,600 (June 2010 estimate),[3] and the Wellington urban area contains 99% of that population. The remaining areas are largely mountainous and sparsely farmed or parkland and are outside the urban area boundary.

Counts from the 2006 census gave totals by area, sex, and age. Wellington City had the largest population of the four city council areas with 179,466 people, followed by Lower Hutt City, Porirua, and Upper Hutt City. Women outnumber men in all four areas, according to data from Statistics New Zealand, particularly in the Wellington City area.[41]

Wellington Population by Area and Sex ( 2006 Census )

| Area | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wellington City | 179 466 | 86 932 | 92 532 |

| Lower Hutt City | 97 701 | 47 703 | 49 998 |

| Upper Hutt City | 38 415 | 19 088 | 19 317 |

| Porirua City | 48 546 | 23 634 | 24 912 |

| Total four cities | 364 128 | 177 369 | 186 759 |

Source:Statistics New Zealand (2006 Census)[41]

Age distribution

Age distributions for the four city regions are given (see table below). Overall, Wellington's age structure closely matches the national distribution. The relative lack of older people in Wellington is less marked when the neighbouring Kapiti Coast District is included. Nearly 7% of Kapiti Coast residents are over 80.

Wellington Area - Age Distribution by Area

| Area | Under 20 | 20–39 | 40–59 | 60–79 | 80 and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wellington City | 25% | 37% | 26% | 10% | 2% |

| Lower Hutt City | 30% | 27% | 27% | 12% | 3% |

| Upper Hutt City | 30% | 25% | 28% | 14% | 3% |

| Porirua City | 34% | 27% | 26% | 10% | 1% |

| Total four cities | 28% | 32% | 27% | 11% | 2% |

| New Zealand | 29% | 27% | 27% | 14% | 3% |

Source:Statistics New Zealand (2006 Census)[42]

Arts and culture

Film

Filmmaker Peter Jackson, Richard Taylor and a growing team of creative professionals have turned the eastern suburb of Miramar into one of the world's most acclaimed film-making infrastructures, giving rise to the moniker 'Wellywood'. Jackson's companies include Weta Workshop, Weta Digital, Camperdown Studios, Park Road Post, and Stone Street Studios near Wellington Airport.[43]. Recent films shot in Wellington include the Lord of The Rings trilogy, King Kong and Avatar. Jackson described Wellington in this way: "Well, it's windy. But it's actually a lovely place, where you're pretty much surrounded by water and the bay. The city itself is quite small, but the surrounding areas are very reminiscent of the hills up in northern California, like Marin County near San Francisco and the Bay Area climate and some of the architecture. Kind of a cross between that and Hawaii."[44]

Wellington directors Jane Campion and Vincent Ward have managed to reach the world's screens with their independent spirit. Emerging Kiwi film-makers, like Robert Sarkies, Taika Waititi, Costa Botes and Jennifer Bush-Daumec,[45] are extending the Wellington-based lineage and cinematic scope. There are agencies to assist film-makers with such tasks as securing permits and scouting locations.[46]

Wellington has a large number of independent cinemas, including The Embassy, Paramount, The Empire, Penthouse and Light House, which participate in film festivals throughout the year. Wellington is also one of fifteen locations for the annual New Zealand International Film Festival. In 2010, the film festival will take place from July 16 to August 1.[47]

Museums and cultural institutions

Wellington is home to Te Papa (the Museum of New Zealand), the Museum of Wellington City & Sea, the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Museum, Colonial Cottage, the New Zealand Cricket Museum, the Cable Car Museum, Old Saint Paul's, and the Wellington City Art Gallery.

Food

Wellington's café culture is prominent. The city has more cafes per capita than New York City.[48] Restaurants are either licensed to sell alcohol, BYO (bring your own), or unlicensed (no alcohol); many let you bring your own wine.[49] Restaurants offer a variety of cuisines, including from Europe, Asia and Polynesia. "For dishes that have a distinctly New Zealand style, there's lamb, pork and cervena (venison), salmon, crayfish (lobster), bluff oysters, paua (abalone), mussels, scallops, pipis and tuatua (both are types of New Zealand shellfish); kumara (sweet potato); kiwifruit and tamarillo; and pavlova, the national dessert," recommends one tourism website.[50]

Festivals

Wellington has become home to a myriad of high-profile events and cultural celebrations, including the biennial New Zealand International Arts Festival, biennial Wellington Jazz Festival, biennial Capital E National Arts Festival for Children and major events such as World of Wearable Art, Cuba Street Carnival, New Zealand Fringe Festival, New Zealand International Comedy Festival (also hosted in Auckland), Summer City, The Wellington Folk Festival (in Wainuiomata), New Zealand Affordable Art Show, the New Zealand Sevens Weekend and Parade, Out in the Square, Vodafone Homegrown, the Couch Soup theater festival, and numerous film festivals.

Music

The local music scene has, over the years, produced bands such as The Warratahs, The Phoenix Foundation, Shihad, Fly My Pretties, Rhian Sheehan, Fat Freddy's Drop, The Black Seeds, Fur Patrol, Flight of the Conchords, Connan and the Mockasins, Rhombus and Module. The New Zealand School of Music was established in 2005 through a merger of the conservatory and theory programmes at Massey University and Victoria University of Wellington. New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Nevine String Quartet and Chamber Music New Zealand are based in Wellington. The city is also home to an Internationally-renowned men's A Cappella chorus called Vocal FX.

Performing arts

Wellington is home to the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, City Gallery, the Royal New Zealand Ballet, St James' Theatre, Downstage Theatre, Bats Theatre, Circa Theatre, The National Maori Theatre company Taki Rua, the National Theatre for Children at Capital E in Civic Square and the New Zealand International Arts Festival; the Wellington Performing Arts Centre is also an important local source for theatre.

Wellington is also home to groups that perform Improvised Theatre and Improvisational comedy, including Wellington Improvisation Troupe (WIT), The Improvisors and youth group, Joe Improv. Poet Bill Manhire, director of the International Institute of Modern Letters, has turned the Creative Writing Programme at Victoria University of Wellington into a forge of new literary activity. Te Whaea, New Zealand's university-level school of dance and drama, and tertiary institutions such as The Learning Connexion, offer training and creative development.

Comedy

Wellington has a small but thriving comedy scene, aided in recent years by the emergence of the Fringe Bar as the home for Wellington comedy. The venue hosts up to four nights of comedy eavery week, with a mix of stand-up, improv and sketch. The monthly El Jaguar Fiesta de Variety showcases a mix of music, singing, burlesque, and comedy.[51]. Other venues which host comedy in Wellington include the San Francisco Bath House and the Katipo Cafe.

Many of New Zealand's preeminent comedians have either come from Wellington or have got their start there; such as Ginette McDonald ("Lynn of Tawa"), Raybon Kan, Dai Henwood, Ben Hurley, Steve Wrigley, and most famously Flight of the Conchords and the satirist John Clarke ("Fred Dagg") who later found even greater fame after he moved to Australia.

The sketch groups Breaking the 5th Wall [52] and the all female group Little Moustache [53] both operate out of Wellington and have regular shows around the city.

Wellington is also home to groups that perform improvised theatre and improvisational comedy, including Wellington Improvisation Troupe (WIT), The Improvisors and youth group, Joe Improv.

Wellington also hosts shows in the annual New Zealand International Comedy Festival. The NZ International Comedy Fest 2010 featured over 250 local and international comedy acts and was a revolutionary first incorporating an iPhone application for the Festival.[54]

Arts

From 1936 to 1992 Wellington was home to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand, when it was amalgamated into Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington is also home to the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts and the Arts Foundation of New Zealand. The city's new arts centre, Toi Poneke, serves as a nexus of creative projects, collaborations, and multi-disciplinary production. Arts Programmes and Services Manager Eric Vaughn Holowacz and a small team based in the Abel Smith Street facility have produced ambitious new initiatives such as Opening Notes, Drive by Art, the annual children's Artsplash Festival, and new public art projects. The city is also home to experimental arts publication White Fungus Magazine.

Sport

Wellington is the home to:

- The Hurricanes - Super 14 rugby team representing the Lower North Island, primarily based in Wellington

- Wellington Lions - ITM Cup rugby team

- Wellington Phoenix FC - football (soccer) club playing in the Australasian A-League, the only fully professional football club in New Zealand

- Team Wellington - Wellington's franchise in the semi-professional New Zealand Football Championship

- Central Pulse - netball franchise representing the Lower North Island in the ANZ Championship, primarily based in Wellington

- Wellington Firebirds and Wellington Blaze - men's and women's cricket teams

- Wellington Saints - basketball team competing in New Zealand's National Basketball League

Sporting events hosted in Wellington include:

- the Wellington Sevens - a round of the IRB Sevens World Series Held at the Westpac Stadium over several days every February, this rugby sevens tournament contributes $6.8 million to the local economy each year.

- the World Mountain Running Championships in 2005.

- a Wellington 500 street race for touring cars, between 1985 and 1996

- the McEvedy Shield - annual athletics meet for college students from Rongotai College, St Patrick's College (Silverstream), St Patrick's College (Town), and Wellington College

Education

Wellington offers a variety of college and university programs for students.

Victoria University of Wellington (Te Whare Wānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a Māui) has four campuses across the city and works with a three trimester system (beginning March, July, and November).[55] It enrolled 21,380 students in 2008; of these, 16,609 were full-time students. Of all students, 56% were female and 44% male. While the student body was primarily New Zealanders of European descent, 1,713 were Maori, 1,024 were Pacific students, 2,765 were international students. 5,751 degrees, diplomas and certificates were awarded. The school has 1,930 full-time employees.[56]

Massey University has a Wellington campus known as the "creative campus" and offers programs in communication and business, engineering and technology, health and well-being, and creative arts. Its school of design was established in 1886, and has research centers for studying public health, sleep, Maori health, small & medium enterprises, disasters, and tertiary teaching excellence.[57] It combined with Victoria University of Wellington to create the New Zealand School of Music.[57]

The University of Otago has a Wellington branch with its Wellington School of Medicine and Health.

In addition, there is the Wellington Institute of Technology. For further information, see List of universities in New Zealand.

The Wellington area has numerous schools for college preparation and study. See List of schools in the Wellington Region for more information.

Transport

Wellington is served to the north by State Highway 1 in the west and State Highway 2 in the east, meeting at the Ngauranga Interchange north of the city centre, where SH 1 runs through the city to the airport. Road access into the capital is lower in grade that most other cities in New Zealand - between Wellington and the Kapiti Coast, SH 1 travels along the Centennial Highway, an narrow accident-prone section of road, and between Wellington and Wairarapa, SH 2 transverses the Rimutaka Ranges on a similar narrow accident-prone road. Wellington has two short motorways, both part of SH 1: the Johnsonville-Porirua Motorway and the Wellington Urban Motorway, which in combination with a small non-motorway section in the Ngauranga Gorge, connect Porirua with Wellington City.

Bus transport in Wellington is supplied by several different operators under the banner of Metlink. Buses serve almost every part of Wellington City, with most of them running along the "Golden Mile" from Wellington Railway Station to Courtenay Place. Most of the buses run on diesel, but nine routes within Wellington use trolleybuses - the only remaining public system in Oceania.

Wellington lies at the southern end of the North Island Main Trunk Railway (NIMT) and the Wairarapa Line, converging on Wellington Railway Station at the northern end of central Wellington. Two long-distance services leave from Wellington Railway Station: the Capital Connection, for commuters from Palmerston North, and The Overlander to Auckland. During 2006, there was serious discussion to eliminate the Overlander train service altogether because of lack of passengers; a railway spokesperson said the number of passengers was so low that "we could not justify keeping it going".[59] In September 2006, however, the rail operator announced there would be continued service but on a reduced basis (Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays in the off-peak winter season, and daily in the peak summer and Easter period).[60][61][62]

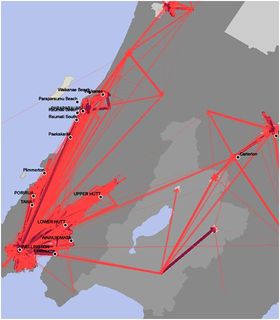

Four electrified suburban lines radiate out of Wellington Railway Station to the outer suburbs - the Johnsonville Line north to the northern Wellington City suburbs, ending at Johnsonville; the Paraparaumu Line along the NIMT to Porirua and to Paraparaumu on the Kapiti Coast; the Melling Line to Lower Hutt City centre via Petone, and the Hutt Valley Line along the Wairarapa Line via Waterloo and Taita to Upper Hutt. A diesel-hauled carriage service, the Wairarapa Connection, connects several times daily to Masterton in the Wairarapa via the 8.8-kilometre (5.5 mi) long Rimutaka Tunnel.

Wellington is the northern terminus of Cook Strait ferries to Picton in the South Island, provided by state-owned Interislander and private Bluebridge. Local ferries connect Wellington city centre with Eastbourne, Seatoun and Petone.

Wellington International Airport is 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) south-east of the city. It is serviced by flights from across New Zealand, and several flights to Australia and the Pacific Islands. Flights to other international destinations require a transfer at another airport, as larger aircraft cannot use Wellington's short (1,936-metre / 6,352 ft) runway. The airport is a base for Wellington Aero Club, a private not-for-profit aeronautical flight school.[63][64]

Gallery

Notable Wellingtonians

Sister-city relationships

Sister-city relationships are at the local government level:

- Wellington City sister-cities

- Porirua sister-cities

- Lower Hutt sister-cities

- Upper Hutt sister-cities

See also

- The Bucket Fountain

- Civic Square

- Courtenay Place

- Cuba Street

- Helengrad

- Lambton Quay

- Public transport in Wellington

- Reclamation of Wellington Harbour

- Te Aro

- Wellywood

References

- ↑ "About Wellington - Facts & Figures". Wellington City Council. http://www.wellington.govt.nz/aboutwgtn/glance/index.html.. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ "Wellington City Council Annual Plan 2007-2008". http://www.wellington.govt.nz/plans/annualplan/0708/pdfs/03snapshot.pdf. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Subnational population estimates at 30 June 2010 (boundaries at 1 November 2010)". Statistics New Zealand. 26 October 2010. http://www.stats.govt.nz/~/media/Statistics/Methods%20and%20Services/Tables/Subnational%20population%20estimates/subnational-pop-estimate-jun2001-2010.ashx. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ↑ "Mercer's 2009 Quality of Living survey highlights". www.mercer.com. 28 April 2009. http://www.mercer.com/referencecontent.htm?idContent=1128060#Top50_qol. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ↑ "Te Āti Awa ki Te Whanganui-a-Tara" (in Māori). Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.teara.govt.nz/NewZealanders/MaoriNewZealanders/TeAtiAwaWellington/mi., orthographic conventions sourced from "Māori Language Commission". http://www.tetaurawhiri.govt.nz/english/pub_e/conventions2.shtml.

- ↑ "Poneke". New Zealand Department of Conservation. http://www.doc.govt.nz/templates/placeprofilesummary.aspx?id=35015.

- ↑ "Screen Industry Survey: 2007/08 -- (spreadsheet -- see pages 5, 8)". Statistics New Zealand. 2008. http://search.stats.govt.nz/nav/ct2/industrysectors_filmtelevision/ct1/industrysectors/0. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Quality of Living global city rankings 2009–Mercer survey". http://www.mercer.com/referencecontent.htm?idContent=1173105. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "Mercer 2007 World-wide quality of living survey". http://www.mercer.com/referencecontent.jhtml?idContent=1128060.

- ↑ "Worldwide Cost of Living survey 2009–City ranking released–Mercer survey". http://www.mercer.co.nz/homepage.htm?siteLanguage=100. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Kelly Burns (2009-08-07). "You get more for your money in Wellington". The Dominion Post. http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/business/2573142/You-get-more-for-your-money-in-Wellington. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ "The 1848 Marlborough earthquake - Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2005-03-30. http://www.teara.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/NaturalHazardsAndDisasters/HistoricEarthquakes/2/en. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ "The 1855 Wairarapa earthquake - Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2007-09-21. http://www.teara.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/NaturalHazardsAndDisasters/HistoricEarthquakes/3/en. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ "Government Buildings". Register of Historic Places. New Zealand Historic Places Trust. http://www.historic.org.nz/TheRegister/RegisterSearch/RegisterResults.aspx?RID=37&m=advanced. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ Phillip Temple: Wellington Yesterday

- ↑ Guinness World Records 2009. London, United Kingdom: Guinness World Records Ltd. 2008. p. 277. ISBN 9781904994367.

- ↑ "Living in Wellington". Career Services. 1 May 2007. http://www2.careers.govt.nz/life_wellington.html.

- ↑ "Wellington Facts & Figures - Census Summaries - 2006 - Occupation & Qualifications". Statistics New Zealand. http://www.wellington.govt.nz/aboutwgtn/glance/census/occupation.html.

- ↑ "New Zealand Disasters - Wahine Shipwreck". Christchurch City Libraries. 1968-04-10. http://christchurchcitylibraries.com/kids/nzdisasters/wahine.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ↑ "Mean Monthly Sunshine (hours)". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. http://www.niwascience.co.nz/edu/resources/climate/sunshine/.

- ↑ Tannis McCartney. "TravelBlog -- A Year at Pauatahanui Inlet". TravelBlog.org. http://www.travelblog.org/Oceania/New-Zealand/North-Island/Wellington-Region/Porirua/blog-286178.html. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "NIWA Climate Data 1971-2000". http://www.niwascience.co.nz/edu/resources/climate/.

- ↑ "Colonial Cottage". Colonialcottagemuseum.co.nz. http://www.colonialcottagemuseum.co.nz/home.html. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ SkyScraper City archive (accessed September 22, 2006)

- ↑ "Emporis.com". Emporis.com. 2006-11-11. http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=stateinsurancetower-wellington-newzealand. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ "Department of Conservation". Doc.govt.nz. 2006-08-29. http://www.doc.govt.nz/conservation/historic/by-region/wellington/poneke-area/government-buildings/. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ "The Bastards have Landed: The Peter Jackson Fanclub". Tbhl.theonering.net. http://tbhl.theonering.net/tbhlnews/news-archive-12-2003.html. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ "Kinetic Sculpture by Tony Nicholls - Enjoy Public Art Gallery". Texture - Wellington, New Zealand. 2008-09-23. http://texture.co.nz/blogs/reviews/archive/2008/09/23/kinetic-sculpture-by-tony-nicholls-enjoy-public-art-gallery.aspx. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ↑ Phil Price (kinetic sculptor) (2003). "Zephyrometer - The second of the Meridian Energy wind sculptures". Wellington Sculpture Trust. http://www.sculpture.org.nz/engine/SID/10018/AID/1105.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ↑ Anne Gibson (2005-08-03). "Robust market sprouts apartments". The New Zealand Herald. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=10338845. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Andrea Milner (2009-06-21). "Post properties get biggest pounding". The New Zealand Herald. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/wellington-region/news/article.cfm?l_id=153&objectid=10579767. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Andrea Milner and Jonathan Milne. "Real Estate: Rental buys looking good". The New Zealand Herald. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/property/news/article.cfm?c_id=8&objectid=10571367. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "It's a great life downtown ... except for the noise". The New Zealand Herald. 2009-04-14. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/wellington-city-council/news/article.cfm?o_id=240&objectid=10566448. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Quickstats about Wellington Region

- ↑ "Makara Wind Farm". http://tvnz.co.nz/view/page/411415/642358.

- ↑ "Wind farm begins to power national grid". The New Zealand Herald. 2009-04-30. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/electricity/news/article.cfm?c_id=187&objectid=10569481. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "High winds cause power outages in Wellington". The New Zealand Herald. 2009-05-15. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/wellington-region/news/article.cfm?l_id=153&objectid=10572504. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "Lightning blamed for Wellington blackout, gales on way". The New Zealand Herald. 2007-03-14. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/waikanae/news/article.cfm?l_id=522&objectid=10428709. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "Transpower apologizes for costly Auckland power black-out". The New Zealand Herald. 2009-02-12. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/wellington/news/article.cfm?l_id=325&objectid=10556467. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Paula Olivier (2008-04-29). "Govt won't pull plug on capital's power sale". The New Zealand Herald. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/politics/news/article.cfm?c_id=280&objectid=10506788. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Regional Summary Tables - 2006 Census of Population and Dwellings - Regional Summary Tables by territorial authority (spreadsheet)". Statistics New Zealand. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006-census-data/2006-census-reports/regional-summary-tables.aspx. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ↑ "Tables About Wellington Region - Age Group and Sex". Statistics New Zealand. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006CensusHomePage/Tables/AboutAPlace/SnapShot.aspx?type=region&tab=Agesex&id=1000009. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ↑ Rebecca Lewis (April 12, 2009). "High-flyer Peter Jackson's jet set upgrade". The New Zealand Herald. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/entertainment/news/article.cfm?c_id=1501119&objectid=10566283. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ↑ Mark Seal (2009). "Yo, Adrien!". American Way. http://www.americanwaymag.com/wellington-new-zealand-peter-jackson-adrien-brody-1. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ "Bushcraft official website". Bushcraft. 2009. http://www.bushcraft.co.nz/. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ "FilmWellington New Zealand". http://www.filmwellington.com/about-film-wellington/. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ↑ "New Zealand 10 International Film Festival". http://www.nzff.co.nz/. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ↑ "Living and working in Wellington". http://www.careers.govt.nz/default.aspx?id0=19906&id1=wellington.

- ↑ "Wellington Restaurants and Pubs". nz.com (New Zealand on the Web). http://www.wellington.nz.com/restaurant-pub.aspx. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ↑ "New Zealand Cuisine - Cuisine Influences". Media Resources - Tourism New Zealand's site for media and broadcast professionals. http://www.newzealand.com/travel/media/features/food-&-wine/food-wine_nzcuisine_backgrounder.cfm. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ↑ http://www.thefringebar.org

- ↑ http://www.bt5w.com

- ↑ www.littlemoustache.com/about_us/

- ↑ FishHead Magazine http://www.fishhead.co.nz/, Issue 1 April 2010, p.14

- ↑ "Victoria University of Wellington - website". Victoria University of Wellington. http://www.victoria.ac.nz/home/about/. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "Victoria in the year 2008". Victoria University of Wellington. http://www.victoria.ac.nz/home/about/snapshot.aspx. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Wellington Campus - the Creative Campus". Massey University. http://wellington.massey.ac.nz/. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "Commuterview New Zealand, 2006 Census of Population and Dwellings". Statistics New Zealand. July 2006. http://www.stats.govt.nz/about_us/about-statistics-new-zealand.aspx. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ . The New Zealand Herald. 2005. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/rail-transport/news/article.cfm?c_id=428&objectid=10393040. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "Overlander announcement". Scoop. 2006-09-28. http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/BU0609/S00483.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- ↑ "Overlander's final fate revealed today?". Newstalk ZB. 2006-09-27. http://www.newstalkzb.co.nz/newsdetail1.asp?storyID=104470. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- ↑ "Overlander train service continues". Newstalk ZB. 2006-09-28. http://www.newstalkzb.co.nz/newsdetail1.asp?storyID=104572. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- ↑ "About Us". Wellington Aero Club. 2009-08-28. http://www.flywellington.co.nz/?page_id=3. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ↑ ROSALEEN MACBRAYNE (July 11, 2000). "Body discovery stuns cousin". The New Zealand Herald. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=143681. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

External links

- Greater Wellington Regional Council

- Official NZ Tourism website for Wellington

- Wellington City Council

- Wellington in Te Ara the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Wellington travel guide from Wikitravel

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||