Hypothyroidism

| Hypothyroidism | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

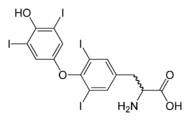

Thyroxine (T4) normally produced in 20:1 ratio to triiodothyronine (T3) |

|

| ICD-10 | E03.9 |

| ICD-9 | 244.9 |

| DiseasesDB | 6558 |

| eMedicine | med/1145 |

| MeSH | D007037 |

Hypothyroidism (pronounced /ˌhaɪpɵˈθaɪrɔɪdɪzəm/) is the disease state in humans and in vertebrates caused by insufficient production of thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland. Cretinism is a form of hypothyroidism found in infants.

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

In adults, hypothyroidism is associated with the following symptoms:[1][2][3]

Early

- Poor muscle tone (muscle hypotonia)

- Fatigue

- Cold intolerance, increased sensitivity to cold

- Constipation

- Depression

- Muscle cramps and joint pain

- Goiter

- Thin, brittle fingernails

- Thin, brittle hair

- Paleness

- Decreased sweating

- Dry, itchy skin

- Weight gain and water retention[4][5][6]

- Bradycardia (low heart rate – fewer than sixty beats per minute)

Late

- Slow speech and a hoarse, breaking voice – deepening of the voice can also be noticed, caused by Reinke's Edema.

- Dry puffy skin, especially on the face

- Thinning of the outer third of the eyebrows (sign of Hertoghe)

- Abnormal menstrual cycles

- Low basal body temperature

Uncommon

- Impaired memory[7]

- Impaired cognitive function (brain fog) and inattentiveness.[8]

- A slow heart rate with ECG changes including low voltage signals. Diminished cardiac output and decreased contractility.

- Reactive (or post-prandial) hypoglycemia[9]

- Sluggish reflexes

- Hair loss

- Anemia caused by impaired haemoglobin synthesis (decreased EPO levels), impaired intestinal iron and folate absorption or B12 deficiency[10] from pernicious anemia

- Difficulty swallowing

- Shortness of breath with a shallow and slow respiratory pattern.

- Increased need for sleep

- Irritability and mood instability

- Yellowing of the skin due to impaired conversion of beta-carotene[11] to vitamin A

- Impaired renal function with decreased glomerular filtration rate

- Elevated serum cholesterol

- Acute psychosis (myxedema madness) (a rare presentation of hypothyroidism)

- Decreased libido[12] due to impairment of testicular testosterone synthesis

- Decreased sense of taste and smell (anosmia)

- Puffy face, hands and feet (late, less common symptoms)

- Gynecomastia

Causes

About three percent of the general population is hypothyroid.[13] Factors such as iodine deficiency or exposure to Iodine-131 (I-131) can increase that risk. There are a number of causes for hypothyroidism. Iodine deficiency is the most common cause of hypothyroidism worldwide. In iodine-replete individuals hypothyroidism is generally caused by Hashimoto's thyroiditis, or otherwise as a result of either an absent thyroid gland or a deficiency in stimulating hormones from the hypothalamus or pituitary.

Hypothyroidism can result from postpartum thyroiditis, a condition that affects about 5% of all women within a year of giving birth. The first phase is typically hyperthyroidism; the thyroid then either returns to normal, or a woman develops hypothyroidism. Of those women who experience hypothyroidism associated with postpartum thyroiditis, one in five will develop permanent hypothyroidism requiring life-long treatment.

Hypothyroidism can also result from sporadic inheritance, sometimes autosomal recessive.

Hypothyroidism is also a relatively common disease in domestic dogs, with some specific breeds having a definite predisposition.[14]

Temporary hypothyroidism can be due to the Wolff-Chaikoff effect. A very high intake of iodine can be used to temporarily treat hypothyroidism, especially in an emergency situation. Although iodine is substrate for thyroid hormones, high levels prompt the thyroid gland to take in less of the iodine that is eaten, reducing hormone production.

Hypothyroidism is often classified by association with the indicated organ dysfunction (see below):[15][16]

| Type | Origin | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | Thyroid gland | The most common forms include Hashimoto's thyroiditis (an autoimmune disease) and radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. |

| Secondary | Pituitary gland | Occurs if the pituitary gland does not create enough thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to induce the thyroid gland to produce enough thyroxine and triiodothyronine. Although not every case of secondary hypothyroidism has a clear-cut cause, it is usually caused by damage to the pituitary gland, as by a tumor, radiation, or surgery.[1] |

| Tertiary | Hypothalamus | Results when the hypothalamus fails to produce sufficient thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). TRH prompts the pituitary gland to produce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Hence may also be termed hypothalamic-pituitary-axis hypothyroidism. |

General psychological associations

Hypothyroidism can be caused by lithium-based mood stabilizers, usually used to treat bipolar disorder (previously known as manic depression). In fact, lithium has occasionally been used to treat hyperthyroidism.[17]

In addition, patients with hypothyroidism and psychiatric symptoms may be diagnosed with:[18][19]

- Atypical depression (which may present as dysthymia)

- Bipolar spectrum syndrome (including bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, cyclothymia, or premenstrual syndrome)

- Inattentive ADHD or sluggish cognitive tempo

- Social Anxiety is also a symptom of Hypothyroidism.

Diagnosis

To diagnose primary hypothyroidism, many doctors simply measure the amount of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) being produced by the pituitary gland. High levels of TSH indicate that the thyroid is not producing sufficient levels of thyroid hormone (mainly as thyroxine (T4) and smaller amounts of triiodothyronine (T3)). However, measuring just TSH fails to diagnose secondary and tertiary hypothyroidism, thus leading to the following suggested blood testing if the TSH is normal and hypothyroidism is still suspected:

- Free triiodothyronine (fT3)

- Free levothyroxine (fT4)

- Total T3

- Total T4

Additionally, the following measurements may be needed:

- 24-Hour urine-free T3[20]

- Antithyroid antibodies — for evidence of autoimmune diseases that may be damaging the thyroid gland

- Serum cholesterol — which may be elevated in hypothyroidism

- Prolactin — as a widely available test of pituitary function

- Testing for anemia, including ferritin

- Basal body temperature

Treatment

Hypothyroidism is treated with the levorotatory forms of thyroxine (L-T4) and triiodothyronine (L-T3). Both synthetic and animal-derived thyroid tablets are available and can be prescribed for patients in need of additional thyroid hormone. Thyroid hormone is taken daily, and doctors can monitor blood levels to help assure proper dosing. There are several different treatment protocols in thyroid replacement therapy:

- T4 only

- This treatment involves supplementation of levothyroxine alone, in a synthetic form. It is currently the standard treatment in mainstream medicine.[21]

- T4 and T3 in combination

- This treatment protocol involves administering both synthetic L-T4 and L-T3 simultaneously in combination.[22]

- Desiccated thyroid extract

- Desiccated thyroid extract is an animal based thyroid extract, most commonly from a porcine source. It is also a combination therapy, containing natural forms of L-T4 and L-T3.[23]

Treatment controversy

A 2000 paper suggested "clear improvements in both cognition and mood" from combination therapy,[22] [24] and another in 2001 concluded that combined treatment seemed to be more effective than treatment with T4 alone on eight main symptoms of hypothyroidism.[23]

However, more recent studies have shown no improvement in mood or mental abilities for those on combination therapy, and possibly impaired well-being from subclinical hyperthyroidism.[25] Another 2006 study which looked at the correlation between free T3 and free T4 levels and psychological well-being in a randomized controlled trial of combined treatment found a strong correlation for free T4, but none for T3.[26]. A 2007 metaanalysis of the nine controlled studies so far published found no significant difference in the effect on psychiatric symptoms.[27].

In addition, a metaanalysis of 11 randomized controlled trials which looked at a wider range of symptoms including: bodily pain, anxiety, fatigue, body weight and a range of other factors, found no difference between the combined treatment and therapy with T4 alone.[28]

There is also concern among some practitioners about the use of T3 due to its short half-life. T3 when used on its own as a treatment results in wide fluctuations across the course of a day in the thyroid hormone levels, and with combined T3/T4 therapy there continues to be wide variation throughout each day.[29]

Subclinical hypothyroidism

Subclinical hypothyroidism occurs when thyrotropin (TSH) levels are elevated but thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) levels are normal.[13] Prevalence estimates range 3–8%, increasing with age; incidence is more common in women than in men.[30] In primary hypothyroidism, TSH levels are high and T4 and T3 levels are low. TSH usually increases when T4 and T3 levels drop. TSH prompts the thyroid gland to make more hormone. Hypothyroidism is sub-clinical if it has no discernible adverse effect on cellular metabolic rates (and ultimately the body's organs). The levels of the active hormones will be within the laboratory reference ranges. There is a range of opinion on the biochemical and symptomatic point at which to treat with levothyroxine, the typical treatment for overt hypothyroidism. Reference ranges have been debated as well. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (ACEE) considers 0.45–4.5 mIU/L, with the ranges down to 0.1 and up to 10 mIU/L requiring monitoring but not necessarily treatment.[31] There is always the risk of overtreatment and hyperthyroidism. Some studies have suggested that subclinical hypothyroidism does not need to be treated. A meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration found no benefit of thyroid hormone replacement except "some parameters of lipid profiles and left ventricular function."[32] A more recent metanalysis looking into whether subclinical hypothyroidism may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, as has been previously suggested,[33] found a possible modest increase and suggested further studies be undertaken with coronary heart disease as an end point "before current recommendations are updated."[34]

Alternative treatments

Alternative practitioners may combine conventional serum tests with less conventional tests to assess thyroid hormone function, or simply look at symptoms. Many have found that compounded slow release T3 used in combination with T4 may help to mitigate many of the symptoms of functional hypothyroidism and improve quality of life, although this is still controversial and is rejected by the conventional medical establishment.[35]

Alternative treatments for hypothyroidism consist of natural food and supplements which aid the thyroid or support the body by giving help where normally the thyroid would. An example of one natural treatment is coconut oil. The use of coconut oil has been proven in clinical studies to increase metabolism.[36]. Although it does not directly affect the thyroid, it aids the body's metabolism which has slowed down due to hypothyroidism.

See also

- Subacute lymphocytic thyroiditis

- Hyperthyroidism

- Risk factors in pregnancy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 American Thyroid Association (ATA) (2003) (PDF). Hypothyroidism Booklet. pp. 6. http://www.thyroid.org/patients/brochures/Hypothyroidism%20_web_booklet.pdf#search=%22hypothyroidism%22.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Hypothyroidism — primary — see list of Symptoms

- ↑ "Hypothyroidism — In-Depth Report." The New York Times. Copyright 2008

- ↑ "Hypothyroidism" (PDF). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. http://www.aace.com/pub/thyroidbrochures/pdfs/Hypothyroidism.pdf.

- ↑ Yeum CH, Kim SW, Kim NH, Choi KC, Lee J (July 2002). "Increased expression of aquaporin water channels in hypothyroid rat kidney". Pharmacol. Res. 46 (1): 85–8. doi:10.1016/S1043-6618(02)00036-1. PMID 12208125.

- ↑ Thyroid and Weight. The American Thyroid Association

- ↑ Samuels MH (October 2008). "Cognitive function in untreated hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism". Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 15 (5): 429–33. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32830eb84c (inactive 2009-12-05). PMID 18769215. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=1752-296X&volume=15&issue=5&spage=429.

- ↑ Neurologic manifestations of hypothyroidism Devon I Rubin, MD (Author), Michael J Aminoff, MD, Douglas S Ross, MD (Section Editors), Janet L Wilterdink, MD (Deputy Editor) – UpToDate.com, Last literature review version 17.3: September 2009; This topic last updated: March 18, 2009

- ↑ Hofeldt FD, Dippe S, Forsham PH (1972). "Diagnosis and classification of reactive hypoglycemia based on hormonal changes in response to oral and intravenous glucose administration" (PDF). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 25 (11): 1193–201. PMID 5086042. http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/reprint/25/11/1193.pdf.

- ↑ Jabbar A, Yawar A, Waseem S, et al. (May 2008). "Vitamin B12 deficiency common in primary hypothyroidism". J Pak Med Assoc 58 (5): 258–61. PMID 18655403.

- ↑ Cracking the Metabolic Code (Volume 1 of 2) by James B. Lavalle R.Ph. C.C.N. N.D, ISBN 1442950390, page 100

- ↑ Velázquez EM, Bellabarba Arata G (1997). "Effects of thyroid status on pituitary gonadotropin and testicular reserve in men". Arch. Androl. 38 (1): 85–92. doi:10.3109/01485019708988535. PMID 9017126.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Jack DeRuiter (2002) (PDF). Thyroid Pathology. pp. 30. http://www.auburn.edu/~deruija/endp_thyroidpathol.pdf.

- ↑ Brooks W (01/06/2008). "Hypothyroidism in Dogs". The Pet Health Library. VetinaryPartner.com. http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&A=461. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ↑ Simon H (2006-04-19). "Hypothyroidism". University of Maryland Medical Center. http://www.umm.edu/patiented/articles/what_causes_hypothyroidism_000038_2.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ↑ Department of Pathology (June 13, 2005). "Pituitary Gland -- Diseases/Syndromes". Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU). http://www.pathology.vcu.edu/education/endocrine/endocrine/pituitary/diseases.html. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ↑ Offermanns, Stefan; Rosenthal, Walter (2008). Encyclopedia of Molecular Pharmacology, Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 189. ISBN 9783540389163. http://books.google.com/?id=iwwo5gx8aX8C&pg=PA189&dq=propylthiouracil+1940s&q.

- ↑ Heinrich TW, Grahm G (2003). "Hypothyroidism Presenting as Psychosis: Myxedema Madness Revisited". Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry 5 (6): 260–6. doi:10.4088/PCC.v05n0603. PMID 15213796.

- ↑ Geracioti TD (2006). "Identifying Hypothyroidism’s Psychiatric Presentations". Current Psychiatry 5 (11): 98–117. http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=4570.

- ↑ Baisier WV, Hertoghe J, Eeckhaut W (June 2000). "Thyroid insufficiency. Is TSH the only diagnostic tool?". J Nutr Environ Med 10 (2): 105–13. doi:10.1080/13590840050043521. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/routledg/cjne/2000/00000010/00000002/art00002.

- ↑ American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (November/December 2002). "Medical Guidelines For Clinical Practice For The Evaluation And Treatment Of Hyperthyroidism And Hypothyroidism" (PDF). Endocrine Practice 8 (6): 457–469. PMID 15260011. http://www.aace.com/pub/pdf/guidelines/hypo_hyper.pdf.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bunevicius R, Kazanavicius G, Zalinkevicius R, Prange AJ (February 1999). "Effects of thyroxine as compared with thyroxine plus triiodothyronine in patients with hypothyroidism". N. Engl. J. Med. 340 (6): 424–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902113400603. PMID 9971866. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/340/6/424.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Baisier, W.V.; Hertoghe, J.; Eeckhaut, W. (September 2001). "Thyroid Insufficiency. Is Thyroxine the Only Valuable Drug?". Journal of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine 11 (3): 159–66. doi:10.1080/13590840120083376. — Abstract

- ↑ Robertas Bunevicius, Arthur J. Prange Jr. (June 2000). "Mental improvement after replacement therapy with thyroxine plus triiodothyronine: relationship to cause of hypothyroidism". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 3 (2): 167–174. doi:10.1017/S1461145700001826. PMID 11343593. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?aid=52289.

- ↑ Siegmund W, Spieker K, Weike AI, et al. (June 2004). "Replacement therapy with levothyroxine plus triiodothyronine (bioavailable molar ratio 14 : 1) is not superior to thyroxine alone to improve well-being and cognitive performance in hypothyroidism". Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 60 (6): 750–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02050.x. PMID 15163340.

- ↑ Ponnusamy Saravanan, Theo J. Visser and Colin M. Dayan (2006). "Psychological Well-Being Correlates with Free Thyroxine But Not Free 3,5,3'-Triiodothyronine Levels in Patients on Thyroid Hormone Replacement". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 91 (9): 3389–3393. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0414. PMID 16804044.

- ↑ Joffe RT, Brimacombe M, Levitt AJ, Stagnaro-Green A (2007). "Treatment of clinical hypothyroidism with thyroxine and triiodothyronine: a literature review and metaanalysis". Psychosomatics 48 (5): 379–84. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.379. PMID 17878495.

- ↑ Simona Grozinsky-Glasberg, Abigail Fraser, Ethan Nahshoni, Abraham Weizman and Leonard Leibovici (2006). "Thyroxine-Triiodothyronine Combination Therapy Versus Thyroxine Monotherapy for Clinical Hypothyroidism: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 91 (7): 2592–2599. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0448. PMID 16670166.

- ↑ Saravanan P, Siddique H, Simmons DJ, Greenwood R, Dayan CM (April 2007). "Twenty-four hour hormone profiles of TSH, Free T3 and free T4 in hypothyroid patients on combined T3/T4 therapy". Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 115 (4): 261–7. doi:10.1055/s-2007-973071. PMID 17479444.

- ↑ Fatourechi V (2009). "Subclinical hypothyroidism: an update for primary care physicians". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 84 (1): 65–71. doi:10.4065/84.1.65. PMID 19121255.

- ↑ "Subclinical Thyroid Disease". Guidelines & Position Statements. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. July 11, 2007. http://www.aace.com/pub/positionstatements/subclinical.php. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ↑ Villar H, Saconato H, Valente O, Atallah A (2007). "Thyroid hormone replacement for subclinical hypothyroidism". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003419. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003419.pub2. PMID 17636722.

- ↑ Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, Fazio S (December 2002). "Effects of subclinical thyroid dysfunction on the heart". Ann. Intern. Med. 137 (11): 904–14. PMID 12458990.

- ↑ Ochs N, Auer R, Bauer DC, et al. (June 2008). "Meta-analysis: subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk for coronary heart disease and mortality". Ann. Intern. Med. 148 (11): 832–45. PMID 18490668. http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/148/11/832.

- ↑ Todd CH (Ded 2009). "Management of thyroid disorders in primary care: challenges and controversies". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 85 (1010): 655–9. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2008.077701. PMID 20075403. http://pmj.bmj.com/content/85/1010/655.long.

- ↑ Hill,Peters. Thermogenesis in humans during overfeeding with medium-chain triglycerides.. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2739575?dopt=Abstract.

Further reading

- Tchong L, Veloski C, Siraj ES (May 2009). "Hypothyroidism: management across the continuum". J Clin Outcomes Manage 16 (5): 231–5. http://www.temple.edu/imreports/Reading/Endo%20-%20Hypothyroid.pdf.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||