Osteosarcoma

| Osteosarcoma | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

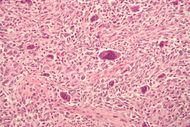

Micrograph of an osteosarcoma with multinucleated giant osteoclast-like cells. H&E stain. |

|

| ICD-10 | C40.-C41. |

| ICD-9 | 170 |

| ICD-O: | M9180/3 |

| OMIM | 259500 |

| DiseasesDB | 9392 |

| MedlinePlus | 001650 |

| eMedicine | ped/1684 orthoped/531 radio/504 radio/505 |

| MeSH | D012516 |

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive cancerous neoplasm arising from primitive transformed cells of mesenchymal origin that exhibit osteoblastic differentiation and produce malignant osteoid. It is the most common histological form of primary bone cancer.[1]

Contents |

Incidence

Osteosarcoma is the eighth most common form of childhood cancer, comprising 2.4% of all malignancies in pediatric patients, and approximately 20% of all bone cancers.[1]

Incidence rates for osteosarcoma in U.S. patients under 20 years of age are estimated at 5.0 per million per year in the general population, with a slight variation between individuals of black, Hispanic, and white ethnicities (6.8, 6.5, and 4.6 per million per year, respectively. It is slightly more common in males (5.4 per million per year) than in females (4.0 per million per year).[1]

There is a preference for origination in the metaphyseal region of tubular long bones, with 42% occurring in the femur, 19% in the tibia, and 10% in the humerus. About 8% of all cases occur in the skull and jaw, and another 8% in the pelvis.[1]

Prevalence

Osteogenic sarcoma is the sixth leading cancer in children under age 15. Osteogenic sarcoma affects 400 children under age 20 and 500 adults (most between the ages of 15-30) every year in the USA. Approximately 1/3 of the 900 will die each year, or about 300 a year. A second peak in incidence occurs in the elderly, usually associated with an underlying bone pathology such as Paget's disease, medullary infarct, or prior irradiation.

Treatment

Complete radical surgical en bloc resection is the treatment of choice in osteosarcoma.[1]

Although about 90% of patients are able to have limb-salvage surgery, complications, such as infection, prosthetic loosening and non-union, or local tumor recurrence may cause the need for further surgery or amputation.

Mortality and Survival

Deaths due to malignant neoplasms of the bones and joints account for about**** all childhood cancer deaths.[1]

Mortality rates due to osteosarcoma have recently been declining at approximately 1.3% per year.[1] Current long-term survival probabilities for osteosarcoma have improved dramatically in recent decades and now approximate 68%.[1]

Pathology

The tumour may be localised at the end of the long bone. Most often it affects the upper end of tibia or humerus, or lower end of femur. Osteosarcoma tends to affect regions around the knee in 60% of cases, 15% around the hip, 10% at the shoulder, and 8% in the jaw. The tumor is solid, hard, irregular ("fir-tree," "moth-eaten" or "sun-burst" appearance on X-ray examination) due to the tumor spicules of calcified bone radiating in right angles. These right angles form what is known as Codman's triangle. Surrounding tissues are infiltrated.

Microscopically: The characteristic feature of osteosarcoma is presence of osteoid (bone formation) within the tumour. Tumor cells are very pleomorphic (anaplastic), some are giant, numerous atypical mitoses. These cells produce osteoid describing irregular trabeculae (amorphous, eosinophilic/pink) with or without central calcification (hematoxylinophilic/blue, granular) - tumor bone. Tumor cells are included in the osteoid matrix. Depending on the features of the tumour cells present (whether they resemble bone cells, cartilage cells or fibroblast cells), the tumour can be subclassified. Osteosarcomas may exhibit multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells.[2]

Causes

The causes of osteosarcoma are not known. It may be hurt in bone. Several research groups are investigating cancer stem cells and their potential to cause tumors.[3] The connection between osteosarcoma and fluoride has been investigated; there is no clear association between water fluoridation and deaths due to osteosarcoma.[4] Radiotherapy for unrelated conditions may be a rare cause.[5]

Symptoms

Many patients first complain of pain that may be worse at night, and may have been occurring for some time. If the tumor is large, it can appear as a swelling. The affected bone is not as strong as normal bones and may fracture with minor trauma (a pathological fracture).

Diagnosis

Family physicians and orthopedists rarely see a malignant bone tumor (most bone tumors are benign). Thus, many patients are initially misdiagnosed with cysts or muscle problems, and some are sent straight to physical therapy without an x-ray.

The route to osteosarcoma diagnosis usually begins with an x-ray, continues with a combination of scans (CT scan, PET scan, bone scan, MRI) and ends with a surgical biopsy. Films are suggestive, but bone biopsy is the only definitive method to determine whether a tumor is malignant or benign.

The biopsy of suspected osteosarcoma should be performed by a qualified orthopedic oncologist. The American Cancer Society states: "Probably in no other cancer is it as important to perform this procedure properly. An improperly performed biopsy may make it difficult to save the affected limb from amputation."

Treatment

Patients with osteosarcoma are best managed by a medical oncologist and an orthopedic oncologist experienced in managing sarcomas. Current standard treatment is to use neoadjuvant chemotherapy (chemotherapy given before surgery) followed by surgical resection. The percentage of tumor cell necrosis (cell death) seen in the tumor after surgery gives an idea of the prognosis and also lets the oncologist know if the chemotherapy regime should be altered after surgery.

Standard therapy is a combination of limb-salvage orthopedic surgery when possible (or amputation in some cases) and a combination of high dose methotrexate with leucovorin rescue, intra-arterial cisplatin, adriamycin, ifosfamide with mesna, BCD, etoposide, muramyl tri-peptite (MTP). Rotationplasty is also another surgical technique that may be used. Ifosfamide can be used as an adjuvant treatment if the necrosis rate is low.

Despite the success of chemotherapy for osteosarcoma, it has one of the lowest survival rates for pediatric cancer. The best reported 10-year survival rate is 92%; the protocol used is an aggressive intra-arterial regimen that individualizes therapy based on arteriographic response.[6] Three-year event free survival ranges from 50% to 75%, and five-year survival ranges from 60% to 85+% in some studies. Overall, 65-70% patients treated five years ago will be alive today [7]. These survival rates are overall averages and vary greatly depending on the individual necrosis rate.

Fluids are given for hydration, while drugs like Kytril and Zofran help with nausea and vomiting. Neupogen, Neulasta help with white blood cell counts and neutrophil counts. Blood transfusions and [(epogen)] help with anemia.

Prognosis

Prognosis is separated into three groups.

- Stage I osteosarcoma is rare and includes parosteal osteosarcoma or low-grade central osteosarcoma. It has an excellent prognosis (>90%) with wide resection.

- Stage IIb prognosis depends on the site of the tumor (proximal tibia, femur, pelvis, etc.) size of the tumor mass (in cm.), and the degree of necrosis from neoadjuvant chemotherapy (chemotherapy prior to surgery). Other pathological factors such as the degree of p-glycoprotein, whether the tumor is cxcr4-positive [8], or Her2-positive are also important, as these are associated with distant metastases to the lung. The prognosis for patients with metastatic osteosarcoma improves with longer times to metastases, (more than 12 months-24 months), a smaller number of metastases (and their resectability). It is better to have fewer metastases than longer time to metastases. Those with a longer length of time(>24months) and few nodules (2 or fewer) have the best prognosis with a 2-year survival after the metastases of 50% 5-year of 40% and 10 year 20%. If metastases are both local and regional, the prognosis is worse.

- Initial presentation of stage III osteosarcoma with lung metastates depends on the resectability of the primary tumor and lung nodules, degree of necrosis of the primary tumor, and maybe the number of metastases. Overall prognosis is about 30% [9].

Canine osteosarcoma

Risk factors

Osteosarcoma is the most common bone tumor in dogs and typically afflicts middle-age large and giant breed dogs such as Irish Wolfhounds, Greyhounds, German Shepherds, Rottweilers, Doberman Pinschers and Great Danes. It has a ten times greater incidence in dogs than humans.[10] A hereditary base has been shown in St. Bernard dogs.[11] Spayed/neutered dogs have twice the risk of intact ones to develop osteosarcoma.[12] Infestation with the parasite Spirocerca lupi can cause osteosarcoma of the esophagus.[13]

Clinical presentation

The most commonly affected bones are the proximal humerus, the distal radius, the distal femur, and the tibia,[14] following the basic premise "far from the elbow, close to the knee". Other sites include the ribs, the mandible, the spine, and the pelvis. Rarely, osteosarcoma may arise from soft-tissues (extraskeletal osteosarcoma). Metastasis of tumors involving the limb bones is very common, usually to the lungs. The tumor causes a great deal of pain, and can even lead to fracture of the affected bone. As with human osteosarcoma, bone biopsy is the definitive method to reach a final diagnosis. Osteosarcoma should be differentiated from other bone tumours and a range of other lesions, such as osteomyelitis. Differential diagnosis of the osteosarcoma of the skull in particular includes, among others, chondrosarcoma and the multilobular tumour of bone[15][16].

Treatment and prognosis

Amputation of the leg is the initial treatment, although this alone will not prevent metastasis. Chemotherapy combined with amputation improves the survival time, but most dogs still die within a year.[14] There are surgical techniques designed to save the leg (limb-sparing procedures), but they do not improve the prognosis. One key difference between osteosarcoma in dogs and humans is that the cancer is far more likely to spread to the lungs in dogs.

Some current studies indicate that osteoclast inhibitors such as alendronate and pamidronate may have beneficial effects on the quality of life by reducing osteolysis, thus reducing the degree of pain as well as the risk of pathological fractures.[17]

Experimental laser procedure

Autologous patient specific tumor antigen response (apSTAR Veterinary Cancer Laser System: The use of a laser combined with a polymer has been shown to enhance tumor immunity and improve the rate of primary and metastatic tumor regression in laboratory models of tumors. IMULAN BioTherapeutics, LLC has recently started examining the use of this laser device, termed apSTAR, for dogs with osteosarcoma and other tumor types.[18]

Osteosarcoma in cats

Osteosarcoma is also the most common bone tumor in the cat, although not as frequently encountered, and most typically affects the rear legs. The cancer is less aggressive in cats than in dogs, and therefore amputation alone can lead to a significant survival time.[14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res 2010;152:3-13.

- ↑ Papalas JA, Balmer NN, Wallace C, Sangüeza OP (June 2009). "Ossifying dermatofibroma with osteoclast-like giant cells: report of a case and literature review". Am J Dermatopathol 31 (4): 379–83. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181966747. PMID 19461244.

- ↑ Osuna D, de Alava E (2009). "Molecular pathology of sarcomas". Rev Recent Clin Trials 4 (1): 12–26. PMID 19149759.

- ↑ National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) (2007). "A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation" (PDF). http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/PUBLICATIONS/synopses/_files/eh41.pdf. Retrieved 2009-02-24. Summary: Yeung CA (2008). "A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation". Evid Based Dent 9 (2): 39–43. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400578. PMID 18584000. Lay summary – NHMRC (2007).

- ↑ Dhaliwal J, Sumathi VP and Grimer RJ. Radiation-induced periosteal osteosarcoma. Grand Rounds 10: 13-18 [1]

- ↑ Wilkins RM, Cullen JW, Odom L, Jamroz BA, Cullen PM, Fink K, Peck SD, Stevens SL, Kelly CM, Camozzi AB: Superior survival in treatment of primary non-metastatic pediatric osteosarcoma of the extremity. Ann Surg Oncol 10:498-507, 2003.

- ↑ Buecker, PJ, Gebhardt, M and Weber, K (2005). "Osteosarcoma". ESUN. http://sarcomahelp.org/osteosarcoma.html. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ http://www.osteosarcomasupport.org/cxcr4_metastases.pdf

- ↑ Koshkina, NV and Corey, S (2008). "Novel Targets to Treat Osteosarcoma Lung Metastases". ESUN. http://sarcomahelp.org/research_center/osteosarcoma_lung_metastases.html. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ Withrow, S.J. (2003). "Limb Sparing Trials and Canine Osteosarcoma". Genes, Dogs and Cancer: 3rd Annual Canine Cancer Conference, 2003. http://www.ivis.org/proceedings/Keystone/2003/withrow/chapter_frm.asp?LA=1. Retrieved 2006-06-16.

- ↑ Bech-Nielsen, S., Haskins, M. E. et al. (1978). "Frequency of osteosarcoma among first-degree relatives of St. Bernard dogs". J Natl Cancer Inst 60(2):349-53.

- ↑ Ru, B., Terracini, G. et al. (1998). "Host related risk factors for canine osteosarcoma". Vet J 156(1):31-9 156: 31. doi:10.1016/S1090-0233(98)80059-2.

- ↑ Ranen E, Lavy E et al. (2004). "Spirocercosis-associated esophageal sarcomas in dogs. A retrospective study of 17 cases (1997-2003)". Vet Parasitol 119(2-3):209-21 119: 209. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.10.023.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Morrison, Wallace B. (1998). Cancer in Dogs and Cats (1st ed.). Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-06105-4.

- ↑ Loukopoulos P, Thornton JR , Robinson WF. Clinical and pathologic relevance of p53 index in canine osseous tumors. Veterinary Pathology 2003; 40:237-248

- ↑ Psychas V, Loukopoulos P, Polizopoulou ZS , Sofianidis G. Multilobular tumour of the caudal cranium causing severe cerebral and cerebellar compression in a dog. Journal of Veterinary Science 2009; 10:81-83.

- ↑ Tomlin, J. L., Sturgeon, C. et al. (2000). "Use of the bisphosphonate drug alendronate for palliative management of osteosarcoma in two dogs". Vet Rec 147(5):129-32.

- ↑ [2]

Further reading

- James, H. (1979). Promises in the Dark. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-13453-1. Story of a young girl's osteosarcoma fight and its effect on her relationship with her boyfriend

- Trottier, Maxine (2005). Terry Fox: A Story of Hope. Markham, Ont: Scholastic Canada. ISBN 0-439-94888-6. About Terry Fox and his quest to raise $25 million for cancer research by running across Canada on his prosthetic leg. Also The Terry Fox Story, a 1983 movie.

- Belshaw, Sheila M. (2001). Fly With a Miracle. Denor Press. ISBN 0 9526056 7 8. The story of a family's journey through teenage osteosarcoma and its aftermath.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||