Skin neoplasm

| Skin cancer | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

A basal cell carcinoma. Note the pearly appearance and telangiectasia. |

|

| ICD-10 | C43.-C44. |

| ICD-9 | 172, 173 |

| ICD-O: | 8010-8720 |

| MeSH | D012878 |

Skin neoplasms are growths on the skin which can have many causes. The three most common skin cancers are basal cell cancer, squamous cell cancer, and melanoma, each of which is named after the type of skin cell from which it arises. Skin cancer generally develops in the epidermis (the outermost layer of skin), so a tumor is usually clearly visible. This makes most skin cancers detectable in the early stages. Unlike many other cancers, including those originating in the lung, pancreas, and stomach, only a small minority of those afflicted will actually die of the disease.[1]. In fact, though it can be disfiguring, except for melanoma, skin cancer is rarely fatal. Skin cancer represents the most commonly diagnosed cancer, surpassing lung, breasts, colorectal, and prostate cancer.[1] Melanoma is less common than basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, but it is the most serious—for example, in the UK there are 9,500 new cases of melanoma each year, and 2,300 deaths.[2] It is the most common cancer in the young population (20 – 39 age group).[3] Most cases are caused by long periods of exposure to the sun[3]. Non-melanoma skin cancers are the most common skin cancers. The majority of these are basal cell carcinomas. These are usually localized growths caused by excessive cumulative exposure to the sun and do not tend to spread.

Contents |

Classification

The three most common types of skin cancers are:

| Cancer | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| Basal cell carcinoma | Note the fleshy color, symmetrical nature, and ulceration which are characteristic. |

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Commonly presents as a red, crusted, or scaly patch. |

|

| Malignant melanoma | The common appearance is an asymmetrical area, with an irregular border, color variation, and greater than 6 mm diameter.[4] |

|

Basal cell carcinomas are present on sun-exposed areas of the skin, especially the face. They rarely metastasize and rarely cause death. They are easily treated with surgery or radiation. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) are common, but much less common than basal cell cancers. They metastasize more frequently than BCCs. Even then, the metastasis rate is quite low, with the exception of SCCs of the lip, ear, and in immunosuppressed patients. Melanomas are the least frequent of the 3 common skin cancers. They frequently metastasize, and are deadly once spread.

Less common skin cancers include: Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, Merkel cell carcinoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, keratoacanthoma, spindle cell tumors, sebaceous carcinomas, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, Pagets's disease of the breast, atypical fibroxanthoma, leimyosarcoma, and angiosarcoma

The BCC and the SCC often carry a UV-signature mutation indicating that these cancers are caused by UV-B radiation via the direct DNA damage. However the malignant melanoma is predominantly caused by UV-A radiation via the indirect DNA damage. The indirect DNA damage is caused by free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Research indicates that the absorption of three sunscreen ingredients into the skin, combined with a 60-minute exposure to UV, leads to an increase of free radicals in the skin, if applied in too little quantities and too infrequently.[5] However, the researchers add that newer creams often do not contain these specific compounds, and that the combination of other ingredients tends to retain the compounds on the surface of the skin. They also add the frequent re-application reduces the risk of radical formation.

Skin cancer as a group

The three main types of cancer are not similar and basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and malignant melanoma cannot be viewed as skin cancer.

- the mechanism that generates the first two forms is different from the mechanism that generates the melanoma. The direct DNA damage is responsible for BCC and SCC while the indirect DNA damage causes melanoma.

- the mortality rate of BCC and SCC is around 0.3% causing 2000 deaths per year in the US. In comparison the mortality rate of melanoma is 15-20% and it causes 6500 deaths per year.[6]:29,31

Even though it is much less common than BCCs and SCCs, malignant melanoma is responsible for 75% of all skin cancer-related deaths.[7]

While sunscreen has been shown to protect against BCC and SCC it may not protect against malignant melanoma. When sunscreen penetrates into the skin it generates reactive chemicals[5]. It has been found that sunscreen use is correlated with malignant melanoma.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Experimental and the epidemiological evidence suggests that sunscreen use correlates with melanoma incidence. This gives rise to questions regarding the possibility that a sunscreen user's lifetime exposure to ultraviolet light may be higher than average. Alternatively, one might question whether sun screens are themselves tumor promoters or carcinogens. Arguably, sunscreen users are the ones most likely to be burned or have been burned by sun light. Similarly, most sunscreens primarily screen UVB, the primary cause of sunburn, while UVA is the primary cause of melanoma. Thus, by limiting the discomfort of sunburn, UVB screening may indirectly result in more UVA exposure. In any case, if some sunscreens promote skin cancer, physical light-scattering sunscreens based in zinc oxide, titanium dioxide or some other natural base are likely safer than chemical blockers such as benzones, etc., as they will be less chemically active. [14]

Signs and symptoms

There are a variety of different skin cancer symptoms. These include changes in the skin that do not heal, ulcering in the skin, discolored skin, and changes in existing moles, such as jagged edges to the mole and enlargement of the mole.

- Basal cell carcinoma usually presents as a raised, smooth, pearly bump on the sun-exposed skin of the head, neck or shoulders. Sometimes small blood vessels can be seen within the tumor. Crusting and bleeding in the center of the tumor frequently develops. It is often mistaken for a sore that does not heal. This form of skin cancer is the least deadly and with proper treatment can be completely eliminated, often without scarring.

- Squamous cell carcinoma is commonly a red, scaling, thickened patch on sun-exposed skin. Some are firm hard nodules and dome shaped like keratoacanthomas. Ulceration and bleeding may occur. When SCC is not treated, it may develop into a large mass. Squamous cell is the second most common skin cancer. It is dangerous, but not nearly as dangerous as a melanoma.

- Most melanomas are brown to black looking lesions. Unfortunately, a few melanomas are pink, red or fleshy in color; these are called amelanotic melanomas. These tend to be more aggressive. Warning signs of malignant melanoma include change in the size, shape, color or elevation of a mole. Other signs are the appearance of a new mole during adulthood or new pain, itching, ulceration or bleeding. An often-used mnemonic is "ABCD", where A= asymmetrical, B= "borders" ( irregular= "Coast of Main sign" ), C= "color" ( variegated ) and D= "diameter" ( larger than 6 mm --the size of a pencil eraser).

- Merkel cell carcinomas are most often rapidly growing, non-tender red, purple or skin colored bumps that are not painful or itchy. They may be mistaken for a cyst or other type of cancer.[15]

Causes

Skin cancer has many potential causes. Examples include:

- Smoking tobacco and related products can double the risk of skin cancer.[16][17]

- Overexposure to UV-radiation may cause skin cancer either via the direct DNA damage or via the indirect DNA damage mechanism. Overexposure (burning) UVA & UVB have both been implicated in causing DNA damage resulting in cancer. Because UVB is highly absorbed by the atmosphere, UVB between 10AM and 4PM is most intense. Natural (sun) & artificial UV exposure (tanning salons) are possibly associated with skin cancer.[18]

- UVB rays primarily affect the epidermis causing sunburns, redness, and blistering of the skin when overexposed. The melanin of the epidermis is activated with UVB just as with UVA; however, the effects are longer lasting with pigmentation continuing over 24 hours.

- Chronic non-healing wounds, especially burns. These are called Marjolin's ulcers based on their appearance, and can develop into squamous cell carcinoma.

- Genetic predisposition, including "Congenital Melanocytic Nevi Syndrome". CMNS is characterized by the presence of "nevi" or moles of varying size that either appear at or within 6 months of birth. Nevi larger than 20 mm (3/4") in size are at higher risk for becoming cancerous.

- Human papilloma virus (HPV) is often associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the genitals, anus, mouth, pharynx, and fingers.

- Skin cancer is one of the potential dangers of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation.

- Deficiencies in certain vitamins and minerals.

- Arsenic poisoning is associated with an increased incidence of squamous cell carcinoma.

A 2010 study has found a relation between HPV infection and incidence of squamous cell carcinoma.[19]

Prevention

Although it is impossible to completely eliminate the possibility of skin cancer, the risk of developing such a cancer can be reduced significantly with the following steps:

- Avoid the use of tobacco products.

- Reducing overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, especially in early years

- Avoiding sun exposure during the peak UV times during the day, typically from 10 AM to 3 PM (dependent on country) when the sun is directly over head

- Wearing protective clothing (long sleeves and hats) when outdoors

- Using a broad-spectrum sunscreen that blocks both UVA and UVB radiation

- Reapply sun block as per the manufacturers directions

Australian scientist Ian Frazer who developed a vaccine for cervical cancer, says that a vaccine effective in preventing for certain types of skin cancer has proven effective on animals and could be available within a decade. The vaccine would only be effective against Squamous Cell Carcinoma.[20]

Primary health care providers should examine their patients during the course of a routine comprehensive physical examination by means of a full body screening (all areas of the body's skin surface are examined, with the use of a special light and a magnifying glass, for abnormal masses, lesions, and cancerous neoplasms like BCC, SCC, and MM). Referrals or visits to a dermatologist will usually include this as a first part of the examination. Many times, hospitals, doctor's offices, and dermatologist's offices will perform these for the general public as part of a mass screening program done at certain times during the year, and these are usually free or are low-priced and thus are often very popular. If necessary, skin cells from the outer epidermis can be scraped off or an actual biopsy performed, and the results examined for pathologies.

Pathology

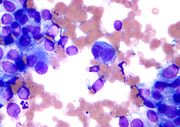

Squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor which originates in epidermis, squamous mucosa or areas of squamous metaplasia.

Macroscopically, the tumor is often elevated, fungating, or may be ulcerated with irregular borders. Microscopically, tumor cells destroy the basement membrane and form sheets or compact masses which invade the subjacent connective tissue (dermis). In well differentiated carcinomas, tumor cells are pleomorphic/atypical, but resembling normal keratinocytes from prickle layer (large, polygonal, with abundant eosinophilic (pink) cytoplasm and central nucleus). Their disposal tends to be similar to that of normal epidermis: immature/basal cells at the periphery, becoming more mature to the centre of the tumor masses. Tumor cells transform into keratinized squamous cells and form round nodules with concentric, laminated layers, called "cell nests" or "epithelial/keratinous pearls". The surrounding stroma is reduced and contains inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes). Poorly differentiated squamous carcinomas contain more pleomorphic cells and no keratinization.[21]

Management

Treatment is dependent on type of cancer, location of the cancer, age of the patient, and whether the cancer is primary or a recurrence. One should look at the specific type of skin cancer (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or melanoma) of concern in order to determine the correct treatment required. An example would be a small basal cell cancer on the cheek of a young man, where the treatment with the best cure rate (Mohs surgery or CCPDMA) might be indicated. In the case of an elderly frail man with multiple complicating medical problems, a difficult to excise basal cell cancer of the nose might warrant radiation therapy (slightly lower cure rate) or no treatment at all. Topical chemotherapy might be indicated for large superficial basal cell carcinoma for good cosmetic outcome, whereas it might be inadequate for invasive nodular basal cell carcinoma or invasive squamous cell carcinoma.. In general, melanoma is poorly responsive to radiation or chemotherapy.

For low-risk disease, radiation therapy (external beam radiotherapy or brachytherapy), topical chemotherapy (imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil) and cryotherapy (freezing the cancer off) can provide adequate control of the disease; both, however, may have lower overall cure rates than certain type of surgery. Other modalities of treatment such as photodynamic therapy, topical chemotherapy, electrodessication and curettage can be found in the discussions of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Mohs' micrographic surgery (Mohs surgery) is a technique used to remove the cancer with the least amount of surrounding tissue and the edges are checked immediately to see if tumor is found. This provides the opportunity to remove the least amount of tissue and provide the best cosmetically favorable results. This is especially important for areas where excess skin is limited, such as the face. Cure rates are equivalent to wide excision. Special training is required to perform this technique. An alternative method is CCPDMA and can be performed by a pathologist not familiar with Mohs surgery.

In the case of disease that has spread (metastasized), further surgical procedures or chemotherapy may be required.[22]

Scientists have recently been conducting experiments on what they have termed "immune- priming". This therapy is still in its infancy but has been shown to effectively attack foreign threats like viruses and also latch onto and attack skin cancers. More recently researchers have focused their efforts on strengthening the body's own naturally produced "helper T cells" that identify and lock onto cancer cells and help guide the killer cells to the cancer. Researchers infused patients with roughly 5 billion of the helper T cells without any harsh drugs or chemotherapy. This type of treatment if shown to be effective has no side effects and could change the way cancer patients are treated.[23]

A cream used to treat pre-cancerous skin lesions also reverses signs of aging, a study released in April 2009 indicated.[24] In March 2010 academics from Dundee University in Scotland announced they had devised a new, less-painful method of treating skin cancer, which could be administered from the home.[25]

Post surgery reconstruction

Currently, surgical excision is the most common form of treatment for skin cancers. The goal of reconstructive surgery is restoration of normal appearance and function. The choice of technique in reconstruction is dictated by the size and location of the defect. Excision and reconstruction of facial skin cancers is generally more challenging due to presence of highly visible and functional anatomic structures in the face.

When skin defects are small in size, most can be repaired with simple repair where skin edges are approximated and closed with sutures. This will result in a linear scar. If the repair is made along a natural skin fold or wrinkle line, the scar will be hardly visible. Larger defects may require repair with a skin graft, local skin flap, pedicled skin flap, or a microvascular free flap. Skin grafts and local skin flaps are by far more common than the other listed choices.

Skin grafting is patching of a defect with skin that is removed from another site in the body. The skin graft is sutured to the edges of the defect, and a bolster is placed atop the graft for seven to ten days, to immobilize the graft as it heals in place. There are two forms of skin grafting: split thickness and full thickness. In a split thickness skin graft, a shaver is used to shave a layer of skin from the abdomen or thigh. The donor site, regenerates skin and heals over a period of two weeks. In a full thickness skin graft, a segment of skin is totally removed and the donor site needs to be sutured closed.[26] Split thickness grafts can be used to repair larger defects, but the grafts are inferior in their cosmetic appearance. Full thickness skin grafts are more acceptable cosmetically. However, full thickness grafts can only be used for small or moderate sized defects.

Local skin flaps are a method of closing defects with tissue that closely matches the defect in color and quality. Skin from the periphery of the defect site is mobilized and repositioned to fill the deficit. Various forms of local flaps can be designed to minimize disruption to surrounding tissues and maximize cosmetic outcome of the reconstruction. Pedicled skin flaps are a method of transferring skin with an intact blood supply from a nearby region of the body. An example of such reconstruction is a pedicled forehead flap for repair of a large nasal skin defect. Once the flap develops a source of blood supply form its new bed, the vascular pedicle can be detached.[27]

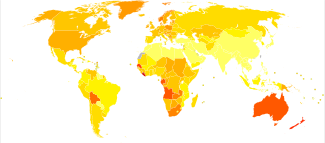

Epidemiology

A study of the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer from 1992 to 2006 in the United States was performed by the dermatologist Howard Rogers, MD, PhD, and his colleagues based on the evaluation of Medicare databases. The results of their research showed that cases of non-melanoma skin cancer rose an average of 4.2% a year. [29]

More than 3.5 million cases of skin cancer are diagnosed annually in the United States, which makes it the most common form of cancer in that country. According to the Skin Cancer Foundation, one in five Americans will develop skin cancer at some point of their lives. The first most common form of skin cancer is basal cell carcinoma, followed by the squamous cell carcinoma. Although the incidence of many cancers in the United States is falling, the incidence of melanoma keeps growing, with approximately 68,729 melanomas diagnosed in 2004 according to reports of the National Cancer Institute. [30]

The survival rate for patients with melanoma depends upon when they start treatment. The cure rate is very high when melanoma is detected in early stages, when it can easily be removed surgically. The prognosis is less favorable if the melanoma has spread to other parts of the body. [31]

In the UK, 84,500 non-melanoma skin cancers were registered in 2007 although a study estimated that at least 100,000 cases are diagnosed each year. Most NMSCs were basal cell carcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas. In 2007, 10,672 cases of malignant melanoma were diagnosed. [32]

According to the British Association of Dermatologists children, from 0 to 14 years, and teenagers, from 15 to 19 years, exhibit the highest rates of skin cancers of any European country. Furthermore, incidence of melanoma increased four times in UK teenagers from 1978 to 1997. [33]

Australia exhibits one of the highest rates of skin cancer incidence in the world, almost four times the rates registered in the United States, the UK and Canada. Around 434,000 people receive treatment for non-melanoma skin cancers and 10,300 are treated for melanoma. Melanoma is the common type of cancer in people between 15- 44 years in Australia. [34]

See also

- Mohs surgery and CCPDMA

- Skin biopsy

- Sun protective clothing

- Sunscreen controversy

- Risks and benefits of sun exposure

- List of cutaneous conditions

- External beam radiotherapy

- Brachytherapy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 National Cancer Institute - Common Cancer Types (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/commoncancers)

- ↑ "Mutation 'sparks most melanoma'". BBC News. 2009-04-07. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/7985323.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/top-stories/2009/04/08/skin-cancer-killing-sunbed-generation-115875-21262348/

- ↑ "Malignant Melanoma: eMedicine Dermatology". http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100753-overview.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hanson Kerry M.; Gratton Enrico; Bardeen Christopher J. (2006). "Sunscreen enhancement of UV-induced reactive oxygen species in the skin". Free Radical Biology and Medicine 41 (8): 1205–1212. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.011. PMID 17015167.

- ↑ C. C. Boring, T. S. Squires and T. Tong (1991). "Cancer statistics, 1991". SA Cancer Journal for Clinician 41: 19–36. doi:10.3322/canjclin.41.1.19. http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/reprint/41/1/19.pdf.

- ↑ "Early Detection and Treatment of Skin Cancer". American Family Physician. July 2000. ISBN 0962768804. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000715/357.html. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ Garland C, Garland F, Gorham E (1992). "Could sunscreens increase melanoma risk?". Am J Public Health 82 (4): 614–5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.82.4.614. PMID 1546792. PMC 1694089. http://www.ajph.org/cgi/reprint/82/4/614.

- ↑ Westerdahl J; Ingvar C; Masback A; Olsson H (2000). "Sunscreen use and malignant melanoma.". International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 87 (1): 145–50. doi:10.1002/1097-0215(20000701)87:1<145::AID-IJC22>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 10861466.

- ↑ Autier P; Dore J F; Schifflers E; et al. (1995). "Melanoma and use of sunscreens: An EORTC case control study in Germany, Belgium and France". Int. J. Cancer 61 (6): 749–755. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910610602. PMID 7790106.

- ↑ Weinstock, M. A. (1999). "Do sunscreens increase or decrease melanoma risk: An epidemiologic evaluation.". Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings 4: 97–100. doi:10.1038/sj.jidsp..

- ↑ Vainio, H., Bianchini, F. (2000). "Cancer-preventive effects of sunscreens are uncertain.". Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health 26: 529–31.

- ↑ Ainsleigh HG (1993). "Beneficial effects of sun exposure on cancer mortality.". Prev Med. 22 (1): 132–40. doi:10.1006/pmed.1993.1010. PMID 8475009.

- ↑ Anti Aging Source Skin Cancer Facts (http://www.anti-aging-source.com/skin-cancer-facts.html)

- ↑ Merkel cell carcinoma (http://www.merkelcell.org)

- ↑ Morita A. "Tobacco smoke causes premature skin aging." J Dermatol Sci 2007 48(3):169-75. 3 September 2008.

- ↑ http://skincancer.about.com/gi/dynamic/offsite.htm?zi=1/XJ&sdn=skincancer&cdn=health&tm=19&f=00&su=p726.5.336.ip_&tt=2&bt=0&bts=0&zu=http%3A//www.cancer.org/docroot/NWS/content/NWS_1_1x_Smoking_Linked_to_Skin_Cancer.asp

- ↑ http://www.cancer.org.au/cancersmartlifestyle/SunSmart/Whatputsyouatrisk.htm Cancer Council Australia: What puts you at risk?

- ↑ PMID 20616098 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Cosmos Online - Skin cancer vaccine within reach (http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/news/2327/skin-cancer-vaccine-within-reach)

- ↑ ""Squamous cell carcinoma (epidermoid carcinoma) - skin" pathologyatlas.ro". http://www.pathologyatlas.ro/squamous-cell-carcinoma-skin.php. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Doherty, Gerard M.; Mulholland, Michael W. (2005). Greenfield's Surgery: Scientific Principles And Practice. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5626-X.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Anti-cancer cream fights wrinkles". BBC News. 2009-06-16. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/8101677.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ CBS 2010http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/03/12/health/main6292119.shtml

- ↑ Maurice M Khosh, MD, FACS. "Skin Grafts, Full-Thickness". eMedicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/876379-overview.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Epidemic of Skin Cancer in the U.S.?". http://www.webmd.com/melanoma-skin-cancer/news/20100316/epidemic-of-skin-cancer-in-the-united-states. Retrieved 2010/07/02.

- ↑ "Skin Cancer Facts". http://www.skincancer.org/Skin-Cancer-Facts/. Retrieved 2010/07/02.

- ↑ "Malignant Melanoma Cancer". http://www.skincancerjournal.com/melanoma/. Retrieved 2010/07/02.

- ↑ "Skin Cancer – UK Incidence Statistics". http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/skin/incidence/index.htm. Retrieved 2010/07/02.

- ↑ "UK Children Have Europe's Highest Skin Cancer Rates". http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/106249.php. Retrieved 2010/07/02.

- ↑ "Skin Cancer Facts and Figures". http://www.cancer.org.au/cancersmartlifestyle/SunSmart/Skincancerfactsandfigures.htm. Retrieved 2010/07/02.

External links

- skintumor.info Gallery

- American Cancer Society's Detailed Guide: Skin Cancer - Basal and Squamous Cell

- American Cancer Society's Detailed Guide: Skin Cancer - Melanoma

- skin neoplasm

- Medical Encyclopedia WebMD: Melanoma/Skin Cancer Health Center

- Medical Encyclopedia WebMD: Skin Cancer, Non Melanoma Guide

- Medical Encyclopedia MayoClinic: Skin cancer

- Skin Cancer Melanoma Warning Signs

- Interactive Health Tutorials Medline Plus: Skin cancer Using animated graphics and you can also listen to the tutorial

- Skin cancer at the Open Directory Project

- Skin cancer at the Yahoo! Directory

- Skin Cancer Foundation - Basal Cell Carcinoma

- Skin Cancer Foundation - Melanoma

- Skin Cancer Foundation - Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- Skin Cancer Foundation - Skin Cancer Facts

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||