Cholecystitis

| Cholecystitis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

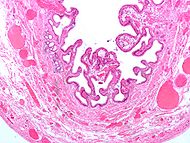

Micrograph of a gallbladder with cholecystitis and cholesterolosis. |

|

| ICD-10 | K81. |

| ICD-9 | 575.0, 575.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 2520 |

| eMedicine | med/346 |

| MeSH | D002764 |

Cholecystitis is inflammation of the gall bladder.

Contents |

Causes and pathology

Cholecystitis is often caused by cholelithiasis (the presence of choleliths, or gallstones, in the gallbladder), with choleliths most commonly blocking the cystic duct directly. This leads to inspissation (thickening) of bile, bile stasis, and secondary infection by gut organisms, predominantly E. coli and Bacteroides species.

The gallbladder's wall becomes inflamed. Extreme cases may result in necrosis and rupture. Inflammation often spreads to its outer covering, thus irritating surrounding structures such as the diaphragm and bowel.

Less commonly, in debilitated and trauma patients, the gallbladder may become inflamed and infected in the absence of cholelithiasis, and is known as acute acalculous cholecystitis.

Stones in the gallbladder may cause obstruction and the accompanying acute attack. The patient might develop a chronic, low-level inflammation which leads to a chronic cholecystitis, where the gallbladder is fibrotic and calcified.

Symptoms

Cholecystitis usually presents as a pain in the right upper quadrant. This is usually a constant, severe pain. The pain may be felt to 'refer' to the right flank or right scapular region at first.

This may also present with the above mentioned pain after eating greasy or fatty foods such as pastries, pies, galoshes and fried foods.

This is usually accompanied by a low grade fever, vomiting and nausea.

More severe symptoms such as high fever, shock and jaundice indicate the development of complications such as abscess formation, perforation or ascending cholangitis. Another complication, gallstone ileus, occurs if the gallbladder perforates and forms a fistula with the nearby small bowel, leading to symptoms of intestinal obstruction.

Chronic cholecystitis manifests with non-specific symptoms such as nausea, vague abdominal pain, belching, and diarrhea.

Diagnosis

Cholecystitis is usually diagnosed by a history of the above symptoms, as well examination findings:

- fever (usually low grade in uncomplicated cases)

- tender right upper quadrant +/- Murphy's sign

Subsequent laboratory and imaging tests are used to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other possible causes.

Ultrasound can assist in the differential.[1][2]

Differential diagnosis

Acute cholecystitis

- This should be suspected whenever there is acute right upper quadrant or epigastric pain.

- Other possible causes include:

- Perforated peptic ulcer

- Acute peptic ulcer exacerbation

- Amoebic liver abscess

- Acute amoebic liver colitis

- Acute pancreatitis

- Acute intestinal obstruction

- Renal colic

- Acute retrocolic appendicitis

- Other possible causes include:

Chronic cholecystitis

- The symptoms of chronic cholecystitis are non-specific, thus chronic cholecystitis may be mistaken for other common disorders:

- Peptic ulcer

- Hiatus hernia

- Colitis

- Functional bowel syndrome

It is defined pathologically by the columnar epithelium has reached down the muscular layer.

Quick Differential

- Biliary colic - Caused by obstruction of the cystic duct. It is associated with sharp and constant epigastric pain in the absence of fever and usually there is a negative Murphy's sign. Liver function tests are within normal limits since the obstruction does not necessarily cause blockage in the common hepatic duct, thereby allowing normal bile excretion from the liver. An ultrasound scan is used to visualise the gallbladder and associated ducts, and also to determine the size and precise position of the obstruction.

- Cholecystitis - Caused by blockage of the cystic duct with surrounding inflammation, usually due to infection. Typically, the pain is initially 'colicky' (intermittent), and becomes constant and severe, mostly in the right upper quadrant. Infectious agents that cause cholecystitis include E coli, klebsiella, pseudomonas, B. fragilis and enterococcus. Murphy's sign is positive, particularly because of increased irritation of the gallbladder lining, and similarly this pain radiates (spreads) to the shoulder, flank or in a band like pattern around the lower abdomen. Laboratory tests frequently show raised hepatocellular liver enzymes (AST, ALT) with a high white cell count (WBC). Ultrasound is used to visualise the gallbladder and ducts.

- Choledocholithiasis - This refers to blockage of the common bile duct where a gallstone has left the gallbladder or has formed in the common bile duct (primary cholelithiasis). As with other biliary tree obstructions it is usually associated with 'colicky' pain, and because there is direct obstruction of biliary output, obstructive jaundice. Liver function tests will therefore show increased serum bilirubin, with high conjugated bilirubin. Liver enzymes will also be raised, predominately GGT and ALP, which are associated with biliary epithelium. The diagnosis is made using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), or the nuclear alternative (MRCP). One of the more serious complications of choledocholithiasis is acute pancreatitis, which may result in significant permanent pancreatic damage and brittle diabetes.

- Cholangitis - An infection of entire biliary tract, and may also be known as 'ascending cholangitis', which refers to the presence of pathogens that typically inhabit more distal regions of the bowel[3]

Cholangitis is a medical emergency as it may be life threatening and patients can rapidly succumb to acute liver failure or bacterial sepsis. The classical sign of cholangitis is Charcot's triad, which is right upper quadrant pain, fever and jaundice. Liver function tests will likely show increases across all enzymes (AST, ALT, ALP, GGT) with raised bilirubin. As with choledocholithiasis, diagnosis is confirmed using cholangiopancreatography.

It is worth noting that bile is an extremely favourable growth medium for bacteria, and infections in this space develop rapidly and may become quite severe.

Investigations

Blood

Laboratory values may be notable for an elevated alkaline phosphatase, possibly an elevated bilirubin (although this may indicate choledocholithiasis), and possibly an elevation of the WBC count. CRP (C-reactive protein) is often elevated. The degree of elevation of these laboratory values may depend on the degree of inflammation of the gallbladder. Patients with acute cholecystitis are much more likely to manifest abnormal laboratory values, while in chronic cholecystitis the laboratory values are frequently normal.

Radiology

Sonography is a sensitive and specific modality for diagnosis of acute cholecystitis; adjusted sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of acute cholecystitis are 88% and 80%, respectively. The 2 major diagnostic criteria are cholelithiasis and sonographic Murphy's sign. Minor criteria include gallbladder wall thickening greater than 3mm, pericholecystic fluid, and gallbladder dilatation.

The reported sensitivity and specificity of CT scan findings are in the range of 90-95%. CT is more sensitive than ultrasonography in the depiction of pericholecystic inflammatory response and in localizing pericholecystic abscesses, pericholecystic gas, and calculi outside the lumen of the gallbladder. CT cannot see noncalcified gallbladder calculi, and cannot assess for a Murphy's sign.

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy with technetium-99m DISIDA (bilirubin) analog is also sensitive and accurate for diagnosis of chronic and acute cholecystitis. It can also assess the ability of the gall bladder to expel bile (gall bladder ejection fraction), and low gall bladder ejection fraction has been linked to chronic cholecystitis. However, since most patients with right upper quadrant pain do not have cholecystitis, primary evaluation is usually accomplished with a modality that can diagnose other causes, as well.

Therapy

For most patients, in most centres, the definitive treatment is surgical removal of the gallbladder. Supportive measures are instituted in the meantime and to prepare the patient for surgery. These measures include fluid resuscitation and antibiotics. Antibiotic regimens usually consist of a broad spectrum antibiotic such as piperacillin-tazobactam (Zosyn), ampicillin-sulbactam (Unasyn), ticarcillin-clavulanate (Timentin), or a cephalosporin (e.g.ceftriaxone) and an antibacterial with good coverage (fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin) and anaerobic bacteria coverage, such as metronidazole. For penicillin allergic patients, aztreonam and clindamycin may be used.

Gallbladder removal, cholecystectomy, can be accomplished via open surgery or a laparoscopic procedure. Laparoscopic procedures can have less morbidity and a shorter recovery stay. Open procedures are usually done if complications have developed or the patient has had prior surgery to the area, making laparoscopic surgery technically difficult. A laparoscopic procedure may also be 'converted' to an open procedure during the operation if the surgeon feels that further attempts at laparoscopic removal might harm the patient. Open procedure may also be done if the surgeon does not know how to perform a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

In cases of severe inflammation, shock, or if the patient has higher risk for general anesthesia (required for cholecystectomy), the managing physician may elect to have an interventional radiologist insert a percutaneous drainage catheter into the gallbladder ('percutaneous cholecystostomy tube') and treat the patient with antibiotics until the acute inflammation resolves. The patient may later warrant cholecystectomy if their condition improves.

Complications of cholecystitis

- Perforation or rupture

- Ascending cholangitis

- Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses

Complications of cholecystectomy

- bile leak ("biloma")

- bile duct injury (about 5-7 out of 1000 operations. Open and laparoscopic surgeries have essentially equal rate of injuries, but the recent trend is towards fewer injuries with laparoscopy. It may be that the open cases often result because the gallbladder is too difficult or risky to remove with laparoscopy)

- abscess

- wound infection

- bleeding (liver surface and cystic artery are most common sites)

- hernia

- organ injury (intestine and liver are at highest risk, especially if the gallbladder has become adherent/scarred to other organs due to inflammation (e.g. transverse colon)

- deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (unusual- risk can be decreased through use of sequential compression devices on legs during surgery)

- fatty acid and fat-soluble vitamin malabsorption

Gall bladder perforation

Gall bladder perforation (GBP) is a rare but life-threatening complication of acute cholecystitis. The early diagnosis and treatment of GBP are crucial to decrease patient morbidity and mortality.

Approaches to this complication will vary based on the condition of an individual patient, the evaluation of the treating surgeon or physician, and the facilities' capability. Perforation can happen at the neck from pressure necrosis due to the impacted calculus, or at the fundus. It can result in a local abscess, or perforation into the general peritoneal cavity. If the bile is infected, diffuse peritonitis may occur readily and rapidly and may result in death.

A retrospective study looked at 332 patients who received medical and/or surgical treatment with the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. Patients were treated with analgesics and antibiotics within the first 36 hours after admission (with a mean of 9 hours), and proceeded to surgery for a cholecystectomy. Two patients died and 6 patients had further complications. The morbidity and mortality rates were 37.5% and 12.5%, respectively in the present study. The authors of this study suggests that early diagnosis and emergency surgical treatment of gallbladder perforation are of crucial importance.[4]

See also

- gallstone

- Boas' sign

- Murphy's sign

References

- ↑ Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, et al. (November 1994). "Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease". Arch. Intern. Med. 154 (22): 2573–81. PMID 7979854. http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7979854.

- ↑ Fink-Bennett D, Freitas JE, Ripley SD, Bree RL (August 1985). "The sensitivity of hepatobiliary imaging and real-time ultrasonography in the detection of acute cholecystitis". Arch Surg 120 (8): 904–6. PMID 3893388. http://archsurg.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=3893388.

- ↑ Sung JY; Costerton JW; Shaffer EA (1992). "Defense system in the biliary tract against bacterial infection". World J. Gastroenterol. 37 (5): 689–96. PMID 1563308.

- ↑ Derici H, Kara C, Bozdag AD, Nazli O, Tansug T, Akca E (2006). "Diagnosis and treatment of gallbladder perforation". World J. Gastroenterol. 12 (48): 7832–6. PMID 17203529.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||