Thalidomide

|

|

|---|---|

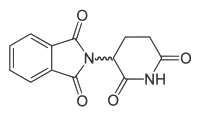

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (RS)-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1H-isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 50-35-1 |

| ATC code | L04AX02 |

| PubChem | CID 5426 |

| DrugBank | DB01041 |

| ChemSpider | 5233 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C13H10N2O4 |

| Mol. mass | 258.23 g/mol |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 55% and 66% for the (+)-R and (–)-S enantiomers, respectively |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2C19)[1] |

| Half-life | mean ranges from approximately 5 to 7 hours following a single dose; not altered with multiple doses |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | X(AU) X(US) |

| Legal status | ℞ Prescription only |

| Routes | oral |

| |

|

Thalidomide (pronounced /θəˈlɪdəmaɪd/) was introduced as a sedative drug in the late 1950s. In 1961, it was withdrawn due to teratogenicity and neuropathy. There is now a growing clinical interest in thalidomide, and it is introduced as an immunomodulatory agent used primarily, combined with dexamethasone, to treat multiple myeloma. The drug is a potent teratogen in zebrafish, chickens,[2] rabbits and primates including humans: severe birth defects may result if the drug is taken during pregnancy.[3]

Thalidomide was sold in a number of countries across the world from 1957 until 1961 when it was withdrawn from the market after being found to be a cause of birth defects in what has been called "one of the biggest medical tragedies of modern times".[4] It is not known exactly how many worldwide victims of the drug there have been, although estimates range from 10,000 to 20,000.[5] Since then thalidomide has been found to be a valuable treatment for a number of medical conditions and it is being prescribed again in a number of countries, although its use remains controversial.[6][7] The thalidomide tragedy led to much stricter testing being required for drugs and pesticides before they can be licensed.[8]

Contents |

History

Development

Thalidomide was developed by German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal in Stolberg (Rhineland) near Aachen, although this claim has recently been challenged. A report published by Martin W. Johnson, director of the Thalidomide Trust in the United Kingdom, mentioned evidence found by Argentinian author Carlos De Napoli that suggested the drug had been developed as an antidote to nerve gases such as Sarin in Germany in 1944, ten years before Grünenthal secured a patent in 1954.[9] De Napoli suggested elsewhere that thalidomide may have been first synthesised by British scientists at the University of Nottingham in 1949.[10] Thalidomide, launched by Grünenthal on 1 October 1957,[11] was found to act as an effective tranquiliser and painkiller and was proclaimed a "wonder drug" for insomnia, coughs, colds and headaches. It was also found to be an effective antiemetic which had an inhibitory effect on morning sickness, and so thousands of pregnant women took the drug to relieve their symptoms.[5] At the time of the drug's development it was not thought likely that any drug could pass from the mother across the placental barrier and harm the developing fetus.[8]

Birth defects

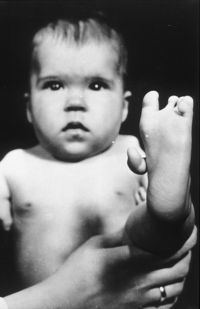

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, more than 10,000 children in 46 countries were born with deformities such as phocomelia, as a consequence of thalidomide use.[12] The Australian obstetrician William McBride and the German pediatrician Widukind Lenz suspected a link between birth defects and the drug, and this was proved by Lenz in 1961.[13][14] McBride was later awarded a number of honours including a medal and prize money by the prestigious L'Institut de la Vie in Paris.[15]

In the United Kingdom the drug was licensed in 1958 and, of the approximately 2000 babies born with defects, 466 survived.[16] The drug was withdrawn in 1961 but it was not until 1968, after a long campaign by The Sunday Times newspaper, that a compensation settlement for the UK victims was reached with Distillers Company Limited.[17][18] In Germany approximately 2,500 thalidomide babies were born.[14]

The impact in the United States was minimized when pharmacologist and M.D. Frances Oldham Kelsey refused Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for an application from Richardson Merrell to market thalidomide, saying further studies were needed. And although thalidomide was never approved for sale in the United States, millions of tablets had been distributed to physicians during a clinical testing program. It was impossible to know how many pregnant women had been given the drug to help alleviate morning sickness or as a sedative.[19]

Canada was the last country to stop the sales of the drug, in early 1962.[20]

In 1962, the United States Congress enacted laws requiring tests for safety during pregnancy before a drug can receive approval for sale in the U.S.[21] Other countries enacted similar legislation, and thalidomide was not prescribed or sold for decades.

Mechanism

It was soon discovered that only one particular optical isomer of thalidomide caused the teratogenicity. The pair of enantiomers, while mirror images of each other, cause different effects[22], although it is now known that the "safe" isomer can be converted to the teratogenic isomer once in the human body.[14][23](see Teratogenic mechanism).

Revived interest

In 1964 Jacob Sheskin, Professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem at Hadassah University Hospital (he was also the chief staff and manager of Hansen Leper Hospital in Jerusalem), administered thalidomide to a critically ill patient with erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), a painful complication of leprosy, in an attempt to relieve his pain in spite of the ban. The patient slept for hours, and was able to get out of bed without aid upon awakening. The result was followed by more favorable experiences and then by a clinical trial.[24] He found that patients with erythema nodosum leprosum, a painful skin condition, experienced relief of their pain by taking thalidomide.

Further work conducted in 1991 by Dr. Gilla Kaplan at Rockefeller University in New York City showed that thalidomide worked in leprosy by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor alpha and believed it would be an effective treatment for AIDS. Kaplan partnered with Celgene Corporation to further develop the potential for thalidomide in AIDS and tuberculosis. However, clinical trials for AIDS proved disappointing.

In 1994, Dr. Robert D'Amato at Harvard Medical School discovered that thalidomide was a potent inhibitor of new blood vessel growth (known as angiogenesis). Numerous cancer clinical trials were initiated with thalidomide based upon this finding and subsequently in 1997 Dr. Bart Barlogie’s reported thalidomide’s initial effectiveness against Multiple Myeloma and it was later approved in the United States by the FDA for use in this malignancy. The FDA has also approved the drug's use in the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum. There are studies underway to determine the drug's effects on arachnoiditis and several types of cancers. However, physicians and patients alike must go through a special process to prescribe and receive thalidomide (S.T.E.P.S.) to ensure no more children are born with birth defects traceable to the medication. Celgene Corporation has also developed analogues to thalidomide, such as lenalidomide, that are substantially more powerful and have fewer side effects — except for greater myelosuppression.[25]

More recently the World Health Organisation (WHO) have stated that:

"The WHO does not recommend the use of thalidomide in leprosy as experience has shown that it is virtually impossible to develop and implement a fool-proof surveillance mechanism to combat misuse of the drug. The drug clofazimine is now a component of the multidrug therapy (MDT), introduced by WHO in 1981 as the standard treatment for leprosy and now supplied free of charge to all patients worldwide."[26]

United States

On July 16, 1998, the FDA approved the use of thalidomide for the treatment of lesions associated with Erythema Nodosum Leprosum (ENL). Because of thalidomide’s potential for causing birth defects, the distribution of the drug was permitted only under tightly controlled conditions. The FDA required that Celgene Corporation, which planned to market thalidomide under the brand name Thalomid, establish a System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (S.T.E.P.S.) oversight program. The conditions required under the program include; limiting prescription and dispensing rights only to authorized prescribers and pharmacies, keeping a registry of all patients prescribed thalidomide, providing extensive patient education about the risks associated with the drug and providing periodic pregnancy tests for women who are prescribed it.[27] On May 26, 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval for thalidomide (Thalomid, Celgene Corporation) in combination with dexamethasone for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients.[28] The FDA approval came seven years after the first reports of efficacy in the medical literature[29] and Celgene took advantage of "off-label" marketing opportunities to promote the drug in advance of its FDA approval for the myeloma indication. Thalomid, as the drug is commercially known, sold over $300 million per year, while only approved for leprosy.[30]

United Kingdom

Thalidomide is available to only a small number of patients in the UK, generally in specialist cancer treatment centres where research trials are taking place and specialist doctors have experience in its use.[31]

Brazil

Brazil has the second highest prevalence rate of leprosy in the world and thalidomide has been used by Brazilian physicians as the drug of choice for the treatment of severe ENL since 1965. A study published in 1994 found 61 people born after 1965 whose limb defects and exposure history were compatible with thalidomide embryopathy. In 63.6% of these cases, thalidomide had been prescribed without the physician informing the patient about the drug's teratogenicity. Since then production, dispensing and prescription of thalidomide have been strictly controlled, but cases of thalidomide embryopathy are thought to have occurred until today.[32][33]

Possible indications

Serious infections including sepsis and tuberculosis cause the level of Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) to rise. TNFα is a chemical mediator in the body, and it may enhance the wasting process in cancer patients as well. Thalidomide may reduce the levels of TNFα, and it is possible that the drug's effect on ENL is caused by this mechanism.[21]

Thalidomide also has potent anti-inflammatory effects that may help ENL patients. In July 1998, the FDA approved the application of Celgene to distribute thalidomide under the brand name Thalomid for treatment of ENL. Pharmion Corporation, who licensed the rights to market Thalidomide in Europe, Australia and various other territories from Celgene, received approval for its use against multiple myeloma in Australia and New Zealand in 2003.[34] Thalomid, in conjunction with dexamethasone, is now standard therapy for multiple myeloma.

Thalidomide is also prescribed for its anti-inflammatory effects in actinic prurigo, an autoimmune skin disease. Thalidomide has been used in chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood (CBDC) with encouraging results.[35] Although, peripheral neuritis may be a limiting factor for long term use of thalidomide.

Thalidomide also inhibits the growth of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), which may be useful in treating macular degeneration and other diseases. This effect helps AIDS patients with Kaposi's sarcoma, although there are better and cheaper drugs to treat the condition. Thalidomide may be able to fight painful, debilitating aphthous lesions in the mouth and esophagus of AIDS patients which prevent them from eating. The FDA formed a Thalidomide Working Group in 1994 to provide consistency between its divisions, with particular emphasis on safety monitoring. The agency also imposed severe restrictions on the distribution of Thalomid through the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS) program.[21]

Thalidomide is also being investigated for treating symptoms of prostate cancer, glioblastoma, lymphoma, arachnoiditis, Behçet's disease, and Crohn's disease. In a small trial, Australian researchers found thalidomide sparked a doubling of the number of T cells in patients, allowing the patients' own immune system to attack cancer cells.

Full list of indications currently being investigated in clinical trials:[36]

|

|

|

Studies carried out in animal models have suggested that the use of combined therapy with thalidomide and glucantime could have a therapeutic benefit in the treatment of *Visceral Leshmaniasis.[37]

A study published in April 2010 discusses the ability of thalidomide to induce vessel maturation, which may be useful as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of vascular malformations. The research was conducted in an experimental model of the genetic disease hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.[38]

Thalidomide and multiple myeloma

Thalidomide was first tested in humans as a single agent for the treatment of multiple myeloma in 1996 due to its antiangiogenic activity and the full study published in 1999.[39] Since then many studies have shown that thalidomide in combination with dexamethasone has increased the survival of multiple myeloma patients. The combination of thalidomide and dexamethasone, often in combination with melphalan, is now one of the most common regimens for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, with an improved response rate of up to 60-70%.[40][41] However, thalidomide may also cause side effects such as polyneuropathy, fatigue, skin rash, and venous thromboembolism (VTE), or blood clots, which could lead to stroke or myocardial infarction.[42] Bennett et al. have conducted a systematic review of VTE associated with thalidomide in multiple myeloma patients.[43] They have found that when Thalidomide was administered without prophylaxis, VTE rates reached as high as 26%. Owing to the high rates of VTE associated with thalidomide in combination with dexamethasone or doxorubicin, a black box warning was added in the US in 2006 to the package insert for thalidomide, indicating that patients with multiple myeloma who receive thalidomide-dexamethasone may benefit from concurrent thromboembolism prophylaxis or aspirin. In addition, owing to these side effects, newer drugs, such as a thalidomide derivative lenalidomide (marketed as Revlimid) and bortezomib (marketed as Velcade) have increased in popularity.

Teratogenic mechanism

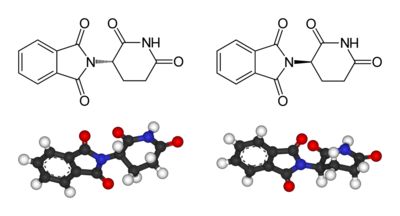

Left: (S)-thalidomide

Right: (R)-thalidomide

Thalidomide is racemic – it contains both left- and right-handed isomers in equal amounts. The (R) enantiomer is effective against morning sickness but the (S) is teratogenic. The enantiomers can interconvert in vivo[44] – that is, if a human is given pure (R)-thalidomide or (S)-thalidomide, both isomers will later be found in the serum – therefore, administering only one enantiomer will not prevent the teratogenic effect.

The mechanism of thalidomide's teratogenic action has led to over 2000 research papers and the proposal of fifteen or sixteen plausible mechanisms.[45] A theoretical synthesis in 2000[45] suggested the following mechanism: Thalidomide intercalates (inserts itself) into DNA in G-C (guanine-cytosine) rich regions.[46][47] Owing to its glutarimide part, (S) thalidomide fits neatly into the major groove of DNA at purine sites.[45] Such intercalation impacts upon the promoter regions of the genes controlling the development of limbs, ears, and eyes such as IGF-I and FGF-2. These normally activate the production of the cell surface attachment integrin αvβ3 with the resulting alphavbeta3 integrin dimer stimulating angiogenesis in developing limb buds. This then promotes the outgrowth of the bud (IGF-I and FGF-2 are also both known to stimulate angiogenesis). Therefore, by inhibiting the chain of events, thalidomide causes the truncation of limb development. In 2009 this theory[45] received strong support, with research showing "conclusively that loss of newly formed blood vessels is the primary cause of thalidomide teratogenesis, and developing limbs are particularly susceptible because of their relatively immature, highly angiogenic vessel network."[48]

Inactivation of the protein cereblon

Thalidomide binds to and inactivates the protein cereblon, which is important in limb formation.[49] The inactivation, thus, leads to a teratogenic effect on fetal development. This was confirmed when the scientists, using genetic techniques, reduced the production of cereblon in developing chick embryo and zebrafish embryo. These embryos had defects similar to those treated with thalidomide. Thus the mechanism that causes teratogenicity has been established but the mechanism for other therapeutic effects remains unclear.[50]

Other side effects

Apart from its infamous tendency to induce birth defects and peripheral neuropathy, the main side effects of thalidomide include fatigue and constipation. It is also associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis especially when combined with dexamethasone, as it is for treatment of multiple myeloma. High doses can lead to pulmonary oedema, atelectasis, aspiration pneumonia and refractory hypotension. In multiple myeloma patients, concomitant use with zoledronic acid may lead to increased incidence of renal dysfunction.

Thalidomide analogs

The exploration of the antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory activities of thalidomide has led to the study and creation of thalidomide analogs. In 2005, Celgene received FDA approval for lenalidomide (Revlimid) as the first commercially useful derivative. Revlimid is only available in a restricted distribution setting to avoid its use during pregnancy. Further studies are being conducted to find safer compounds with useful qualities. Another analog, Actimid (CC-4047), is in the clinical trial phase.[51] These thalidomide analogs can be used to treat different diseases, or used in a regimen to fight two conditions.[52]

Notable people affected

- Louise Medus Mansell, daughter of David Mason, campaigner for increased compensation for thalidomide children, born with no arms or legs.[53]

- Thomas Quasthoff is an internationally acclaimed bass-baritone who describes himself: "1.34 meters tall, short arms, seven fingers — four right, three left — large, relatively well formed head, brown eyes, distinctive lips; profession: singer."[54]

- David Lega, Swedish swimmer, paralympian and current holder of 5 world records.[55]

- Mat Fraser, musician, actor and performance artist born with phocomelia of both arms.

- Terry Wiles, born with phocomelia of both arms and legs and has become known internationally through the television drama On Giant's Shoulders and the best-selling book of the same name.

- Niko von Glasow produced a documentary based on the lives of 12 people affected by the drug, which was released in 2008 entitled Nobody's perfect.[56][57]

- Tony Melendez, award winning singer and guitarist who has become known internationally due to the recognition received from Pope John Paul II and U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

References

- ↑ Ando Y, Fuse E, Figg WD (June 1, 2002). "Thalidomide metabolism by the CYP2C subfamily". Clinical Cancer Research : an Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 8 (6): 1964–73. PMID 12060642. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12060642. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Ito, T., Ando, H., Suzuki, T., Ogura, T., Hotta, K., Imamura, Y., Yamaguchi, Y. and Handa, H. (2010). Identification of a Primary Target of Thalidomide Teratogenicity. Science 327, 1345-1350.

- ↑ Thalidomide: Drug safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding / DRUGSAFETYSITE.COM

- ↑ Anon. "Thalidomide - A Second Chance? - programme summary". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2004/thalidomide.shtml. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Anon. "Born Freak". Happy Birthday Thalidomide. Channel 4. http://www.channel4.com/life/microsites/B/bornfreak/birthday.html. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Anon (March 10, 2006). "Thalidomide:controversial treatment for multiple myeloma". Health news. http://www.healthyforms.com/health-news/2006/03/thalidomide-controversial-treatment.php. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Bowditch, Gillian (March 26, 2006). "Can thalidomide ever be trusted?". The Sunday Times (London: News International Limited). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/scotland/article695193.ece?token=null&offset=0&page=1. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Heaton, C. A. (1994). The Chemical Industry. Springer. pp. 40. ISBN 0751400181.

- ↑ Foggo, Daniel (2009-02-08). "Thalidomide 'was created by the Nazis'". London: The Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article5683577.ece. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Foggo, Daniel (13 September 2009). "Thalidomide victim Gary Syner to go on hunger strike". The Sunday Times (London: Times Newspapers Ltd.). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article6832320.ece. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

- ↑ Moghe, Vijay V; Ujjwala Kulkarni, Urvashi I Parmar (2008). "Thalidomide" (PDF). Bombay Hospital Journal (Bombay: Bombay Hospital) 50 (3): 446. http://www.bhj.org/journal/2008_5003_july/download/page-472-476.pdf. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ Bren, Linda (2001-02-28). "Frances Oldham Kelsey: FDA Medical Reviewer Leaves Her Mark on History". FDA Consumer (US Food and Drug Administration). http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps1609/www.fda.gov/fdac/features/2001/201_kelsey.html. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ Anon. "Widukind Lenz". who name it?. Ole Daniel Enersen. http://www.whonamedit.com/doctor.cfm/1002.html. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Anon (2002-06-07). "Thalidomide:40 years on". BBC news (BBC). http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/2031459.stm. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Report of Thalidomide at University of New South Wales. See also main William McBride article.

- ↑ "Apology for thalidomide survivors". BBC News:Health (BBC News). 14 January 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/8458855.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ↑ Ryan, Caroline (1 April 2004). "They just didn't know what it would do". BBC News:Health (BBC news). http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/3589173.stm. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Flintoff, John-Paul (March 23, 2008). "Thalidomide: the battle for compensation goes on". The Sunday Times (London: Times Newspapers Ltd.). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article3602694.ece. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Mekdeci, Betty. "How a Commonly Used Drug Caused Birth Defects". http://www.birthdefects.org/research/bendectin_1.php.

- ↑ "Turning Points of History - Prescription for Disaster". History Television. http://www.history.ca/ontv/titledetails.aspx?titleid=21267. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Burkholz, Herbert (1997-09-01). "Giving Thalidomide a Second Chance". FDA Consumer (US Food and Drug Administration). http://www.fda.gov/fdac/features/1997/697_thal.html. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- ↑ Eccles H; Ratcliff B (2001). Chemistry 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 170. ISBN 978-0-521-79882-2.

- ↑ Ligham, Alex (April 2000). "Optical Isomerism In Thalidomide". Thalidomide. http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/motm/thalidomide/optical2iso.html. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ↑ Silverman, MD, William (2002-04-22). "The Schizophrenic Career of a "Monster Drug"". Pediatrics 110 (2): 404–406. doi:10.1542/peds.110.2.404. PMID 12165600. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/110/2/404. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- ↑ Rao KV (September 2007). "Lenalidomide in the treatment of multiple myeloma". American Journal of Health-system Pharmacy : AJHP : Official Journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists 64 (17): 1799–807. doi:10.2146/ajhp070029. PMID 17724360.

- ↑ Anon. "Use of thalidomide in leprosy". WHO:leprosy elimination. WHO. http://www.who.int/lep/research/thalidomide/en/index.html. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, July 16, 1998

- ↑ FDA Approves Thalomid (thalidomide) to Treat Multiple Myeloma

- ↑ Desikan, R; N. Munsi, J. Zeldis et al. (1999). "Activity of thalidomide (THAL) in multiple myeloma (MM) confirmed in 180 patients with advanced disease". Blood 94 (Suppl. 1): 603a-603a.

- ↑ Ismail, MA (2005-07-07). "FDA: A Shell of its Former Self". Pushing Prescriptions. The Centre for Public Integrity. http://projects.publicintegrity.org/rx//report.aspx?aid=722.

- ↑ Anon. "Thalidomide". Cancer treatments. Cancerbackup. http://www.cancerbackup.org.uk/Treatments/Biologicaltherapies/Angiogenesisinhibitors/Thalidomide. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Paumgartten, FJ; Chahoud, I; Chahoud, Ibrahim (July 2006). "Thalidomide embryopathy cases in Brazil after 1965". Reproductive Toxicology (Elselvier) 22 (1): 1,2. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.11.007. PMID 16427249. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TC0-4J2W0DX-1&_user=899537&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000047642&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=899537&md5=064ddf875924b5b116f6ed8d82049b07.

- ↑ Correio Braziliense (January 2006). Talidomida volta a assustar. http://www.saude.df.gov.br/003/00301009.asp?ttCD_CHAVE=31041.

- ↑ Rouhi, Maureen. "Thalidomide". Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. http://pubs.acs.org/cen/coverstory/83/8325/8325thalidomide.html. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- ↑ http://www.ijdvl.com/text.asp?2010/76/4/427/66601

- ↑ . ADIS R&D Insight. http://bi.adisinsight.com/rdi/viewdocument.aspx?render=view&mode=remote&adnm=800004827&PushValidation=121745. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ Ghassem, Solgi; KARIMINIA A., ABDI K, DARABI M, GHAREGHOZLOO B. (March 2006). "Effects of combined therapy with thalidomide and glucantime on leishmaniasis induced by Leishmania major in BALB/c mice" (PDF). Korean Journal of Parasitology 44 (1): 55–61. doi:10.3347/kjp.2006.44.1.55. PMID 16514283. PMC 2532651. http://synapse.koreamed.org/Synapse/Data/PDFData/0066KJP/kjp-44-55.pdf.

- ↑ Lebrin, Franck; Srun S., Raymond2] K, Martin S., van den Brink S, Freitas C., Bréant C., Mathivet T., Larrivée B., Thomas J., Arthur H., Westermann C., Disch F., Mager J., Snijder R., Eichmann A., Mummery C. (April 2010). "Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia". Nature Medicine 16 (4): 420–428. doi:10.1038/nm.2131. PMID 20364125. http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v16/n4/full/nm.2131.html.

- ↑ Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, et al. (November 1999). "Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma". The New England Journal of Medicine 341 (21): 1565–71. doi:10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. PMID 10564685. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=10564685&promo=ONFLNS19. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Gieseler F (June 2008). "Pathophysiological considerations to thrombophilia in the treatment of multiple myeloma with thalidomide and derivates". Thrombosis and Haemostasis 99 (6): 1001–7. doi:10.1160/TH08-01-0009. PMID 18521500.

- ↑ Denz U, Haas PS, Wäsch R, Einsele H, Engelhardt M (July 2006). "State of the art therapy in multiple myeloma and future perspectives". European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 42 (11): 1591–600. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.040. PMID 16815703.

- ↑ Haas PS, Denz U, Ihorst G, Engelhardt M (April 2008). "Thalidomide in consecutive multiple myeloma patients: single-center analysis on practical aspects, efficacy, side effects and prognostic factors with lower thalidomide doses". Eur. J. Haematol. 80 (4): 303–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.01022.x. PMID 18182082.

- ↑ Bennett CL, Angelotta C, Yarnold PR, et al. (December 2006). "Thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thromboembolism among patients with cancer". JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association 296 (21): 2558–60. doi:10.1001/jama.296.21.2558-c. PMID 17148721.

- ↑ Teo SK, Colburn WA, Tracewell WG, Kook KA, Stirling DI, Jaworsky MS, Scheffler MA, Thomas SD, Laskin OL (2004). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of thalidomide". Clin Pharmacokinet. 43 (5): 311–327. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443050-00004. PMID 15080764.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Stephens TD, Bunde CJ, Fillmore BJ (June 2000). "Mechanism of action in thalidomide teratogenesis". Biochemical Pharmacology 59 (12): 1489–99. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00388-3. PMID 10799645.

- ↑ Koch HP, Czejka MJ. (1986). Evidence for the intercalation of thalidomide into DNA: clue to the molecular mechanism of thalidomide teratogenicity? Z Naturforsch [C]. 41(11-12):1057-61. PMID 2953123

- ↑ Huang PH, McBride WG (1997). "Interaction of [glutarimide-2-14C]-thalidomide with rat embryonic DNA in vivo". Teratogenesis, Carcinogenesis, and Mutagenesis 17 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6866(1997)17:1<1::AID-TCM2>3.0.CO;2-L. PMID 9249925.

- ↑ Therapontos C, Erskine L, Gardner ER, Figg WD, Vargesson N (May 2009). "Thalidomide induces limb defects by preventing angiogenic outgrowth during early limb formation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (21): 8573–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901505106. PMID 19433787.

- ↑ Carl Zimmer (March 15, 2010). "Answers Begin to Emerge on How Thalidomide Caused Defects". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/16/science/16limb.html?ref=science&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2010-03-21. "As they report in the current issue of Science, a protein known as cereblon latched on tightly to the thalidomide."

- ↑ Ito T, Ando H, Suzuki T, Ogura T, Hotta K, Imamura Y, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H (2010). "Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity". Science 327 (5971): 1345–1350. doi:10.1126/science.1177319. PMID 9249925. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/327/5971/1345. Lay summary – BBC News.

- ↑ Search of: pomalidomide - ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Raghupathy R., Billett H.H. ' Promising therapies in sickle cell disease Cardiovascular and Hematological Disorders - Drug Targets 2009 9:1 (1-8)

- ↑ Courtenay-Smith, Natasha (2008-04-23). "A truly special love story: Two married thalidomide survivors living happily 50 years after drug's launch". London: The Daily Mail. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-561360/A-truly-special-love-story-Two-married-thalidomide-survivors-living-happily-50-years-drugs-launch.html. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Orpheus lives: A small good thing in Quastoff Retrieved on 2008-10-22

- ↑ David Lega personal website

- ↑ Nobody's Perfect Release Dates

- ↑ Movie Review of Nobody's Perfect

Further reading

- Stephens, Trent; Brynner, Rock (2001-12-24). Dark Remedy: The Impact of Thalidomide and Its Revival as a Vital Medicine. Perseus. ISBN 0-7382-0590-7.

- Knightley, Phillip; Evans, Harold. Potter, Elaine. Wallace, Marjorie. (1979). Suffer The Children: The Story of Thalidomide. New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-68114-8.

External links

- Thalidomide monograph from Chemical and Engineering News. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5nWHyOCfI)

- Thalidomide product monograph (Needs registration)

- Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation article on Thalidomide

- International Myeloma Foundation article on Thalidomide

- Thalidomide — Annotated List of Links (covering English and German pages)

- WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter No. 2, 2003 - See page 11, Feature Article

- Grünenthal GmbH - Thalidomide

- Celgene website on Thalomid

- The Return of Thalidomide - BBC

- CBC Digital Archives – Thalidomide: Bitter Pills, Broken Promises

- Thalidomide UK

- The Thalidomide Trust

- The International Contergan Thalidomide Alliance website

- "The Big Pitch: How would you conduct a campaign for the new Thalidomide Drugs?", forum of pharmaceutical and medical marketing professionals commenting on how they would address the Thalidomine controversies.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||