Citalopram

Citalopram (trade name: Celexa, Cipramil) is an antidepressant drug of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It has FDA approval to treat major depression, and is prescribed off-label for a number of anxiety conditions.

History

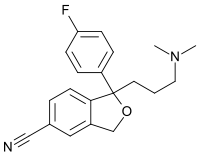

Citalopram (pronounced /saɪˈtælɵpræm/)[1] was originally created in 1989[2] by the pharmaceutical company Lundbeck. The patent expired in 2003, allowing other companies to legally produce generic versions. Lundbeck has recently released an updated formulation called escitalopram (also known as Cipralex or Lexapro), which is the S-enantiomer of the racemic citalopram (see b), and acquired a new patent for it. In the United States, Forest Labs manufactures and markets the drug.

Indications

Approved

Citalopram is approved to treat the symptoms of major depression.[3]

Citalopram HBr tablets in 20 mg (coral, marked 508) and 40 mg (white, marked 509), and a US Penny.

Unapproved, off-label and investigational

Citalopram is frequently used off-label to treat anxiety, panic disorder, ADHD, PMDD, Body dysmorphic disorder and OCD.[4]

Citalopram has been found to greatly reduce the symptoms of diabetic neuropathy[5] and premature ejaculation.[6] There is also evidence that citalopram may be effective in the treatment of post-stroke pathological crying.[7]

While on its own citalopram is less effective than amitriptyline in the prevention of migraines, in refractory cases combination therapy may be more effective.[8]

Citalopram and other SSRIs can be used to treat hot flushes.[9]

A 2009 multisite randomized controlled study found no benefit and some adverse effects in autistic children from citalopram, raising doubts whether SSRIs are effective for treating repetitive behavior in children with autism.[10]

Some research suggests that citalopram interacts with cannabinoid protein-couplings in the rat brain, and this is put forward as a potential cause of some of the drug's antidepressant effect.[11]

Availability

Citalopram is sold under the brand-names Celexa (U.S. and Canada, Forest Laboratories, Inc.), Cipramil (Australia, Brazil, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, United Kingdom, New Zealand, South Africa), Elopram (Italy)[12] Citol, Vodelax (Turkey), Citrol, Seropram, Talam (Europe and Australia), Citabax, Citaxin (Poland), Citalec (Slovakia, Czech Republic), Recital (Israel, Thrima Inc. for Unipharm Ltd.), Zetalo (India), Celapram, Ciazil (Australia, New Zealand), Zentius, Cimal (South America, by Roemmers and Recalcine), Ciprapine (Ireland), Cilift (South Africa), Citox (Mexico), Temperax (Chile, Peru, Argentina), Talohexal (Australia), Citopam (Australia), Akarin (Denmark, Nycomed), Cipram (Turkey, Denmark, H. Lundbeck A/S), Dalsan (Eastern Europe), Pramcit (Pakistan), and Celius (Greece), Humorup (Argentina), Oropram (Iceland, Actavis).

Dosage and administration

Citalopram is available in 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg tablets, as well as 10 mg/5 mL peppermint flavor oral solution. The recommended starting dose is 20 mg/day, with a target dose of 40 mg/day. Increased efficacy has not been proven beyond 40 mg/day, but some prescribers may increase the dose to 60 mg/day or more. The recommendation is that dose increases do not exceed 20 mg/day increases per week.

Citalopram is generally considered safe and well-tolerated in the therapeutic dose range of 10 to 60 mg/day (a dose of 60 mg/day is reserved for patients who do not respond to lower doses). A doctor must always monitor a patient taking an SSRI such as citalopram. Distinct from some other agents in its class, citalopram exhibits linear pharmacokinetics and minimal drug interaction potential, making it a better choice for the elderly or comorbid patients.[13]

Side effects and drug interactions

Citalopram theoretically causes side effects by increasing the concentration of serotonin in other parts of the body (e.g., the intestines). Other side effects, such as increased apathy and emotional flattening, may be caused by the decrease in dopamine release that is associated with increased serotonin. Citalopram is also a mild antihistamine, which may be responsible for some of its sedating properties.[14]

Common side effects of citalopram include drowsiness, insomnia, nausea, weight changes, frequent urination, decreased sex drive, anorgasmia, dry mouth,[15] increased sweating, trembling, diarrhea, excessive yawning, and fatigue. Less common side effects include bruxism, vomiting, cardiac arrhythmia, blood pressure changes, anxiety, mood swings, headache, and dizziness. Rare side effects include convulsions, hallucinations, and severe allergic reactions[16]. If sedation occurs, the dose may be taken at bedtime rather than in the morning.

Citalopram and other SSRIs can induce a mixed state, especially in those with undiagnosed bipolar disorder.[17]

Citalopram should not be taken with St John's wort, as the resulting drug interaction could lead to serotonin syndrome.[18] This may be caused by compounds in the plant extract reducing the efficacy of the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes that process citalopram.[19] It has also been suggested that such compounds, including hypericin, hyperforin and flavonoids, could have SSRI-mimetic effects on the nervous system, although this is still subject to debate.[20] One study found that Hypericum extracts had similar effects in treating moderate depression as citalopram, with fewer side effects.[21]

Citalopram is contraindicated in individuals taking MAOIs, due to potential for serotonin syndrome.

SSRIs, including citalopram, can increase the risk of bleeding, especially when coupled with aspirin, NSAIDs, warfarin, or other anticoagulants.[22]

When taken with Prilosec, the clearance of citalopram may be reduced, leading to higher blood levels of citalopram. Prilosec inhibits the CYP450 2C19 enzyme, one of the two primary enzymes responsible for the metabolism of citalopram. Dosage adjustments may be needed due to this effect.

SSRI discontinuation syndrome has been reported when treatment is stopped. Tapering off citalopram therapy, as opposed to abrupt discontinuation, is recommended in order to diminish the occurrence and severity of discontinuation symptoms. Some doctors may choose to switch a patient to Prozac (Fluoxetine) when discontinuing Citalopram as Prozac has a much longer half-life (i.e. stays in the body longer compared to Citalopram). This may avoid many of the severe withdrawal symptoms associated with Citalopram discontinuation. This can be done either by administering a single 20 mg dose of Prozac or by beginning on a low dosage of Prozac and slowly tapering down. Either of these prescriptions may be written in liquid form to allow a very slow and gradual tapering down in dosage. Alternatively, a patient wishing to stop taking Citalopram may visit a compounding pharmacy where his or her prescription may be re-arranged into progressively smaller dosages.

Suicidality

Citalopram, like other antidepressants, carries a black box warning stating that it may increase suicidal thinking and behavior in those under age 24. Beyond age 24 there is no increased risk for suicidality.[23]

Overdosage

Acute overdosage, usually intentional, has been observed in a number of instances but the outcome is generally favorable. Overdosage may result in vomiting, sedation, disturbances in heart rhythm, dizziness, sweating, nausea, tremor, and rarely amnesia, confusion, coma, or convulsions.[24] A number of overdose deaths have occurred, sometimes involving other drugs but also with citalopram as the sole agent. Citalopram and N-desmethylcitalopram may be quantitated in blood or plasma to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma citalopram concentrations are usually in a range of 50-400 μg/L in persons receiving the drug therapeutically, 1000-3000 μg/L in patients who survive acute overdosage and 3–30 mg/L in those who do not survive.[25][26][27]

Stereochemistry

Citalopram has one stereocenter, to which a 4-fluorophenyl group and an N,N-dimethyl-3-aminopropyl group bind. Due to this chirality, the molecule exists in (two) enantiomeric forms (mirror images). They are termed S-(+)-citalopram and R-(–)-citalopram.

-citalopram-3D-sticks.png) |

-citalopram-3D-sticks.png) |

-citalopram.png) |

-citalopram.png) |

| (S)-(+)-citalopram |

(R)-(–)-citalopram |

Citalopram is sold as a racemic mixture, consisting of 50% (R)-(−)-citalopram and 50% (S)-(+)-citalopram. Only the (S)-(+) enantiomer has the desired antidepressant effect. Lundbeck now markets the (S)-(+) enantiomer, the generic name of which is escitalopram. Whereas citalopram is supplied as the hydrobromide, escitalopram is sold as the oxalate salt (hydrooxalate).[28] In both cases, the salt forms of the amine makes these otherwise lipophilic compounds water-soluble.

Metabolites

Citalopram metabolites desmethylcitalopram and didesmethylcitalopram are significantly less active, and their contribution to the overall action of citalopram is negligible.

Genetic factors related to antidepressant efficacy

Citalopram is a P-glycoprotein (Pgp) substrate and is actively transported by that protein from the brain. The efficacy of citalopram in people possessing a certain version of Pgp (genetic TT-allele) is likely to be diminished. This suggests that in non-responders to citalopram a switch to an antidepressant which is not a Pgp substrate, such as fluoxetine (Prozac, Fontex) or mirtazapine (Remeron)—but not to venlafaxine (Effexor), amitriptyline (Elavil) or paroxetine (Paxil), which are Pgp substrates—may be beneficial.[29]

References

- ↑ "citalopram". Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. http://medical.merriam-webster.com/medical/citalopram. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ↑ Dorell K, Cohen MA, Huprikar SS, Gorman JM, Jones M (2005). "Citalopram-induced diplopia". Psychosomatics 46 (1): 91–3. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.1.91. PMID 15765832.

- ↑ Cerner Multum Inc. Rxlist.com. 2009. http://www.rxlist.com/celexa-drug.htm

- ↑ Poore, Jerod. Celexa. Crazy Meds. 2010. http://crazymeds.us/celexa.html

- ↑ Sindrup SH, Bjerre U, Dejgaard A, Brøsen K, Aaes-Jørgensen T, Gram LF (1992). "The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram relieves the symptoms of diabetic neuropathy". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 52 (5): 547–52. PMID 1424428.

- ↑ Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Semercioz A (2002). "The efficacy of citalopram in the treatment of premature ejaculation (prem-e): a placebo-controlled study". Int. J. Impot. Res. 14 (6): 502–5. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900918. PMID 12494286.

- ↑ Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Riis JO (1993). "Citalopram for post-stroke pathological crying". Lancet 342 (8875): 837–9. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)92696-Q. PMID 8104273.

- ↑ Rampello L, Alvano A, Chiechio S, et al. (2004). "Evaluation of the prophylactic efficacy of amitriptyline and citalopram, alone or in combination, in patients with comorbidity of depression, migraine, and tension-type headache". Neuropsychobiology 50 (4): 322–8. doi:10.1159/000080960. PMID 15539864.

- ↑ Stahl, S. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY. 2009. pp. 87.

- ↑ King BH, Hollander E, Sikich L et al. (2009). "Lack of efficacy of citalopram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behavior: citalopram ineffective in children with autism". Arch Gen Psychiatry 66 (6): 583–90. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.30. PMID 19487623. Lay summary – Los Angeles Times (2009-06-02).

- ↑ Effects of chronic treatment with citalopram on cannabinoid and opioid receptor-mediated G-protein coupling in discrete rat brain regions. Shirley A. Hesketh, Adrian K. Brennan, David S. Jessop and David P. Finn. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. Volume 198, Number 1 / May, 2008. ISSN: 0033-3158 (Print) 1432-2072 (Online) http://www.springerlink.com/content/2127100x043n3674/

- ↑ http://www.drugs.com/international/elopram.html

- ↑ Keller MB (2000). "Citalopram therapy for depression: a review of 10 years of European experience and data from U.S. clinical trials". The Journal of clinical psychiatry 61 (12): 896–908. PMID 11206593. http://www.biopsychiatry.com/citalopram.html.

- ↑ Stahl, S. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY. 2009. pp. 84.

- ↑ Cerner Multum Inc. Drugs.com. 2009. http://www.drugs.com/celexa.html

- ↑ Cerner Multum Inc. Rxlist.com. 2009. http://www.rxlist.com/celexa-drug.htm

- ↑ Stahl, S. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY. 2009. pp. 85.

- ↑ Karch, Amy (2006). 2006 Lippincott's Nursing Drug Guide. Philadephia, Baltimore, New York, London, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 1-58255-436-6.

- ↑ http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/Profs/PUarticles/sjw.htm accessed Feb 27 2009

- ↑ http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/st-johns-000276.htm accessed Feb 27 2009

- ↑ M. Gastpar, et al. (2006). "Comparative Efficacy and Safety of a Once-Daily Dosage of Hypericum Extract STW3-VI and Citalopram in Patients with Moderate Depression: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Multicentre, Placebo-Controlled Study". Pharmacopsychiatry 39 (2): 66–75. doi:10.1055/s-2006-931544. PMID 16555167. http://www.thieme-connect.com/ejournals/abstract/pharmaco/doi/10.1055/s-2006-931544. Retrieved Feb 27 2009.

- ↑ Citalopram PI Sheet. 2009. http://www.frx.com/pi/Citalopram_pi.pdf

- ↑ Citalopraim PI Sheet. 2009. http://www.frx.com/pi/Citalopram_pi.pdf

- ↑ Stahl, S. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY. 2009. pp. 85.

- ↑ Personne M, Sjöberg G, Persson H. Citalopram overdose--review of cases treated in Swedish hospitals. J. Tox. Clin. Tox. 35: 237-240, 1997.

- ↑ Luchini D, Morabito G, Centini F. Case report of a fatal intoxication by citalopram. Am. J. For. Med. Pathol. 26: 352-354, 2005.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 319-322.

- ↑ Celexa.com

- ↑ Uhr M, Tontsch A, Namendorf C, Ripke S, Lucae S, Ising M, Dose T, Ebinger M, Rosenhagen M, Kohli M, Kloiber S, Salyakina D, Bettecken T, Specht M, Pütz B, Binder EB, Müller-Myhsok B, Holsboer F (2008). "Polymorphisms in the Drug Transporter Gene ABCB1 Predict Antidepressant Treatment Response in Depression". Neuron 57 (2): 203–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.017. PMID 18215618.

External links

|

Antidepressants (N06A) |

|

|

Specific reuptake inhibitors (RIs), enhancers (REs), and releasing agents (RAs) |

|

|

|

Alaproclate · Citalopram · Escitalopram · Femoxetine · Fluoxetine · Fluvoxamine · Indalpine · Ifoxetine · Litoxetine · Lubazodone · Panuramine · Paroxetine · Pirandamine · Seproxetine · Sertraline · Vilazodone · Zimelidine |

|

|

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

|

|

|

|

Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (SNDRIs)

|

Brasofensine · BTS-74,398 · Cocaine · Diclofensine · DOV-21,947 · DOV-102,677 · DOV-216,303 · EXP-561 · Fezolamine · JNJ-7,925,476 · NS-2359 · PRC200-SS · Pridefrine · SEP-225,289 · SEP-227,162 · Tesofensine |

|

|

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs)

|

Amedalin · Atomoxetine/Tomoxetine · Binedaline · Ciclazindol · Daledalin · Esreboxetine · Lortalamine · Mazindol · Nisoxetine · Reboxetine · Talopram · Talsupram · Tandamine · Viloxazine |

|

|

Dopamine reuptake inhibitors (DRIs)

|

Medifoxamine · Vanoxerine

|

|

|

Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs)

|

|

|

|

Norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agents (NDRAs)

|

|

|

|

Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agents (SNDRAs)

|

4-Methyl-αMT · αET/Etryptamine · αMT/Metryptamine

|

|

|

Selective serotonin reuptake enhancers (SSREs)

|

Tianeptine

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

|

|

Receptor antagonists and/or reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

Serotonin antagonists and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs)

|

|

|

|

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs)

|

Aptazapine · Esmirtazapine · Mianserin · Mirtazapine · Setiptiline/Teciptiline |

|

|

Norepinephrine-dopamine disinhibitors (NDDIs)

|

Agomelatine

|

|

|

Serotonin modulators and stimulators (SMSs)

|

Lu AA21004

|

|

|

|

|

Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants (TCAs/TeCAs) |

|

Tricyclics: Amezepine · Amineptine · Amitriptyline · Amitriptylinoxide · Azepindole · Butriptyline · Cianopramine · Clomipramine · Cotriptyline · Cyanodothiepin · Demexiptiline · Depramine/Balipramine · Desipramine · Dibenzepine · Dimetacrine · Dosulepin/Dothiepin · Doxepin · Enprazepine · Fluotracen · Hepzidine · Homopipramol · Imipramine · Imipraminoxide · Intriptyline · Iprindole · Ketipramine · Litracen · Lofepramine · Losindole · Mariptiline · Melitracen · Metapramine · Mezepine · Naranol · Nitroxazepine · Nortriptyline · Noxiptiline · Octriptyline · Opipramol · Pipofezine · Propizepine · Protriptyline · Quinupramine · Tampramine · Tianeptine · Tienopramine · Trimipramine; Tetracyclics: 7-OH-Amoxapine · Amoxapine · Aptazapine · Azipramine · Ciclazindol · Ciclopramine · Esmirtazapine · Loxapine · Maprotiline · Mazindol · Mianserin · Mirtazapine · Oxaprotiline · Setiptiline/Teciptiline

|

|

|

|

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) |

|

Nonselective: Irreversible: Benmoxin · Echinopsidine · Iproclozide · Iproniazid · Isocarboxazid · Mebanazine · Metfendrazine · Nialamide · Octamoxin · Phenelzine · Pheniprazine · Phenoxypropazine · Pivalylbenzhydrazine · Safrazine · Tranylcypromine; Reversible: Caroxazone · Paraxazone; MAOA-Selective: Irreversible: Clorgyline; Reversible: Amiflamine · Bazinaprine · Befloxatone · Befol · Brofaromine · Cimoxatone · Esuperone · Harmala Alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) · Methylene Blue · Metralindole · Minaprine · Moclobemide · Pirlindole · Sercloremine · Tetrindole · Toloxatone · Tyrima; MAOB-Selective: Irreversible: Ladostigil · Mofegiline · Pargyline · Rasagiline · Selegiline; Reversible: Lazabemide · Milacemide

|

|

|

|

Azapirones and other 5-HT1A receptor agonists |

|

Alnespirone · Aripiprazole · Befiradol · Buspirone · Eptapirone · Flesinoxan · Flibanserin · Gepirone · Ipsapirone · Oxaflozane · Tandospirone · Vilazodone · Zalospirone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Research compounds and miscellaneous agents |

|

|

5-HT4R agonists

|

RS-67,333 · SL65.0155

|

|

|

5-HT7R antagonists

|

Amisulpride

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

β3-Adrenoceptor agonists

|

Amibegron · Solabegron

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COMT inhibitors

|

Entacapone · Tolcapone

|

|

|

CRF1R antagonists

|

Antalarmin · CP-154,526 · Pexacerfont · Pivagabine

|

|

|

D2/D3AR antagonists

|

Amisulpride · Sulpiride

|

|

|

D2/D3/D4R agonists

|

Piribedil · Pramipexole · Ropinirole · Rotigotine · Roxindole

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Agomelatine · Melatonin · Ramelteon · Tasimelteon |

|

|

NK1R antagonists

|

Aprepitant · Casopitant · Fosaprepitant · L-733,060 · Maropitant · Vestipitant

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PDE4 inhibitors

|

Mesembrine (Kanna) · Rolipram

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

dsrd (o, p, m, p, a, d, s), sysi/, spvo

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anxiolytics (N05B) |

|

| GABAA PAMs |

|

|

Adinazolam • Alprazolam • Bretazenil • Bromazepam • Camazepam • Chlordiazepoxide • Clobazam • Clonazepam • Clorazepate • Clotiazepam • Cloxazolam • Diazepam • Ethyl Loflazepate • Etizolam • Fludiazepam • Halazepam • Imidazenil • Ketazolam • Lorazepam • Medazepam • Nordazepam • Oxazepam • Pinazepam • Prazepam |

|

|

Carbamates

|

Emylcamate • Mebutamate • Meprobamate (Carisoprodol, Tybamate) • Phenprobamate • Procymate

|

|

|

Nonbenzodiazepines

|

Abecarnil • Adipiplon • Alpidem • CGS-9896 • CGS-20625 • Divaplon • ELB-139 • Fasiplon • GBLD-345 • Gedocarnil • L-838,417 • NS-2664 • NS-2710 • Ocinaplon • Pagoclone • Panadiplon • Pipequaline • RWJ-51204 • SB-205,384 • SL-651,498 • Taniplon • TP-003 • TP-13 • TPA-023 • Y-23684 • ZK-93423

|

|

|

Pyrazolopyridines

|

Cartazolate • Etazolate • ICI-190,622 • Tracazolate

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

| α2δ VDCC Blockers |

|

|

| 5-HT1A Agonists |

Azapirones: Buspirone • Gepirone • Tandospirone; Others: Flesinoxan • Oxaflozane

|

|

| H1 Antagonists |

Diphenylmethanes: Captodiame • Hydroxyzine; Others: Brompheniramine • Chlorpheniramine • Pheniramine

|

|

| CRH1 Antagonists |

Antalarmin • CP-154,526 • Pexacerfont • Pivagabine

|

|

| NK2 Antagonists |

GR-159,897 • Saredutant

|

|

| MCH1 antagonists |

ATC-0175 • SNAP-94847

|

|

| mGluR2/3 Agonists |

Eglumegad

|

|

| mGluR5 NAMs |

Fenobam

|

|

| TSPO agonists |

DAA-1097 • DAA-1106 • Emapunil • FGIN-127 • FGIN-143

|

|

| σ1 agonists |

Afobazole • Opipramol

|

|

| Others |

Benzoctamine • Carbetocin • Demoxytocin • Mephenoxalone • Mepiprazole • Oxanamide • Oxytocin • Promoxolane • Tofisopam • Trimetozine • WAY-267,464 |

|

#WHO-EM. ‡Withdrawn from market. Clinical trials: †Phase III. §Never to phase III

|

|

|

dsrd (o, p, m, p, a, d, s), sysi/, spvo

|

|

|

|

|

|

Serotonergics |

|

|

5-HT1 receptor ligands |

|

|

5-HT1A

|

Agonists: Azapirones: Alnespirone • Binospirone • Buspirone • Enilospirone • Eptapirone • Gepirone • Ipsapirone • Perospirone • Revospirone • Tandospirone • Tiospirone • Umespirone • Zalospirone; Antidepressants: Etoperidone • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Quetiapine • Ziprasidone; Ergolines: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • Methysergide • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • DMT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • Adatanserin • Befiradol • BMY-14802 • Cannabidiol • Dimemebfe • Ebalzotan • Eltoprazine • F-11,461 • F-12,826 • F-13,714 • F-14,679 • F-15,063 • F-15,599 • Flesinoxan • Flibanserin • Lesopitron • Lu AA21004 • LY-293,284 • LY-301,317 • MKC-242 • NBUMP • Osemozotan • Oxaflozane • Pardoprunox • Piclozotan • Rauwolscine • Repinotan • Roxindole • RU-24,969 • S 14,506 • S-14,671 • S-15,535 • Sarizotan • SSR-181,507 • Sunepitron • U-92016A • Urapidil • Vilazodone • Xaliproden • Yohimbine

Antagonists: Antipsychotics: Iloperidone • Risperidone • Sertindole; Beta blockers: Alprenolol • Cyanopindolol • Iodocyanopindolol • Oxprenolol • Pindobind • Pindolol • Propranolol • Tertatolol; Others: AV965 • BMY-7378 • CSP-2503 • Dotarizine • Flopropione • GR-46611 • Isamoltane • Lecozotan • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MPPF • NAN-190 • PRX-00023 • Robalzotan • S-15535 • SB-649915 • SDZ 216-525 • Spiperone • Spiramide • Spiroxatrine • UH-301 • WAY-100,135 • WAY-100,635 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

5-HT1B

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Methysergide; Piperazines: Eltoprazine • TFMPP; Triptans: Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CGS-12066A • CP-93,129 • CP-94,253 • CP-135,807 • RU-24969

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: AR-A000002 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Isamoltane • Metitepine/Methiothepin • SB-216,641 • SB-224,289 • SB-236,057 • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT1D

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Methysergide; Triptans: Almotriptan • Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Frovatriptan • Naratriptan • Rizatriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CP-135,807 • CP-286,601 • GR-46611 • L-694,247 • L-772,405 • PNU-109,291 • PNU-142,633

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: Alniditan • BRL-15572 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Ketanserin • LY-310,762 • LY-367,642 • LY-456,219 • LY-456,220 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • Yohimbine • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

5-HT1E

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Methysergide; Triptans: Eletriptan; Tryptamines: BRL-54443 • Tryptamine

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

5-HT1F

|

Agonists: Triptans: Eletriptan • Naratriptan • Sumatriptan; Tryptamines: 5-MT; Others: BRL-54443 • Lasmiditan • LY-334,370

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT2 receptor ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT2A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: ALD-52 • Ergonovine • Lisuride • LA-SS-Az • LSD • LSD-Pip • Lysergic acid 2-butyl amide • Methysergide; Phenethylamines: 25I-NBMD • 25I-NBOH • 25I-NBOMe • 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2CB-Ind • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • 2CBCB-NBOMe • 2CBFly-NBOMe • Bromo-DragonFLY • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline • TCB-2 • TFMFly; Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: AL-34662 • AL-37350A • Dimemebfe • Medifoxamine • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • RH-34

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Amperozide • Aripiprazole • Carpipramine • Clocapramine • Clozapine • Gevotroline • Iloperidone • Melperone • Mosapramine • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Others: 5-I-R91150 • AC-90179 • Adatanserin • Altanserin • AMDA • APD-215 • Blonanserin • Cinanserin • CSP-2503 • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eplivanserin • Esmirtazapine • Fananserin • Flibanserin • Ketanserin • KML-010 • Lubazodone • Mepiprazole • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Nantenine • Pimavanserin • Pizotifen • Pruvanserin • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • S-14,671 • Sarpogrelate • Setoperone • Spiperone • Spiramide • SR-46349B • Volinanserin • Xylamidine • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2B

|

Agonists: Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex; Phenethylamines: Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • Fenfluramine • MDA • MDMA • Norfenfluramine; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • α-Methyl-5-HT; Others: BW-723C86 • Cabergoline • mCPP • Pergolide • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175

Antagonists: Agomelatine • Asenapine • EGIS-7625 • Ketanserin • Lisuride • LY-272,015 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • PRX-08066 • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • RS-127,445 • Sarpogrelate • SB-200,646 • SB-204,741 • SB-206,553 • SB-215,505 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SDZ SER-082 • Tegaserod • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2C

|

Agonists: Phenethylamines: 2C-B • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline; Piperazines: Aripiprazole • mCPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: A-372,159 • AL-38022A • CP-809,101 • Dimemebfe • Lorcaserin• Medifoxamine • MK-212 • ORG-37,684 • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175 • Vabicaserin • WAY-629 • WAY-161,503 • YM-348

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Iloperidone • Melperone • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Agomelatine • Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Fluoxetine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Nortriptyline • Trazodone; Others: Adatanserin • Cinanserin • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eltoprazine • Esmirtazapine • FR-260,010 • Ketanserin • Ketotifen • Latrepirdine • Lu AA24530 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Methysergide • Pizotifen • Ritanserin • RS-102,221 • S-14,671 • SB-200,646 • SB-206,553 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SB-242,084 • SB-243,213 • SDZ SER-082 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT3

|

Agonists: Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-CT; Others: Chlorophenylbiguanide • Butanol • Ethanol • Halothane • Isoflurane • RS-56812 • SR-57,227 • SR-57,227-A • Toluene • Trichloroethane • Trichloroethanol • Trichloroethylene • YM-31636

Antagonists: Antiemetics: AS-8112 • Alosetron • Azasetron • Batanopride • Bemesetron • Cilansetron • Dazopride • Dolasetron • Granisetron • Lerisetron • Ondansetron • Palonosetron • Ramosetron • Renzapride • Tropisetron • Zacopride • Zatosetron; Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Olanzapine • Quetiapine; Tetracyclic antidepressants: Amoxapine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine; Others: CSP-2503 • ICS-205,930 • Lu AA21004 • Lu AA24530 • MDL-72,222 • Memantine • Nitrous Oxide • Ricasetron • Sevoflurane • Thujone • Xenon

|

|

|

5-HT4

|

Agonists: Gastroprokinetic Agents: Cinitapride • Cisapride • Dazopride • Metoclopramide • Mosapride • Prucalopride • Renzapride • Tegaserod • Zacopride; Others: 5-MT • BIMU-8 • CJ-033,466 • PRX-03140 • RS-67333 • RS-67506 • SL65.0155 • TD-5108

Antagonists: GR-113,808 • GR-125,487 • L-Lysine • Piboserod • RS-39604 • RS-67532 • SB-203,186

|

|

|

5-HT5A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Ergotamine • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT; Others: Valerenic Acid

Antagonists: Asenapine • Latrepirdine • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • SB-699,551

* Note that the 5-HT5B receptor is not functional in humans.

|

|

|

5-HT6

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • LSD • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-BT • 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • E-6801 • E-6837 • EMD-386,088 • EMDT • LY-586,713 • N-Methyl-5-HT • Tryptamine; Others: WAY-181,187 • WAY-208,466

Antagonists: Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Doxepin • Mianserin • Nortriptyline; Atypical antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Fluperlapine • Iloperidone • Olanzapine • Tiospirone; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: BGC20-760 • BVT-5182 • BVT-74316 • EGIS-12233 • GW-742,457 • Ketanserin • Latrepirdine • Lu AE58054 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MS-245 • PRX-07034 • Ritanserin • Ro 04-6790 • Ro 63-0563 • SB-258,585 • SB-271,046 • SB-357,134 • SB-399,885 • SB-742,457

|

|

|

5-HT7

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • AS-19 • Bifeprunox • LP-12 • LP-44 • RU-24,969 • Sarizotan

Antagonists: Lysergamides: 2-Bromo-LSD • Bromocriptine • Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Imipramine • Maprotiline • Mianserin; Atypical antipsychotics: Amisulpride • Aripiprazole • Clozapine • Olanzapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Tiospirone • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: Butaclamol • EGIS-12233 • Ketanserin • LY-215,840 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Pimozide • Ritanserin • SB-258,719 • SB-258,741 • SB-269,970 • SB-656,104 • SB-656,104-A • SB-691,673 • SLV-313 • SLV-314 • Spiperone • SSR-181,507

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

SERT

|

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Alaproclate • Citalopram • Dapoxetine • Desmethylcitalopram • Desmethylsertraline • Escitalopram • Femoxetine • Fluoxetine • Fluvoxamine • Indalpine • Ifoxetine • Litoxetine • Lu AA21004 • Lubazodone • Panuramine • Paroxetine • Pirandamine • RTI-353 • Seproxetine • Sertraline • Vilazodone • Zimelidine; Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Bicifadine • Desvenlafaxine • Duloxetine • Eclanamine • Levomilnacipran • Milnacipran • Sibutramine • Venlafaxine; Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (SNDRIs): Brasofensine • Diclofensine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • NS-2359 • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Tesofensine; Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): Amitriptyline • Butriptyline • Cianopramine • Clomipramine • Desipramine • Dosulepin • Doxepin • Imipramine • Lofepramine • Nortriptyline • Pipofezine • Protriptyline • Trimipramine; Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs): Amoxapine; Piperazines: Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antihistamines: Brompheniramine • Chlorpheniramine • Diphenhydramine • Mepyramine/Pyrilamine • Pheniramine • Tripelennamine; Opioids: Meperidine (Pethidine) • Methadone • Propoxyphene; Others: Cocaine • CP-39,332 • Cyclobenzaprine • Dextromethorphan • Dextrorphan • EXP-561 • Fezolamine • Mesembrine • Nefopam • PIM-35 • Pridefrine • Roxindole • SB-649,915 • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

VMAT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Aminoindanes: 5-IAI • ETAI • MDAI • MDMAI • MMAI • TAI; Aminotetralins: 6-CAT • 8-OH-DPAT • MDAT • MDMAT; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex • Clominorex • Fluminorex; Phenethylamines (also Amphetamines, Cathinones, Phentermines, etc): 2-Methyl-MDA • 4-CAB • 4-FA • 4-FMA • 4-HA • 4-MTA • 5-APDB • 5-Methyl-MDA • 6-APDB • 6-Methyl-MDA • Amiflamine • BDB • BOH • Brephedrone • Butylone • Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • Diethylcathinone • Dimethylcathinone • DMA • DMMA • EBDB • EDMA • Ethylone • Etolorex • Fenfluramine (Dexfenfluramine) • Flephedrone • IAP • IMP • Lophophine • MBDB • MDA • MDEA • MDHMA • MDMA • MDMPEA • MDOH • MDPEA • Mephedrone • Methedrone • Methylone • MMA • MMDA • MMDMA • NAP • Norfenfluramine • pBA • pCA • pIA • PMA • PMEA • PMMA • TAP; Piperazines: 2C-B-BZP • BZP • MBZP • mCPP • MDBZP • MeOPP • Mepiprazole • pFPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 4-Methyl-αET • 4-Methyl-αMT • 5-CT • 5-MeO-αET • 5-MeO-αMT • 5-MT • αET • αMT • DMT • Tryptamine (itself); Others: Indeloxazine • Tramadol • Viqualine

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

TPH

|

AGN-2979 • Fenclonine

|

|

|

AAAD

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

|

|

|

MAO

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A Selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity enhancers: BPAP • PPAP; Reuptake enhancers: Tianeptine

|

|

|

|

-citalopram-3D-sticks.png)

-citalopram-3D-sticks.png)

-citalopram.png)

-citalopram.png)