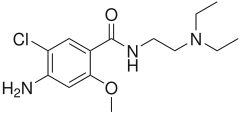

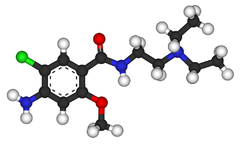

Metoclopramide

Metoclopramide (INN) (pronounced /ˌmɛtəˈklɒprəmaɪd/) is an antiemetic and gastroprokinetic agent. Thus it is primarily used to treat nausea and vomiting, and to facilitate gastric emptying in patients with gastroparesis. It is also a primary treatment for migraine headaches.

It is available under various trade names including Maxolon (Shire/Valeant), Reglan (Schwarz Pharma), Degan (Lek), Maxeran (Sanofi Aventis), Primperan (Sanofi Aventis), and Pylomid (Bosnalijek). It was protected under U.S. patent (3177252) until 6 April 1982.

Mode of action

Metoclopramide was first described by Dr.Louis Justin-Besançon and C. Laville in 1964.[1] It appears to bind to dopamine D2 receptors where it is a receptor antagonist, and is also a mixed 5-HT3 receptor antagonist/5-HT4 receptor agonist.

The anti-emetic action of metoclopramide is due to its antagonist activity at D2 receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) in the central nervous system (CNS)—this action prevents nausea and vomiting triggered by most stimuli.[2] At higher doses, 5-HT3 antagonist activity may also contribute to the anti-emetic effect.

The prokinetic activity of metoclopramide is mediated by muscarinic activity, D2 receptor antagonist activity and 5-HT4 receptor agonist activity.[3][4] The prokinetic effect itself may also contribute to the anti-emetic effect.

Clinical use

Antiemetic use

Metoclopramide 5mg tablets (Pliva).

Metoclopramide is commonly used to treat nausea and vomiting (emesis) associated with conditions including: emetogenic drugs, uremia, radiation sickness, malignancy, labor, and infection.[5][6] It is also used by itself or in combination with paracetamol (acetaminophen) (paracetamol/metoclopramide available in the UK as Paramax, and Australia as Metomax) or aspirin (MigraMax) for the relief of migraine.

It is considered ineffective in postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) at standard doses, and ineffective for motion sickness.[5][6] In nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy, it has been superseded by the more effective 5-HT3 antagonists (e.g. ondansetron).

It is also used for the prevention of nausea and vomiting when the patient is given an opiate, such as morphine.

Prokinetic use

Metoclopramide increases peristalsis of the jejunum and duodenum, increases tone and amplitude of gastric contractions, and relaxes the pyloric sphincter and duodenal bulb. These prokinetic effects make metoclopramide useful in the treatment of gastric stasis (e.g. after gastric surgery or diabetic gastroparesis), as an aid in gastrointestinal radiology by increasing transit in barium studies, and as an aid in difficult small intestinal intubation. It is also used in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD/GORD).

Other indications

By inhibiting the action of dopamine (prolactin-inhibiting hormone), metoclopramide has sometimes been used to stimulate lactation. It can also be used in the treatment of migraines in the setting of cutaneous allodynia, where it is more effective than triptans.[7]

Contraindications and precautions

Metoclopramide is contraindicated in phaeochromocytoma. It should be used with caution in Parkinson's disease since, as a dopamine antagonist, it may worsen symptoms. Long-term use should be avoided in patients with clinical depression as it may worsen mental state.[6] Also contraindicated with a suspected bowel obstruction.

Use in pregnancy

Metoclopramide has long been used in all stages of pregnancy with no evidence of harm to the mother or unborn baby.[8] A large cohort study of babies born to Israeli women exposed to metoclopramide during pregnancy found no evidence that the drug increases the risk of congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, or perinatal mortality.[9]

Metoclopramide crosses into breast milk.[8]

Adverse effects

Plastic ampoule of metoclopramide

Common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with metoclopramide therapy include: restlessness, drowsiness, dizziness, lassitude, and/or dystonic reactions. Infrequent ADRs include: headache, extrapyramidal effects such as oculogyric crisis, hypertension, hypotension, hyperprolactinaemia leading to galactorrhoea, diarrhoea, constipation, and/or depression. Rare but serious ADRs associated with metoclopramide therapy include: agranulocytosis, supraventricular tachycardia, hyperaldosteronism, neuroleptic malignant syndrome and/or tardive dyskinesia.[6] Dystonic reactions are usually treated with benztropine or procyclidine.

The risk of extrapyramidal effects is increased in young adults (<20 years) and children, and with high-dose or prolonged therapy.[5][6] Tardive dyskinesias may be persistent and irreversible in some patients. In 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration required all manufacturers of metoclopramide to issue a black box warning regarding the risk of tardive dyskinesia with chronic or high-dose use of the drug.[10]

Veterinary use

Metoclopramide is also used in animals. It is commonly used to prevent vomiting in cats and dogs. It is also used as a gut stimulant in rabbits.

See also

- Benzamide, the chemical class to which metoclopramide belongs

- Bromopride, the bromo- analogue of metoclopramide

- Cisapride, a benzamide with a different mechanism of action

- Itopride, a newer benzamide with effects similar to those of metoclopramide

References

- ↑ Justin-Besançon L, Laville C. Action antiémétique du métoclopramide vis-à-vis de l'apomorphine et de l'hydergine [Antiemetic action of metoclopramide with respect to apomorphine and hydergine]. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil 1964;158:723–7. PMID 14186927.

- ↑ Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Moore PK. Pharmacology. 5th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. ISBN 0-443-07145-4

- ↑ Sweetman S, editor. Martindale: The complete drug reference. 34th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2004. ISBN 0-85369-550-4

- ↑ Tonini M, Candura SM, Messori E, Rizzi CA. Therapeutic potential of drugs with mixed 5-HT4 agonist/5-HT3 antagonist action in the control of emesis. Pharmacol Res 1995;31(5):257-60. PMID 7479521

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Maxolon (Australian Approved Product Information). Auburn (NSW): Valeant Pharmaceuticals Australasia; 2000.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3

- ↑ Snow V, Weiss K, Wall EM, Mottur-Pilson C. Pharmacologic management of acute attacks of migraine and prevention of migraine headache. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:840-9. [PMID: 12435222]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. ISBN 0-7817-7876-X. Retrieved on June 11, 2009.

- ↑ Matok I, Gorodischer R, Koren G, Sheiner E, Wiznitzer A, Levy A. The safety of metoclopramide use in the first trimester of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2009;360(24):2528–35.

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (February 26, 2009). "FDA requires boxed warning and risk mitigation strategy for metoclopramide-containing drugs". Press release. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm149533.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-11. Lay summary – WebMD (February 27, 2009).

Further reading

- Brenner GM. Pharmacology. London: W B Saunders; 2000 ISBN 0-7216-7757-6

- Canadian Pharmacists Association. Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties. 25th ed. Toronto: Webcom; 2000. ISBN 0-919115-76-4

- Practical Gastroenterology May 2004 Recognition of Movement Disorders and Extrapyramidal side effects - would you recognize them if you see them?. Available on practicalgastro.com

|

Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disorders (A03) |

|

Drugs for

functional bowel disorders |

|

Antimuscarinics

|

|

Tertiary

amino group

|

Oxyphencyclimine · Camylofin · Mebeverine · Trimebutine · Rociverine · Dicycloverine · Dihexyverine · Difemerine · Piperidolate

|

|

|

Quaternary ammonium

compounds

|

Benzilone · Mepenzolate · Pipenzolate · Glycopyrronium · Oxyphenonium · Penthienate · Methantheline · Propantheline · Otilonium bromide · Tridihexethyl · Isopropamide · Hexocyclium · Poldine · Bevonium · Diphemanil · Tiemonium iodide · Prifinium bromide · Timepidium bromide · Fenpiverinium

|

|

|

|

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors

|

Papaverine · Drotaverine · Moxaverine

|

|

|

Acting on serotonin receptors

|

5-HT3 antagonists (Alosetron, Cilansetron) · 5-HT4 agonists (Mosapride, Prucalopride, Tegaserod)

|

|

|

Other

|

Fenpiprane · Diisopromine · Chlorbenzoxamine · Pinaverium · Fenoverine · Idanpramine · Proxazole · Alverine · Trepibutone · Isometheptene · Caroverine · Phloroglucinol · Silicones · Trimethyldiphenylpropylamine |

|

|

Belladonna and derivatives

(antimuscarinics) |

tertiary amines: Atropine · Hyoscyamine

quaternary ammonium compounds: Scopolamine (Butylscopolamine, Methylscopolamine) · Methylatropine · Fentonium · Cimetropium bromide

|

|

| Propulsives |

primarily dopamine antagonists (Metoclopramide/Bromopride, Clebopride, Domperidone, Alizapride) · 5-HT4 agonists (Cinitapride · Cisapride)

|

|

|

|

anat(t, g, p)/phys/devp/cell/

|

|

proc, drug(A2A/2B/3/4//6/7/14/16), blte

|

|

|

|

|

Dopaminergics |

|

|

Receptor ligands |

|

|

Agonists

|

Adamantanes: Amantadine • Memantine • Rimantadine; Aminotetralins: 7-OH-DPAT • 8-OH-PBZI • Rotigotine • UH-232; Benzazepines: 6-Br-APB • Fenoldopam • SKF-38,393 • SKF-77,434 • SKF-81,297 • SKF-82,958 • SKF-83,959; Ergolines: Bromocriptine • Cabergoline • Dihydroergocryptine • Lisuride • LSD • Pergolide; Dihydrexidine derivatives: 2-OH-NPA • A-86,929 • Ciladopa • Dihydrexidine • Dinapsoline • Dinoxyline • Doxanthrine; Others: A-68,930 • A-77,636 • A-412,997 • ABT-670 • ABT-724 • Aplindore • Apomorphine • Aripiprazole • Bifeprunox • BP-897 • CY-208,243 • Dizocilpine • Etilevodopa • Flibanserin • Ketamine • Melevodopa • Modafinil • Pardoprunox • Phencyclidine • PD-128,907 • PD-168,077 • PF-219,061 • Piribedil • Pramipexole • Propylnorapomorphine • Pukateine • Quinagolide • Quinelorane • Quinpirole • RDS-127 • Ro10-5824 • Ropinirole • Rotigotine • Roxindole • Salvinorin A • SKF-89,145 • Sumanirole • Terguride • Umespirone • WAY-100,635

|

|

|

Antagonists

|

Typical antipsychotics: Acepromazine • Azaperone • Benperidol • Bromperidol • Clopenthixol • Chlorpromazine • Chlorprothixene • Droperidol • Flupentixol • Fluphenazine • Fluspirilene • Haloperidol • Loxapine • Mesoridazine • Methotrimeprazine • Nemonapride • Penfluridol • Perazine • Periciazine • Perphenazine • Pimozide • Prochlorperazine • Promazine • Sulforidazine • Sulpiride • Sultopride • Thioridazine • Thiothixene • Trifluoperazine • Triflupromazine • Trifluperidol • Zuclopenthixol; Atypical antipsychotics: Amisulpride • Asenapine • Blonanserin • Carpipramine • Clocapramine • Clozapine • Gevotroline • Iloperidone • Lurasidone • Melperone • Molindone • Mosapramine • Ocaperidone • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Perospirone • Piquindone • Quetiapine • Remoxipride • Risperidone • Sertindole • Tiospirone • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Antiemetics: AS-8112 • Alizapride • Bromopride • Clebopride • Domperidone • Metoclopramide • Thiethylperazine; Others: Amoxapine • Buspirone • Butaclamol • Ecopipam • EEDQ • Eticlopride • Fananserin • L-745,870 • Nafadotride • Nuciferine • PNU-99,194 • Raclopride • Sarizotan • SB-277,011-A • SCH-23,390 • SKF-83,566 • SKF-83,959 • Sonepiprazole • Spiperone • Spiroxatrine • Stepholidine • Tetrahydropalmatine • Tiapride • UH-232 • Yohimbine

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

DAT inhibitors

|

Piperazines: DBL-583 • GBR-12,935 • Nefazodone • Vanoxerine; Piperidines: BTCP • Desoxypipradrol • Dextromethylphenidate • Difemetorex • Ethylphenidate • Methylnaphthidate • Methylphenidate • Phencyclidine • Pipradrol; Pyrrolidines: Diphenylprolinol • Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) • Naphyrone • Prolintane • Pyrovalerone; Tropanes: β-CPPIT • Altropane • Brasofensine • CFT • Cocaine • Dichloropane • Difluoropine • FE-β-CPPIT • FP-β-CPPIT • Ioflupane ( 123I) • Iometopane • RTI-112 • RTI-113 • RTI-121 • RTI-126 • RTI-150 • RTI-177 • RTI-229 • RTI-336 • Tenocyclidine • Tesofensine • Troparil • Tropoxane • WF-11 • WF-23 • WF-31 • WF-33; Others: Adrafinil • Armodafinil • Amfonelic acid • Amineptine • Benzatropine (Benztropine) • Bromantane • BTQ • BTS-74,398 • Bupropion (Amfebutamone) • Ciclazindol • Diclofensine • Dimethocaine • Diphenylpyraline • Dizocilpine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • Etybenzatropine (Ethylbenztropine) • EXP-561 • Fencamine • Fencamfamine • Fezolamine • GYKI-52,895 • Indatraline • Ketamine • Lefetamine • Levophacetoperane • LR-5182 • Manifaxine • Mazindol • Medifoxamine • Mesocarb • Modafinil • Nefopam • Nomifensine • NS-2359 • O-2172 • Pridefrine • Propylamphetamine • Radafaxine • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Sertraline • Sibutramine • Tametraline • Tripelennamine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Morpholines: Fenbutrazate • Morazone • Phendimetrazine • Phenmetrazine; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex (4-MAR, 4-MAX) • Aminorex • Clominorex • Cyclazodone • Fenozolone • Fluminorex • Pemoline • Thozalinone; Phenethylamines (also amphetamines, cathinones, phentermines, etc): 2-Hydroxyphenethylamine (2-OH-PEA) • 4-CAB • 4-Methylamphetamine (4-MA) • 4-Methylmethamphetamine (4-MMA) • Alfetamine • Amfecloral • Amfepentorex • Amfepramone • Amphetamine ( Dextroamphetamine, Levoamphetamine) • Amphetaminil • β-Methylphenethylamine (β-Me-PEA) • Benzodioxolylbutanamine (BDB) • Benzodioxolylhydroxybutanamine (BOH) • Benzphetamine • Buphedrone • Butylone • Cathine • Cathinone • Clobenzorex • Clortermine • D-Deprenyl • Dimethoxyamphetamine (DMA) • Dimethoxymethamphetamine (DMMA) • Dimethylamphetamine • Dimethylcathinone (Dimethylpropion, metamfepramone) • Ethcathinone (Ethylpropion) • Ethylamphetamine • Ethylbenzodioxolylbutanamine (EBDB) • Ethylone • Famprofazone • Fenethylline • Fenproporex • Flephedrone • Fludorex • Furfenorex • Hordenine • Lophophine (Homomyristicylamine) • Mefenorex • Mephedrone • Methamphetamine (Desoxyephedrine, Methedrine; Dextromethamphetamine, Levomethamphetamine) • Methcathinone (Methylpropion) • Methedrone • Methoxymethylenedioxyamphetamine (MMDA) • Methoxymethylenedioxymethamphetamine (MMDMA) • Methylbenzodioxolylbutanamine (MBDB) • Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA, tenamfetamine) • Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) • Methylenedioxyhydroxyamphetamine (MDOH) • Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) • Methylenedioxymethylphenethylamine (MDMPEA, homarylamine) • Methylenedioxyphenethylamine (MDPEA, homopiperonylamine) • Methylone • Ortetamine • Parabromoamphetamine (PBA) • Parachloroamphetamine (PCA) • Parafluoroamphetamine (PFA) • Parafluoromethamphetamine (PFMA) • Parahydroxyamphetamine (PHA) • Paraiodoamphetamine (PIA) • Paredrine (Norpholedrine, Oxamphetamine) • Phenethylamine (PEA) • Pholedrine • Phenpromethamine • Prenylamine • Propylamphetamine • Tiflorex (Flutiorex) • Tyramine (TRA) • Xylopropamine • Zylofuramine; Piperazines: 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-bromobenzylpiperazine (2C-B-BZP) • Benzylpiperazine (BZP) • Methoxyphenylpiperazine (MeOPP, paraperazine) • Methylbenzylpiperazine (MBZP) • Methylenedioxybenzylpiperazine (MDBZP, piperonylpiperazine); Others: 2-Amino-1,2-dihydronaphthalene (2-ADN) • 2-Aminoindane (2-AI) • 2-Aminotetralin (2-AT) • 4-Benzylpiperidine (4-BP) • 5-IAI • Clofenciclan • Cyclopentamine • Cypenamine • Cyprodenate • Feprosidnine • Gilutensin • Heptaminol • Hexacyclonate • Indanylaminopropane (IAP) • Indanorex • Isometheptene • Methylhexanamine • Naphthylaminopropane (NAP) • Octodrine • Phthalimidopropiophenone • Propylhexedrine (Levopropylhexedrine) • Tuaminoheptane (Tuamine)

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

PAH inhibitors

|

3,4-Dihydroxystyrene

|

|

|

TH inhibitors

|

3-Iodotyrosine • Aquayamycin • Bulbocapnine • Metirosine • Oudenone

|

|

|

AAAD / DDC inhibitors

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima; MAO-B selective: D-Deprenyl • L-Deprenyl (Selegiline) • Ladostigil • Lazabemide • Milacemide • Mofegiline • Pargyline • Rasagiline

|

|

|

COMT inhibitors

|

Entacapone • Tolcapone

|

|

|

DBH inhibitors

|

Bupicomide • Disulfiram • Dopastin • Fusaric acid • Nepicastat • Phenopicolinic acid • Tropolone

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity Enhancers: Benzofuranylpropylaminopentane (BPAP) • Phenylpropylaminopentane (PPAP); Toxins: Oxidopamine (6-Hydroxydopamine)

|

|

|

|

|

Serotonergics |

|

|

5-HT1 receptor ligands |

|

|

5-HT1A

|

Agonists: Azapirones: Alnespirone • Binospirone • Buspirone • Enilospirone • Eptapirone • Gepirone • Ipsapirone • Perospirone • Revospirone • Tandospirone • Tiospirone • Umespirone • Zalospirone; Antidepressants: Etoperidone • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Quetiapine • Ziprasidone; Ergolines: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • Methysergide • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • DMT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • Adatanserin • Befiradol • BMY-14802 • Cannabidiol • Dimemebfe • Ebalzotan • Eltoprazine • F-11,461 • F-12,826 • F-13,714 • F-14,679 • F-15,063 • F-15,599 • Flesinoxan • Flibanserin • Lesopitron • Lu AA21004 • LY-293,284 • LY-301,317 • MKC-242 • NBUMP • Osemozotan • Oxaflozane • Pardoprunox • Piclozotan • Rauwolscine • Repinotan • Roxindole • RU-24,969 • S 14,506 • S-14,671 • S-15,535 • Sarizotan • SSR-181,507 • Sunepitron • U-92016A • Urapidil • Vilazodone • Xaliproden • Yohimbine

Antagonists: Antipsychotics: Iloperidone • Risperidone • Sertindole; Beta blockers: Alprenolol • Cyanopindolol • Iodocyanopindolol • Oxprenolol • Pindobind • Pindolol • Propranolol • Tertatolol; Others: AV965 • BMY-7378 • CSP-2503 • Dotarizine • Flopropione • GR-46611 • Isamoltane • Lecozotan • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MPPF • NAN-190 • PRX-00023 • Robalzotan • S-15535 • SB-649915 • SDZ 216-525 • Spiperone • Spiramide • Spiroxatrine • UH-301 • WAY-100,135 • WAY-100,635 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

5-HT1B

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Methysergide; Piperazines: Eltoprazine • TFMPP; Triptans: Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CGS-12066A • CP-93,129 • CP-94,253 • CP-135,807 • RU-24969

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: AR-A000002 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Isamoltane • Metitepine/Methiothepin • SB-216,641 • SB-224,289 • SB-236,057 • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT1D

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Methysergide; Triptans: Almotriptan • Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Frovatriptan • Naratriptan • Rizatriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CP-135,807 • CP-286,601 • GR-46611 • L-694,247 • L-772,405 • PNU-109,291 • PNU-142,633

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: Alniditan • BRL-15572 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Ketanserin • LY-310,762 • LY-367,642 • LY-456,219 • LY-456,220 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • Yohimbine • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

5-HT1E

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Methysergide; Triptans: Eletriptan; Tryptamines: BRL-54443 • Tryptamine

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

5-HT1F

|

Agonists: Triptans: Eletriptan • Naratriptan • Sumatriptan; Tryptamines: 5-MT; Others: BRL-54443 • Lasmiditan • LY-334,370

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT2 receptor ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT2A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: ALD-52 • Ergonovine • Lisuride • LA-SS-Az • LSD • LSD-Pip • Lysergic acid 2-butyl amide • Methysergide; Phenethylamines: 25I-NBMD • 25I-NBOH • 25I-NBOMe • 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2CB-Ind • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • 2CBCB-NBOMe • 2CBFly-NBOMe • Bromo-DragonFLY • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline • TCB-2 • TFMFly; Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: AL-34662 • AL-37350A • Dimemebfe • Medifoxamine • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • RH-34

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Amperozide • Aripiprazole • Carpipramine • Clocapramine • Clozapine • Gevotroline • Iloperidone • Melperone • Mosapramine • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Others: 5-I-R91150 • AC-90179 • Adatanserin • Altanserin • AMDA • APD-215 • Blonanserin • Cinanserin • CSP-2503 • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eplivanserin • Esmirtazapine • Fananserin • Flibanserin • Ketanserin • KML-010 • Lubazodone • Mepiprazole • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Nantenine • Pimavanserin • Pizotifen • Pruvanserin • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • S-14,671 • Sarpogrelate • Setoperone • Spiperone • Spiramide • SR-46349B • Volinanserin • Xylamidine • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2B

|

Agonists: Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex; Phenethylamines: Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • Fenfluramine • MDA • MDMA • Norfenfluramine; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • α-Methyl-5-HT; Others: BW-723C86 • Cabergoline • mCPP • Pergolide • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175

Antagonists: Agomelatine • Asenapine • EGIS-7625 • Ketanserin • Lisuride • LY-272,015 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • PRX-08066 • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • RS-127,445 • Sarpogrelate • SB-200,646 • SB-204,741 • SB-206,553 • SB-215,505 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SDZ SER-082 • Tegaserod • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2C

|

Agonists: Phenethylamines: 2C-B • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline; Piperazines: Aripiprazole • mCPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: A-372,159 • AL-38022A • CP-809,101 • Dimemebfe • Lorcaserin• Medifoxamine • MK-212 • ORG-37,684 • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175 • Vabicaserin • WAY-629 • WAY-161,503 • YM-348

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Iloperidone • Melperone • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Agomelatine • Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Fluoxetine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Nortriptyline • Trazodone; Others: Adatanserin • Cinanserin • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eltoprazine • Esmirtazapine • FR-260,010 • Ketanserin • Ketotifen • Latrepirdine • Lu AA24530 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Methysergide • Pizotifen • Ritanserin • RS-102,221 • S-14,671 • SB-200,646 • SB-206,553 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SB-242,084 • SB-243,213 • SDZ SER-082 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT3

|

Agonists: Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-CT; Others: Chlorophenylbiguanide • Butanol • Ethanol • Halothane • Isoflurane • RS-56812 • SR-57,227 • SR-57,227-A • Toluene • Trichloroethane • Trichloroethanol • Trichloroethylene • YM-31636

Antagonists: Antiemetics: AS-8112 • Alosetron • Azasetron • Batanopride • Bemesetron • Cilansetron • Dazopride • Dolasetron • Granisetron • Lerisetron • Ondansetron • Palonosetron • Ramosetron • Renzapride • Tropisetron • Zacopride • Zatosetron; Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Olanzapine • Quetiapine; Tetracyclic antidepressants: Amoxapine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine; Others: CSP-2503 • ICS-205,930 • Lu AA21004 • Lu AA24530 • MDL-72,222 • Memantine • Nitrous Oxide • Ricasetron • Sevoflurane • Thujone • Xenon

|

|

|

5-HT4

|

Agonists: Gastroprokinetic Agents: Cinitapride • Cisapride • Dazopride • Metoclopramide • Mosapride • Prucalopride • Renzapride • Tegaserod • Zacopride; Others: 5-MT • BIMU-8 • CJ-033,466 • PRX-03140 • RS-67333 • RS-67506 • SL65.0155 • TD-5108

Antagonists: GR-113,808 • GR-125,487 • L-Lysine • Piboserod • RS-39604 • RS-67532 • SB-203,186

|

|

|

5-HT5A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Ergotamine • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT; Others: Valerenic Acid

Antagonists: Asenapine • Latrepirdine • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • SB-699,551

* Note that the 5-HT5B receptor is not functional in humans.

|

|

|

5-HT6

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • LSD • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-BT • 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • E-6801 • E-6837 • EMD-386,088 • EMDT • LY-586,713 • N-Methyl-5-HT • Tryptamine; Others: WAY-181,187 • WAY-208,466

Antagonists: Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Doxepin • Mianserin • Nortriptyline; Atypical antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Fluperlapine • Iloperidone • Olanzapine • Tiospirone; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: BGC20-760 • BVT-5182 • BVT-74316 • EGIS-12233 • GW-742,457 • Ketanserin • Latrepirdine • Lu AE58054 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MS-245 • PRX-07034 • Ritanserin • Ro 04-6790 • Ro 63-0563 • SB-258,585 • SB-271,046 • SB-357,134 • SB-399,885 • SB-742,457

|

|

|

5-HT7

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • AS-19 • Bifeprunox • LP-12 • LP-44 • RU-24,969 • Sarizotan

Antagonists: Lysergamides: 2-Bromo-LSD • Bromocriptine • Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Imipramine • Maprotiline • Mianserin; Atypical antipsychotics: Amisulpride • Aripiprazole • Clozapine • Olanzapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Tiospirone • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: Butaclamol • EGIS-12233 • Ketanserin • LY-215,840 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Pimozide • Ritanserin • SB-258,719 • SB-258,741 • SB-269,970 • SB-656,104 • SB-656,104-A • SB-691,673 • SLV-313 • SLV-314 • Spiperone • SSR-181,507

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

SERT

|

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Alaproclate • Citalopram • Dapoxetine • Desmethylcitalopram • Desmethylsertraline • Escitalopram • Femoxetine • Fluoxetine • Fluvoxamine • Indalpine • Ifoxetine • Litoxetine • Lu AA21004 • Lubazodone • Panuramine • Paroxetine • Pirandamine • RTI-353 • Seproxetine • Sertraline • Vilazodone • Zimelidine; Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Bicifadine • Desvenlafaxine • Duloxetine • Eclanamine • Levomilnacipran • Milnacipran • Sibutramine • Venlafaxine; Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (SNDRIs): Brasofensine • Diclofensine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • NS-2359 • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Tesofensine; Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): Amitriptyline • Butriptyline • Cianopramine • Clomipramine • Desipramine • Dosulepin • Doxepin • Imipramine • Lofepramine • Nortriptyline • Pipofezine • Protriptyline • Trimipramine; Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs): Amoxapine; Piperazines: Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antihistamines: Brompheniramine • Chlorpheniramine • Diphenhydramine • Mepyramine/Pyrilamine • Pheniramine • Tripelennamine; Opioids: Meperidine (Pethidine) • Methadone • Propoxyphene; Others: Cocaine • CP-39,332 • Cyclobenzaprine • Dextromethorphan • Dextrorphan • EXP-561 • Fezolamine • Mesembrine • Nefopam • PIM-35 • Pridefrine • Roxindole • SB-649,915 • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

VMAT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Aminoindanes: 5-IAI • ETAI • MDAI • MDMAI • MMAI • TAI; Aminotetralins: 6-CAT • 8-OH-DPAT • MDAT • MDMAT; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex • Clominorex • Fluminorex; Phenethylamines (also Amphetamines, Cathinones, Phentermines, etc): 2-Methyl-MDA • 4-CAB • 4-FA • 4-FMA • 4-HA • 4-MTA • 5-APDB • 5-Methyl-MDA • 6-APDB • 6-Methyl-MDA • Amiflamine • BDB • BOH • Brephedrone • Butylone • Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • Diethylcathinone • Dimethylcathinone • DMA • DMMA • EBDB • EDMA • Ethylone • Etolorex • Fenfluramine (Dexfenfluramine) • Flephedrone • IAP • IMP • Lophophine • MBDB • MDA • MDEA • MDHMA • MDMA • MDMPEA • MDOH • MDPEA • Mephedrone • Methedrone • Methylone • MMA • MMDA • MMDMA • NAP • Norfenfluramine • pBA • pCA • pIA • PMA • PMEA • PMMA • TAP; Piperazines: 2C-B-BZP • BZP • MBZP • mCPP • MDBZP • MeOPP • Mepiprazole • pFPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 4-Methyl-αET • 4-Methyl-αMT • 5-CT • 5-MeO-αET • 5-MeO-αMT • 5-MT • αET • αMT • DMT • Tryptamine (itself); Others: Indeloxazine • Tramadol • Viqualine

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

TPH

|

AGN-2979 • Fenclonine

|

|

|

AAAD

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

|

|

|

MAO

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A Selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity enhancers: BPAP • PPAP; Reuptake enhancers: Tianeptine

|

|

|

|