Estradiol

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

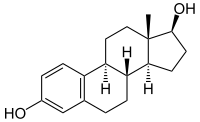

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (17β)-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 50-28-2 57-91-0 (±) |

| ATC code | G03CA03 |

| PubChem | CID 5757 |

| IUPHAR ligand | 1012 |

| DrugBank | DB00783 |

| ChemSpider | 5554 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C18H24O2 |

| Mol. mass | 272.38 |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| Synonyms | (8R,9S,13S,14S,17S)-13-methyl-6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-decahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,17-diol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 97-99% is bound |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Half-life | ~ 13 h |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | X (USA) |

| Legal status | S4 (Au), POM (UK), ℞-only (U.S.) |

| Routes | Oral, transdermal |

| |

|

Estradiol (E2 or 17β-estradiol) (also oestradiol) is a sex hormone. Estradiol is the predominant sex hormone present in females. It is also present in males, and at a higher level because it is being constantly produced. In females it is only produced 3 out of 30 days of the cycle. It represents the major estrogen in humans. Estradiol has not only a critical impact on reproductive and sexual functioning, but also affects other organs including the bones.

Contents |

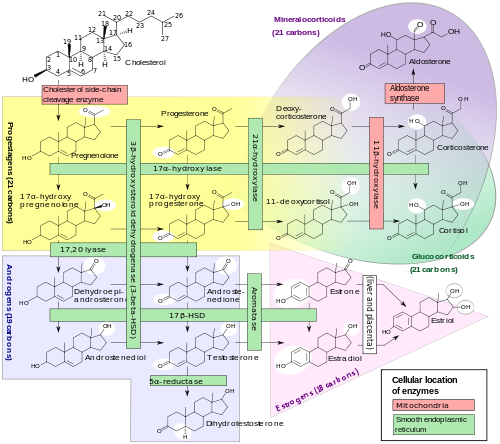

Synthesis

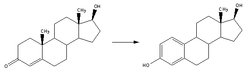

Estradiol, like other steroids, is derived from cholesterol. After side chain cleavage and utilizing the delta-5 pathway or the delta-4 pathway, androstenedione is the key intermediary. A fraction of the androstenedione is converted to testosterone, which in turn undergoes conversion to estradiol by an enzyme called aromatase. In an alternative pathway, androstenedione is "aromatized" to estrone, which is subsequently converted to estradiol.

Production

During the reproductive years, most estradiol in women is produced by the granulosa cells of the ovaries by the aromatization of androstenedione (produced in the theca folliculi cells) to estrone, followed by conversion of estrone to estradiol by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Smaller amounts of estradiol are also produced by the adrenal cortex, and (in men), by the testes.

Estradiol is produced not only in the gonads: In both sexes, precursor hormones, to be specific testosterone, are converted by aromatization to estradiol. In particular, fat cells are active to convert precursors to estradiol, and will continue to do so even after menopause. Estradiol is also produced in the brain and in arterial walls.

Mechanism of action

Estradiol enters cells freely and interacts with a cytoplasmic target cell receptor. After the estrogen receptor has bound its ligand, estradiol can enter the nucleus of the target cell, and regulate gene transcription, which leads to formation of messenger RNA. The mRNA interacts with ribosomes to produce specific proteins that express the effect of estradiol upon the target cell.

Estradiol binds well to both estrogen receptors, ERα, and ERβ, in contrast to certain other estrogens, notably medications that preferentially act on one of these receptors. These medications are called selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs.

Estradiol is the most potent naturally-occurring estrogen.

Recently there has been speculation about the membrane estrogen receptor ERX.

Metabolism

In plasma, estradiol is largely bound to sex hormone-binding globulin, also to albumin. Only a fraction of 2.21% (+/- 0.04%) is free and biologically active, the percentage remaining constant throughout the menstrual cycle.[1] Deactivation includes conversion to less-active estrogens such as estrone and estriol. Estriol is the major urinary metabolite. Estradiol is conjugated in the liver by sulfate and glucuronide formation and, as such, excreted via the kidneys. Some of the water-soluble conjugates are excreted via the bile duct, and partly reabsorbed after hydrolysis from the intestinal tract. This enterohepatic circulation contributes to maintaining estradiol levels.

Measurement

Serum estradiol measurement in women reflects primarily the activity of the ovaries. As such, they are useful in the detection of baseline estrogen in women with amenorrhea or menstrual dysfunction and to detect the state of hypoestrogenicity and menopause. Furthermore, estrogen monitoring during fertility therapy assesses follicular growth and is useful in monitoring the treatment. Estrogen-producing tumors will demonstrate persistent high levels of estradiol and other estrogens. In precocious puberty, estradiol levels are inappropriately increased.

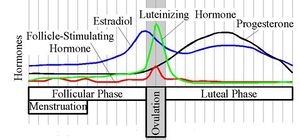

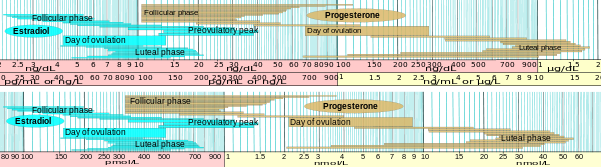

In the normal menstrual cycle, estradiol levels measure typically <50 pg/ml at menstruation, rise with follicular development (peak: 200 pg/ml), drop briefly at ovulation, and rise again during the luteal phase for a second peak. At the end of the luteal phase, estradiol levels drop to their menstrual levels unless there is a pregnancy.

During pregnancy, estrogen levels, including estradiol, rise steadily toward term. The source of these estrogens is the placenta, which aromatizes prohormones produced in the fetal adrenal gland.

Effects

Female reproduction

In the female, estradiol acts as a growth hormone for tissue of the reproductive organs, supporting the lining of the vagina, the cervical glands, the endometrium, and the lining of the fallopian tubes. It enhances growth of the myometrium. Estradiol appears necessary to maintain oocytes in the ovary. During the menstrual cycle, estradiol that is produced by the growing follicle triggers, via a positive feedback system, the hypothalamic-pituitary events that lead to the luteinizing hormone surge, inducing ovulation. In the luteal phase estradiol, in conjunction with progesterone, prepares the endometrium for implantation. During pregnancy, estradiol increases due to placental production. In baboons, blocking of estrogen production leads to pregnancy loss, suggesting that estradiol has a role in the maintenance of pregnancy. Research is investigating the role of estrogens in the process of initiation of labor.

Sexual development

The development of secondary sex characteristics in women is driven by estrogens, to be specific, estradiol. These changes are initiated at the time of puberty, most enhanced during the reproductive years, and become less pronounced with declining estradiol support after the menopause. Thus, estradiol enhances breast development, and is responsible for changes in the body shape, affecting bones, joints, fat deposition. Fat structure and skin composition are modified by estradiol.

Male reproduction

The effect of estradiol (and estrogens) upon male reproduction is complex. Estradiol is produced in the Sertoli cells of the testes. There is evidence that estradiol is designed to prevent apoptosis of male sperm cells.[2]

Several studies have noted that sperm counts have been declining in many parts of the world and it has been postulated that this may be related to estrogen exposure in the environment.[3] Suppression of estradiol production in a subpopulation of subfertile men may improve the semen analysis.[4]

Males with sex chromosome genetic conditions such as Klinefelters Syndrome will have a higher level of estradiol.

Bone

There is ample evidence that estradiol has a profound effect on bone. Individuals without estradiol (or other estrogens) will become tall and eunuchoid as epiphysieal closure is delayed or may not take place. Bone structure is affected resulting in early osteopenia and osteoporosis.[5] Also, women past menopause experience an accelerated loss of bone mass due to a relative estrogen deficiency.

Liver

Estradiol has complex effects on the liver. It can lead to cholestasis. It affects the production of multiple proteins including lipoproteins, binding proteins, and proteins responsible for blood clotting.

Brain

Estrogens can be produced in the brain from steroid precursors. As antioxidants, they have been found to have neuroprotective function.[6]

The positive and negative feedback loop of the menstrual cycle involve ovarian estradiol as the link to the hypothalamic-pituitary system to regulate gonadotropins.

Estrogen is considered to play a significant role in women’s mental health, with links suggested between the hormone, mood and well-being. Sudden drops or fluctuations in, or long periods of sustained low levels of estrogen may be correlated with significant mood-lowering. Clinical recovery from depression postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause was shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized and/or restored.[7][8]

Blood vessels

Estrogen affects certain blood vessels. Improvement in arterial blood flow has been demonstrated in coronary arteries.[9]

Oncogene

Estrogen is suspected to activate certain oncogenes, as it supports certain cancers, notably breast cancer and cancer of the uterine lining. In addition, there are several benign gynecologic conditions that are dependent on estrogen, such as endometriosis, leiomyomata uteri, and uterine bleeding..

Pregnancy

The effect of estradiol, together with estrone and estriol, in pregnancy is less clear. They may promote uterine blood flow, myometrial growth, sitmulate breast growth and at term, promote cervical softening and expression of myometrial oxytocin receptors.

Role in sex differentiation of the brain

One of the fascinating twists to mammalian sex differentiation is that estradiol is one of the two active metabolites of testosterone in males (the other being dihydrotestosterone), and since fetuses of both sexes are exposed to similarly high levels of maternal estradiol, this source cannot have a significant impact on prenatal sex differentiation. Estradiol cannot be transferred readily from the circulation into the brain, whereas testosterone can; thus sex differentiation can be caused by the testosterone in the brain of most male mammals, including humans, aromatizing in significant amounts into estradiol. There is also now evidence that the programming of adult male sexual behavior in animals is largely dependent on estradiol produced in the central nervous system during prenatal life and early infancy from testosterone.[10] However, it is not yet known whether this process plays a minimal or significant part in human sexual behaviors although evidence from other mammals tends to indicate that it does.[11]

Recently, it was discovered that volumes of sexually dimorphic brain structures in phenotypical males changed to approximate those of typical female brain structures when exposed to estradiol over a period of months.[12] This would suggest that estradiol has a significant part to play in sex differentiation of the brain, both pre-natal and throughout life.

Estradiol medication

Estrogen is marketed in a number of ways to address issues of hypoestrogenism. Thus there are oral, transdermal, topical, injectable, and vaginal preparations. Furthermore, the estradiol molecule may be linked to an alkyl group at C3 position to facilitate the administration. Such modifications give rise to estradiol acetate (oral and vaginal applications) and to estradiol cyprionate (injectable).

Oral preparations are not necessarily predictably absorbed and subject to a first pass through the liver, where they can be metabolized and also initiate unwanted side-effects. Thus, alternative routes of administration that bypass the liver before primary target organs are hit have been developed. Transdermal and transvaginal routes are not subject to the initial liver passage.

A more profound alteration is ethinylestradiol, the most common estrogen ingredient in combined oral contraceptive pills

Therapy

Hormone replacement therapy

If severe side-effects of low levels of estradiol in a woman's blood are experienced (commonly at the beginning of menopause or after oophorectomy), hormone replacement therapy may be prescribed. Often such therapy is combined with a progestin.

Estrogen therapy may be used in treatment of infertility in women when there is a need to develop sperm-friendly cervical mucus or an appropriate uterine lining. This is often prescribed in combination with Clomid.

Estrogen therapy can also be used in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer as well as relieving symptoms of breast cancer. [13][14]

Estrogen therapy is also used to maintain female hormone levels in male-to-female transsexuals.

Blocking estrogens

Inducing a state of hypoestrogenism may be beneficial in certain situations where estrogens are contributing to unwanted effects, e.g., certain forms of breast cancer, gynecomastia, and premature closure of epiphyses. Estrogen levels can be reduced by inhibiting production using gonadotropin- releasing factor agonists (GnRH agonists) or blocking the aromatase enzyme using an aromatase inhibitor, or estrogen effects can be reduced with estrogen antagonists such as tamoxifen. Flaxseed is known to reduce estradiol.[15]

Hormonal contraception

A derivative form of estradiol, called ethinylestradiol is a major component of hormonal contraceptive devices. Combined forms of hormonal contraception contain ethinylestradiol and a progestin, which both contribute to the inhibition of GnRH, LH, and FSH. The inhibition of these hormones accounts for the ability of these birth control methods to prevent ovulation and thus prevent pregnancy. Other types of hormonal birth control contain only progestins and no ethinylestradiol.

List of estradiol medications

Products

- Oral versions: Estrace, Estradiol acetate, Estradiol valerate, Estrofem

- Transdermal preparation: Alora, Climara, Vivelle-Dot, Menostar, Estraderm TTS, Estraderm MX, EvaMist

- Ointments: Divigel, Estrasorb Topical, Estrogel, Elestrin

- Injection: Estradiol cypionate, Estradiol valerate

- Vaginal ointment: Estrace Vaginal Cream

- Vaginal ring: Estring (estradiol acetate), Femring

- Estradiol combined with a progestin: Activella, AngeliQ, Cyclo-Progynova

Notes

Not all products are available worldwide. Estradiol is also part of conjugated estrogen preparations such as Premarin, though it is not the major ingredient (Premarin consists of hundreds of estrogen derivatives. As the name indicates, it comes from the urine of pregnant mares.)

Adverse effects

Adverse effects which may occur as a result of use of estradiol and have been associated with estrogen and/or progestin therapy include changes in vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea, increase in size of uterine leiomyomata, vaginitis including vaginal candidiasis, changes in cervical secretion and cervical ectropion, ovarian cancer; endometrial hyperplasia; endometrial cancer, nipple discharge, galactorrhea; fibrocystic breast changes and breast cancer. Cardiovascular effects include chest pain, deep and superficial venous thrombosis; pulmonary embolism; thrombophlebitis; myocardial infarction; stroke; increase in blood pressure. Gastrointestinal effects include nausea and vomiting, abdominal cramps, bloating, diarrhea, dyspepsia, dysuria, gastritis, cholestatic jaundice, increased incidence of gallbladder disease, pancreatitis, enlargement of hepatic hemangiomas. Skin adverse effects include, chloasma or melasma that may continue despite discontinuation of the drug. Other effects on the skin include erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, otitis media, hemorrhagic eruption, loss of scalp hair, hirsutism, pruritus, rash. Adverse effects on the eyes include retinal vascular thrombosis, steepening of corneal curvature, intolerance to contact lenses. Adverse central nervous system effects include headache, migraine, dizziness, mental depression, chorea, nervousness/anxiety, mood disturbances, irritability, and worsening of epilepsy. Other adverse effects include changes in weight, reduced carbohydrate tolerance, worsening of porphyria, edema, arthralgias, bronchitis, leg cramps, hemorrhoids, changes in libido, urticaria, angioedema, anaphylactic reactions, syncope, toothache, tooth disorder, urinary incontinence, hypocalcemia, exacerbation of asthma, increased triglycerides.[16][17]

Estrogen combined with medroxyprogesterone is associated with an increased risk of dementia. It is not known whether estradiol taken alone is associated with an increased risk of dementia. Estrogens should only be used for the shortest possible time and at the lowest effective dose due to these risks. Attempts to gradually reduce the medication via a dose taper should be made every 3 – 6 months.[16]

Interactions

St. John’s Wort, phenobarbital, carbamazepine and rifampin decrease the levels of estrogens such as estradiol by speeding up its metabolism whereas erythromycin, clarithromycin, ketoconazole, itraconazole, ritonavir and grapefruit juice may slow down metabolism leading to increased levels in the blood plasma.[16]

Contraindications

Estradiol should be avoided when there is undiagnosed abnormal genital bleeding, known, suspected or a history of breast cancer, current treatment for metastatic disease, known or suspected estrogen-dependent neoplasia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or history of these conditions, active or recent arterial thromboembolic disease such as stroke, myocardial infarction, liver dysfunction or disease. Estradiol should not be taken by people with a hypersensitivity/allergy or those who are pregnant or are suspected pregnancy.[16]

In the media

Scientists have identified the Marilyn Monroe hormone that is linked to an hour-glass body shape in women, and also an increased desire to trade-up to new men. Women who have high levels of oestradiol (estradiol) also show elevated confidence and a greater inclination to have sex outside of their current relationship, according to the US-based research. The ovarian steroid hormone is also associated with having a symmetrical face, large breasts, and a low waist-to-hip ratio. "Marilyn Monroe is actually a really good example of a woman who was almost certainly high in oestradiol," Australian sexologist Dr Frances Quirk said in response to the research. "She was a classic hour-glass figure and because of her relationship pattern - she was a serial monogamist. "Her relationships last three or four years or slightly longer, and, if you look at the men she had relationships with, they increased in status."

The University of Texas study took in 52 young women, aged 17 to 30, and checked their oestradiol levels using a saliva swab. They were asked to rate themselves on perceived desirability, were quizzed on their sexual motivations, and also their inclinations relating to their current relationship. An independent group also assessed photographs of the women to provide an external assessment of their attractiveness. "High-oestradiol women were considered significantly more physically attractive by themselves and others," the study, published in the journal Biology Letters, concluded. "These women reported somewhat lower levels of satisfaction with and commitment to their primary partners, and a significantly greater likelihood ... of becoming acquainted with new potential mates." The study found that, while women with high levels of oestradiol reported being "significantly more likely" to have a serious affair, they did not indicate a greater likelihood of having "brief sexual encounters." They favour long-term relationships but are "not easily satisfied by their long-term partners and are especially motivated to become acquainted with other, presumably more desirable, men." Dr. Quirk, Associate Professor at James Cook University, said that, because of these traits, high-oestradiol women "may also be the sort of women that other women don't like too much".[18]

See also

- Estrogen insensitivity syndrome

- Gender

- Androgen

- Oral contraceptive formulations

- Phytoestrogens, the family of plant chemicals which can act on estradiol receptive tissue in mammals, although the exact mechanism at hand is unclear.

References

- ↑ Wu CH, Motohashi T, Abdel-Rahman HA, Flickinger GL, Mikhail G (August 1976). "Free and protein-bound plasma estradiol-17 beta during the menstrual cycle". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 43 (2): 436–45. doi:10.1210/jcem-43-2-436. PMID 950372.

- ↑ Pentikäinen V, Erkkilä K, Suomalainen L, Parvinen M, Dunkel L. Estradiol Acts as a Germ Cell Survival Factor in the Human Testis in vitro. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2006;85:2057-67 PMID 10843196

- ↑ Sharpe RM, Skakkebaek NE. Are oestrogens involved in falling sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract? Lancet. 1993 May 29;341(8857):1392-5. PMID 8098802

- ↑ Raman JD, Schlegel PN. Aromatase Inhibitors for Male Infertility. Journal of Urology. (2002), 167: 624-629. PMID 11792932

- ↑ Carani C, Qin K, Simoni M, Faustini-Fustini M, Serpente S, Boyd J, Korach KS, Simpson ER. Effect of Testosterone and Estradiol in a Man with Aromatase Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine Volume 337:91-95 July 10, 1997 PMID 9211678

- ↑ Behl C, Widmann M, Trapp T, Holsboer F (November 1995). "17-beta estradiol protects neurons from oxidative stress-induced cell death in vitro". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 216 (2): 473–82. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.2647. PMID 7488136.

- ↑ Douma SL, Husband C, O'Donnell ME, Barwin BN, Woodend AK (2005). "Estrogen-related mood disorders: reproductive life cycle factors". ANS Adv Nurs Sci 28 (4): 364–75. PMID 16292022.

- ↑ Lasiuk GC, Hegadoren KM (October 2007). "The effects of estradiol on central serotonergic systems and its relationship to mood in women". Biol Res Nurs 9 (2): 147–60. doi:10.1177/1099800407305600. PMID 17909167.

- ↑ Collins P, Rosano GM, Sarrel PM, Ulrich L, Adamopoulos S, Beale CM, McNeill JG, Poole-Wilson PA. 17 beta-Estradiol attenuates acetylcholine-induced coronary arterial constriction in women but not men with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1995 Jul 1;92(1):24-30 PMID 7788912

- ↑ Harding, Prof. Cheryl F. (June 2004). "Hormonal Modulation of Singing: Hormonal Modulation of the Songbird Brain and Singing Behavior". Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. (The New York Academy of Sciences) 1016: 524–539. doi:10.1196/annals.1298.030. PMID 15313793. http://www.annalsnyas.org/content/vol1016/issue1/index.dtl. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ↑ Simerly, Richard B. (2002-03-27). "Wired for reproduction: organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain" (pdf). Annual Rev. Neurosci. 25: 507–536. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142745. PMID 12052919. http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/neuroscience/BehavioralNeuroscience/Simerley-EFR-1-4.pdf. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ↑ Hulshoff, Cohen-Kettenis et al. (July 2006). "Changing your sex changes your brain: influences of testosterone and estrogen on adult human brain structure". European Journal of Endocrinology 155 (155): 107–114. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02248. ISSN 0804-4643. http://www.eje-online.org/cgi/content/abstract/155/suppl_1/S107.

- ↑ Ockrim JL, Lalani el-N, Kakkar AK, Abel PD (August 2005). "Transdermal estradiol therapy for prostate cancer reduces thrombophilic activation and protects against thromboembolism.". PubMed. National Institute of Health. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16006886. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ↑ Giuseppe Carruba, Ulrich Pfeffer, Emanuela Fecarotta, Domenico A. Coviello, Elena D'Amato, Michele Lo Casto, Giorgio Vidali, and Luigi Castagnetta (September 7, 1993). "Estradiol Inhibits Growth of Hormone-nonresponsive PC3 Human Prostate Cancer Cells". Cancer Research. American Association for Cancer Research, Inc. (AACR). http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/54/5/1190.abstract. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ↑ Chevallier, Andrew (2000). Gillian Emerson-Roberts. ed. Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine: The Definitive Home Reference Guide to 550 Key Herbs with all their Uses as Remedies for Common Ailments. DK Publishing. ISBN 0-7894-6783-6.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Barr Laboratories, Inc. (March 2008). "ESTRACE® TABLETS, (estradiol tablets, USP)" (PDF). wcrx.com. http://www.wcrx.com/pdfs/pi/pi_estrace_wc_imprint.pdf. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ↑ Pfizer (August 2008). "ESTRING® (estradiol vaginal ring)" (PDF). http://media.pfizer.com/files/products/uspi_estring.pdf.

- ↑ Danny Rose (January 14, 2009). "Marilyn Monroe' hormone discovered". AAP. http://www.news.com.au/story/0,27574,24913504-23109,00.html.

Additional images

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||