Haloperidol

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

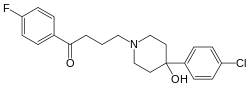

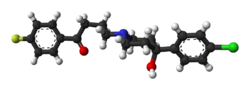

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 4-[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxy-1-piperidyl]-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-butan-1-one | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 52-86-8 |

| ATC code | N05AD01 |

| PubChem | CID 3559 |

| IUPHAR ligand | 86 |

| DrugBank | DB00502 |

| ChemSpider | 3438 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C21H23ClFNO2 |

| Mol. mass | 375.9 g/mol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Approx. 60 to 70% (tablets and liquid) |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Half-life | 12 to 36 hours |

| Excretion | Biliary and renal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | C |

| Legal status | ℞ Prescription only |

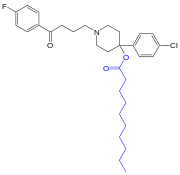

| Routes | Oral, IM, IV, depot (as decanoate ester) |

| |

|

Haloperidol is a typical antipsychotic. It is in the butyrophenone class of antipsychotic medications and has pharmacological effects similar to the phenothiazines.

Haloperidol is an older antipsychotic used in the treatment of schizophrenia and, more acutely, in the treatment of acute psychotic states and delirium. A long-acting decanoate ester is used as a long acting injection given every 4 weeks to people with schizophrenia or related illnesses who have a poor compliance with medication and suffer frequent relapses of illness, or to overcome the drawbacks inherent to its orally administered counterpart that burst dosage increases risk or intensity of side effects. In some countries this can be involuntary under Community Treatment Orders.

Haloperidol is sold under the tradenames Aloperidin, Bioperidolo, Brotopon, Dozic, Duraperidol (Germany), Einalon S, Eukystol, Haldol, Halosten, Keselan, Linton, Peluces, Serenace, Serenase, and Sigaperidol.

Contents |

History

Haloperidol was discovered by Paul Janssen.[1] It was developed in 1958 by the Belgian company Janssen Pharmaceutica and submitted to first clinical trials in Belgium in the same year.[2] After being rejected by U.S. company Searle due to side effects, it was later marketed in the U.S. by McNeil Laboratories. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on April 12, 1967.

Pharmacology

Haloperidol is an antipsychotic and butyrophenone. Due to its strong central antidopaminergic action, it is classified as a highly potent neuroleptic. It is approximately 50 times more potent than chlorpromazine (sold under the brand name Thorazine, among others) on a weight basis (50 mg chlorpromazine is equivalent to 1 mg haloperidol). Haloperidol possesses a strong activity against delusions and hallucinations, most likely due to an effective dopaminergic receptor blockage in the mesocortex and the limbic system of the brain. It blocks the dopaminergic action in the nigrostriatal pathways, which is the probable reason for the high frequency of extrapyramidal-motoric side effects (dystonias, akathisia, pseudoparkinsonism). It has minor antihistaminic and anticholinergic properties, therefore cardiovascular and anticholinergic side effects such as hypotension, dry mouth, constipation, etc., are seen quite infrequently, compared with less potent neuroleptics such as chlorpromazine. Haloperidol also has sedative properties and displays a strong action against psychomotor agitation due to a specific action in the limbic system. However, in some cases haloperidol may worsen psychomotor agitation via its potent dopamine receptor antagonism. Dopamine receptor antagonism, notably of the D2 receptor subtype, can cause akathisia, psychomotor agitation, anxiety, and restlessness, which may worsen the condition of some patients.

The peripheral antidopaminergic effects of haloperidol account for its strong antiemetic activity. There, it acts at the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ). Haloperidol is useful to treat severe forms of nausea/emesis such as those resulting from chemotherapy. The peripheral effects lead also to a relaxation of the gastric sphincter muscle and an increased release of the hormone prolactin, with the possible emergence of breast enlargement and secretion of milk (galactorrhea) in both sexes.

Pharmacokinetics

Intramuscular injections

The drug is well and rapidly absorbed and has a high bioavailability. Plasma-levels reach their maximum within 20 minutes after injection. The decanoate injectable formulation is for intramuscular administration only and should never be used intravenously.

Intravenous injections

The bioavailability is 100% and the very rapid onset of action is seen within seconds. The duration of action is 3 to 6 hours. If haloperidol is given as a slow IV infusion, the onset of action is slowed, and the duration prolonged.

Therapeutic concentrations

Plasma levels of 4 to 25 micrograms per liter are required for therapeutic action. The determination of plasma levels can be used to calculate dose adjustments and to check compliance, particularly in long-term patients. Plasma levels in excess of the therapeutic range may lead to a higher incidence of side effects or even pose the risk of haloperidol intoxication.

Uses

A comprehensive review of haloperidol has found it to be an effective agent in treatment of symptoms associated with schizophrenia.[3] Haloperidol is also used in the control of the symptoms of:

- Acute psychosis, such as drug psychosis (LSD, psilocybin, amphetamines, ketamine,[4] and phencyclidine[5]), psychosis associated with high fever or metabolic disease

- Acute manic phases until the concomitantly given first-line drugs such as lithium or valproate are effective

- Hyperactivity, aggression.

- Acute delirium

- Otherwise uncontrollable severe behavioral disorders in children and adolescents

- Agitation and confusion associated with cerebral sclerosis

- Adjunctive treatment of alcohol and opioid withdrawal

- Treatment of neurological disorders such as tic disorders, Tourette syndrome, and chorea

- Treatment of severe nausea/emesis (postoperative, side effects of radiation and cancer chemotherapy)

- Adjunctive treatment of severe chronic pain, always together with analgesics

- Therapeutic trial in personality disorders such as borderline personality disorder

- Also used in the treatment of intractable hiccups

In Aquaculture

- Also used to block dopamine receptor to enable GnrHA function for ovulation use in spawning fish.

Some weeks or even months of treatment may be needed before a remission of schizophrenia is evident.

In some clinics the use of atypical neuroleptics (e.g. clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, ziprasidone) is generally preferred over haloperidol, because these drugs have an appreciably lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects. Each of these drugs, however, has its own spectrum of potentially serious side effects (e.g. agranulocytosis with clozapine, weight gain with increased risk of diabetes and of stroke). Atypical neuroleptics are also much more expensive and have recently been the subject of increasing controversy regarding their efficacy in comparison to older products and side effects.

Haloperidol was considered indispensable for treating psychiatric emergency situations,[6][7] although the newer atypical drugs have gained greater role in a number of situations as outlined in a series of consensus reviews published between 2001 and 2005.[3][8][9][10] It is enrolled in the World Health Organization List of Essential Medicines.

As is common with typical neuroleptics, haloperidol is by far more active against "positive" psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations etc.) than against "negative" symptoms (social withdrawal, autism etc.). With the exception of the highly effective clozapine, the effectiveness of haloperidol against positive symptoms has not been outperformed by newer antipsychotics.

A multi-year UK study by the Alzheimer's Research Trust suggested that this and other neuroleptic anti-psychotic drugs commonly given to Alzheimer's patients with mild behavioural problems often make their condition worse.[11] The study concluded that

| “ | For most patients with AD, withdrawal of neuroleptics had no overall detrimental effect on functional and cognitive status and by some measures improved functional and cognitive status. Neuroleptics may have some value in the maintenance treatment of more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms, but this possibility must be weighed against the unwanted effects of therapy. The current study helps to inform a clinical management strategy for current practice, but the considerable risks of maintenance therapy highlight the urgency of further work to find, develop, and implement safer and more effective treatment approaches for neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with AD. | ” |

Controversial non-medical uses

There are multiple reports from Soviet dissidents, including medical staff, on the use of haloperidol in the Soviet Union for punitive purposes or simply to break the prisoners' will.[12][13][14] Notable dissidents that were administered haloperidol as part of their court ordered treatment were Sergei Kovalev and Leonid Plyushch.[15] The accounts of Plyushch in the West, after he was allowed to leave the Soviet Union in 1976, were instrumental in the triggering Western condemnation of Soviet practices at the World Psychiatric Association's 1977 meeting.[16] The use of haloperidol in the Soviet Union's psychiatric system was prevalent because it was one of the few psychotropic drugs produced in quantity in the USSR.[17]

Haloperidol has been used for its sedating effects during the deportations of immigrants by the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). During 2002-2008, federal immigration personnel used haloperidol to sedate 356 deportees. By 2008, following court challenges over the practice, haloperidol was given to only 3 detainees. Following lawsuits, U.S. officials changed the procedure so that it is done only by the recommendation of medical personnel and under court order.[18][19]

Contraindications

Absolute

- Preexisting coma, acute stroke

- Severe intoxication with alcohol or other central depressant drugs

- Known allergy against haloperidol or other butyrophenones or other drug ingredients

- Known heart disease; when combined will tend towards cardiac arrest

Special caution needed

- Preexisting Parkinson's disease[20]

- Patients at special risk for the development of QT prolongation (hypokalemia, concomitant use of other drugs causing QT prolongation)

- Compromised liver-function (as haloperidol is metabolized and eliminated mainly by the liver, dose reductions and/or spaced intervals may be needed)

- Haloperidol may decrease the seizure-threshold. Treat patients with epilepsy and those with risk factors for the development of seizures (alcohol withdrawal, encephalopathy) with caution. Maintain existing anticonvulsive therapy.

- Patients with hyperthyreosis; the action of haloperidol is intensified and side effects are more likely. Initiate an effective therapy of hyperthyreosis.

- IV injections: inject slowly to avoid hypotension or orthostatic collapse. Avoid IV injections in cardiovascular unstable patients (preexisting hypotension, shock, concomitant antihypertensive therapy, heart insufficiency). Prefer in these cases moderate oral or IM doses.

Adverse effects

The drug is noted for its strong early and late extrapyramidal side effects.[3] The risk of the facial disfiguring tardive dyskinesia is around 4% per year in younger patients. Other predispositive factors may be female gender, preexisting affective disorder and cerebral dysfunction.

Akathisia manifests itself with anxiety, dysphoria, and an inability to remain motionless.

Other side effects include dry mouth, lethargy, restlessness of akathisia, muscle-stiffness, muscle-cramping, restlessness, tremors, Rabbit syndrome and weight-gain; side effects like these are more likely to occur when the drug is given in high doses and/or during long-term treatment. Depression, severe enough to result in suicide, is quite often seen during long-term treatment. Care should be taken to detect and treat depression early in course. Sometimes the change from haloperidol to a mildly potent neuroleptic (e.g. chlorprothixene or chlorpromazine), together with appropriate antidepressant therapy, does help. Sedative and anticholinergic side effects occur more frequently in the elderly. The likelihood of experiencing one or more of these side effects is quite high regardless of age and gender, especially with prolonged use.

Symptoms of dystonia, prolonged abnormal contractions of muscle groups, may occur in susceptible individuals during the first few days of treatment. Dystonic symptoms include: spasm of the neck muscles, sometimes progressing to tightness of the throat, swallowing difficulty, difficulty breathing, and/or protrusion of the tongue. While these symptoms can occur at low doses, they occur more frequently and with greater severity with high potency and at higher doses of first generation antipsychotic drugs. An elevated risk of acute dystonia is observed in males and younger age groups.

The potentially fatal neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a significant possible side effect. Haloperidol and fluphenazine are the two drugs which cause NMS most often. NMS involves fever and other symptoms. Allergic and toxic side effects occur. Skin rash and photosensitivity both occur in less than 1% of patients.

Children and adolescents are particularly sensitive to the early and late extrapyramidal side effects of haloperidol. It is not recommended to treat pediatric patients: use is only indicated if the psychiatric or neurologic disorder is so substantial as to be completely intractable by all other means.

QT prolongation with sudden death is a rarely seen but clinically significant side effect. Likewise, the development of thromboembolic complications are also seen.

Haloperidol may have a negative impact on vigilance or decrease the ability of the patient to drive or operate a machine, particularly initially.

Haloperidol is not devoid of potential psychological dependence. However, due to the debilitating side effects, patients prescribed this drug have a high rate of non-compliance. The current recommendation is to pay close attention to the patient's experience, and taper or discontinue use if the patient has a high rate of dissatisfaction with treatment as it may lead to dangerously rapid discontinuation.

Unpleasant withdrawal symptoms, if haloperidol is stopped abruptly after long-term treatment, are often noted. These are usually agitation, anxiety, insomnia, and nausea. Rebound of psychotic symptoms and mood swing into mania are also seen. Long-standing, though not not usually permanent cognitive difficulties can result, although objective evaluation of this is difficult due to concomitant medication and disability. However, studies show that long term use of antipsychotics like Holoperidol often causes large brain lesions, and therefore complicates any potential recovery. It is considered by some psychiatrist, especially in Europe, to be overprescribed and very detrimental to the functional recovery of those afflicted by schizophrenia. Use in milder conditions is not indicated.

Haloperidol has been shown to dramatically increase dopamine activity, up to 98%, in test subjects after two weeks on a "moderate to high" dose compared to chronic schizophrenics.[21] In another study, a live survey of a patient showed that the person has 90% more dopamine receptors, of the D2 subtype, than before treatment with haloperidol.[21] The long term effect of this is unknown, but the first study concludes that this upregulation is positively associated with severe dyskinesias.(more upregulation, more dyskinesia)

In a placebo-compared study of six macaques receiving haloperidol for up to 27 months, a significant brain volume and weight decreases were detected.[22] In latter studies of the stored samples, the changes were attributed to astrocyte and oligodendrocyte loss.[23] The neuron loss was 5%, but this was not statistically significant. Normally this is described as the "neurons was spared but positioned more closely compared to the controls", but this is not true.

Other remarks

During long-term treatment of chronic psychiatric disorders, it should be tried - in regular intervals - to reduce the daily dose to the lowest level needed for maintenance of remission. Sometimes, it may be indicated to terminate haloperidol treatment gradually.

Other forms of therapy (psychotherapy, occupational therapy/ergotherapie, social rehabilitation) should be instituted properly.

Pregnancy and lactation

Data from animal experiments indicate haloperidol is not teratogenic, but is embryotoxic in high doses. In humans, no controlled studies exist. Unconfirmed studies in pregnant women revealed possible damage to the fetus, although most of the women were exposed to multiple drugs during pregnancy. Following accepted general principles, haloperidol should only be given during pregnancy if the benefit to the mother clearly outweighs the potential fetal risk.

Haloperidol, when given to lactating women, is found in significant amounts in their milk. Breastfed children sometimes show extrapyramidal symptoms. If the use of haloperidol during lactation seems indicated, the benefit for the mother should clearly outweigh the risk for the child. Consider termination of breastfeeding.

Carcinogenicity

So far, no statistically acceptable evidence is found to associate long-term use of haloperidol with the potential for increased breast cancer risk in female patients. In an unconfirmed study at the Buffalo Psychiatric Center, relative risks of breast cancer in inmates undergoing long-term treatment with haloperidol were 3.5 times higher than that of patients at the general hospital, and 9.5 times higher than the reported incidents in the general population.[24] These results need confirmation by larger studies.

Interactions

- Other central depressants (alcohol, tranquilizers, narcotics): actions and side effects of these drugs (sedation, respiratory depression) are increased. In particular, the doses of concomitantly used opioids for chronic pain can be reduced by 50%.

- Methyldopa: increased risk of extrapyramidal side effects and other unwanted central effects

- Levodopa: decreased action of levodopa

- Tricyclic antidepressants: metabolism and elimination of tricyclics significantly decreased, increased toxicity noted (anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects, lowering of seizure-threshold)

- Quinidine, buspirone, and fluoxetine: increased plasma-levels of haloperidol, decrease haloperidol dose, if necessary

- Carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and rifampicin: plasma-levels of haloperidol significantly decreased, increase haloperidol dose, if necessary.

- lithium: rare cases of the following symptoms have been noted: encephalopathy, early and late extrapyramidal side effects, other neurologic symptoms and coma. Check lithium plasma levels regularly and keep the dose of haloperidol as low as possible.

- Guanethidine: antihypertensive action antagonized

- Epinephrine: action antagonized, paradoxical decrease in blood pressure may result

Doses

As directed by the physician, depends on the condition to be treated, age and weight of patient:

- Acute problems: single doses of 1 mg to 5 mg (up to 10 mg) oral or i.m., usually repeated every 4 to 8 hours. Do not exceed an oral dose of 100 mg daily. Doses used for IV injection are usually 5 to 10 mg as a single dose; not exceeding 50 mg daily.

- Chronic conditions: 0.5 to 20 mg daily oral, rarely more. The lowest dose that maintains remission should be employed.

- Experimental doses: In resistant cases of psychosis small studies with oral doses of up to 300 mg - 500 mg daily have been conducted (in most cases together with an anticholinergic antiparkinsonian drug (Biperiden, Benztropine, etc.) to avoid severe early extrapyramidal side effects. These studies showed no superior results and led to severe side effects. Also, the frequency of otherwise unusual side effects (hypotension, QT-time prolongation, and serious cardiac arrhythmias) was dramatically increased. The clinical use of haloperidol in these doses is discouraged now and it is recommended to switch the patient gradually to a different neuroleptic (e.g. clozapine, olanzapine, aripiprazole).

Depot forms are also available; these are injected deeply i.m. at regular intervals. The depot forms are not suitable for initial treatment

Overdose

Experimental evidence from animal studies indicates that doses needed for acute poisoning are quite high in relation to therapeutic doses.

Overdoses with depot injections are uncommon, because only certified personnel are legally permitted to administer them to patients.

Symptoms

Symptoms are usually due to exaggerated side effects. Most often encountered are:

- Severe extrapyramidal side effects with muscle rigidity and tremors, akathisia etc. (inject 5 mg biperiden (Akineton) slowly IV, repeat after some hours if necessary). Sometimes oral or IM treatment with biperiden is needed for several days or even weeks. If the patient is very upset about extrapyramidal side effects, small doses of lorazepam (0.5 to 1 mg orally, repeated every 4 to 6 hours if necessary) can be given. Lorazepam has an intrinsic action against upset, anxiety, and extrapyramidal side effects.

- Hypotension or hypertension

- Sedation

- Anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, constipation, paralytic ileus, difficulties in urinating, massive sweating). Cautious doses of physostigmine may be given repeatedly. Physostigmine may increase the risk of seizures.

- Coma in severe cases, accompanied by respiratory depression and massive hypotension, shock

- Rarely serious ventricular arrhythmia (torsades de pointes) with or without prolonged QT-time

- Epileptic seizures, give careful doses of diazepam 5 mg to 10 mg by slow IV injection, repeatedly if needed, until seizures subside. Take care not to worsen central depression or respiratory depression caused by haloperidol. The treatment facility should be able to institute artificial respiration readily. Valproate first given as slow IV infusion and later orally may also be effective.

Treatment

Treatment is merely symptomatic and involves intensive care with stabilization of vital functions. In early detected cases of oral overdose induction of emesis, gastric lavage and the use of activated charcoal can all be tried. Avoid epinephrine for treatment of hypotension and shock, because its action might be reversed.

Prognosis

Generally, the prognosis of overdose is good and lasting damage is not known, provided that the patient has survived the initial phase.

Other formulations

The decanoate ester of haloperidol (Haloperidol decanoate, trade names Haldol decanoate, Halomonth, Neoperidole) has a much longer duration of action, and therefore is often used in people known to be noncompliant with oral medication. A dose of 25 to 250 mg is given by intramuscular injection once every two to four weeks.[25]

The IUPAC name of haloperidol decanoate is 4-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-1[4-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxobutyl]-4 piperidinyl decanoate.

Veterinary use

Haloperidol is also used on many different kinds of animals. It appears to be particularly successful when given to birds; e.g. a parrot that will otherwise continuously pluck its feathers out.

Dose forms

- Liquid: 2 mg/mL, also 10 mg/mL

- Tablets: 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg

- Injection: 5 mg (1 mL)

- Depot injection forms

- The original brand Haldol and many generics are available

See also

- Biological psychiatry

References

- ↑ Healy, David (1996). The psychopharmacologists. 1. London: Chapman and Hall. ISBN 978-1-86036-008-4.

- ↑ Granger B, Albu S (2005). "The haloperidol story". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists 17 (3): 137–40. doi:10.1080/10401230591002048. PMID 16433054.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Joy CB, Adams CE, Lawrie SM (2006). "Haloperidol versus placebo for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003082. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003082.pub2. PMID 17054159. http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003082/frame.html.

- ↑ Giannini AJ, Underwood NA, Condon M (November 2000). "Acute ketamine intoxication treated by haloperidol: a preliminary study". American Journal of Therapeutics 7 (6): 389–92. doi:10.1097/00045391-200007060-00008. PMID 11304647.

- ↑ Giannini AJ, Eighan MS, Loiselle RH, Giannini MC (April 1984). "Comparison of haloperidol and chlorpromazine in the treatment of phencyclidine psychosis". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 24 (4): 202–4. doi:10.3109/15563658408992586. PMID 6725621.

- ↑ Cavanaugh SV (1986). "Psychiatric emergencies". Med. Clin. North Am. 70 (5): 1185–202. PMID 3736271.

- ↑ Currier GW (2003). "The controversy over "chemical restraint" in acute care psychiatry". J Psychiatr Pract 9 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00006. PMID 15985915.

- ↑ Allen MH, Currier GW, Hughes DH, Reyes-Harde M, Docherty JP (2001). "The Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Treatment of behavioral emergencies". Postgrad Med (Spec No): 1–88; quiz 89–90. PMID 11500996.

- ↑ Allen MH, Currier GW, Hughes DH, Docherty JP, Carpenter D, Ross R (2003). "Treatment of behavioral emergencies: a summary of the expert consensus guidelines". J Psychiatr Pract 9 (1): 16–38. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00004. PMID 15985913.

- ↑ Allen MH, Currier GW, Carpenter D, Ross RW, Docherty JP (2005). "The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of behavioral emergencies 2005". J Psychiatr Pract 11 Suppl 1: 5–108; quiz 110–2. doi:10.1097/00131746-200511001-00002. PMID 16319571.

- ↑ Ballard C, Lana MM, Theodoulou M, et al. (April 2008). "A randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled trial in dementia patients continuing or stopping neuroleptics (the DART-AD trial)". PLoS Medicine 5 (4): e76. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050076. PMID 18384230. Lay summary – BBC News (2008-04-01). "Neuroleptics provided no benefit for patients with mild behavioural problems, but were associated with a marked deterioration in verbal skills".

- ↑ Podrabinek, Aleksandr (1980). Punitive Medicine. Ann Arbor Mich.: Karoma Publishers. pp. 15–20. ISBN 0897200225.

- ↑ Kosserev I, Crawshaw R (1994). "Medicine and the Gulag". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 309 (6970): 1726–30. PMID 7820004.

- ↑ de Boer, S. P.; E. J. Driessen, H. L. Verhaar (1982). Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in the Soviet Union, 1956-1975. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9024725380.

- ↑ Wade N (November 1976). "Sergei Kovalev: Biologist Denied Due Process and Medical Care". Science (New York, N.Y.) 194 (4265): 585–587. doi:10.1126/science.194.4265.585. PMID 17818411.

- ↑ "Censuring the Soviets". TIME (CNN). 1977-09-12. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,915433,00.html. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ The Children of Pavlov, TIME, Jun. 23, 1980

- ↑ "Fewer US deportees being sedated for removal". Associated Press. Epilepsy.com. 2008-12-30. http://www.epilepsy.com/newsfeeds/view/5974. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ Solis, Dianne (2009-01-05). "U.S. cuts back on sedating deportees with Haldol". Seattle Times. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/nationworld/2008590327_deport05.html. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ Leentjens AF, van der Mast RC (May 2005). "Delirium in elderly people: an update". Current Opinion in Psychiatry 18 (3): 325–30. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165603.36671.97. PMID 16639157. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/503089_6. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Silvestri S, Seeman MV, Negrete JC, et al. (October 2000). "Increased dopamine D2 receptor binding after long-term treatment with antipsychotics in humans: a clinical PET study". Psychopharmacology 152 (2): 174–80. doi:10.1007/s002130000532. PMID 11057521.

- ↑ Dorph-Petersen KA, Pierri JN, Perel JM, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Lewis DA (September 2005). "The influence of chronic exposure to antipsychotic medications on brain size before and after tissue fixation: a comparison of haloperidol and olanzapine in macaque monkeys". Neuropsychopharmacology 30 (9): 1649–61. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300710. PMID 15756305.

- ↑ Konopaske GT, Dorph-Petersen KA, Sweet RA, Pierri JN, Zhang W, Sampson AR, Lewis DA (April 2008). "Effect of chronic antipsychotic exposure on astrocyte and oligodendrocyte numbers in macaque monkeys". Biol. Psychiatry 63 (8): 759–65. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.018. PMID 17945195.

- ↑ Halbreich U, Shen J, Panaro V (1996). "Are chronic psychiatric patients at increased risk for developing breast cancer?". Am J Psychiatry 153 (4): 559–60. PMID 8599407. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=8599407.

- ↑ Goodman and Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 10th edition (McGraw-Hill, 2001).

Haloperidol Gel for topical use. Such as 0.5 mg/1ml/pack-give every 2 hours only as needed.

External links

- Rx-List.com - Haloperidol

- Medline plus - Haloperidol

- Swiss scientific information on Haldol

- "WHO List of Essential Drugs". Archived from the original on 2007-12-29. http://web.archive.org/web/20071229074233/http://mednet3.who.int/EMLib/DiseaseTreatments/MedicineDetails.aspx?MedIDName=156@haloperidol.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Haloperidol

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||