Mescaline

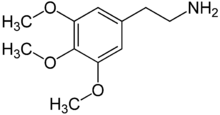

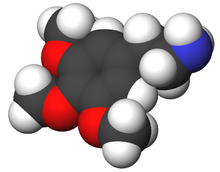

Mescaline or 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine is a naturally-occurring psychedelic alkaloid of the phenethylamine class used mainly as an entheogen.

It occurs naturally in the peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii),[1] the San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi) and the Peruvian Torch cactus (Echinopsis peruviana), and in a number of other members of the Cactaceae plant family. It is also found in small amounts in certain members of the Fabaceae (bean) family, including Acacia berlandieri.[2] Mescaline was first isolated and identified in 1897 by the German Arthur Heffter and first synthesized in 1919 by Ernst Späth.

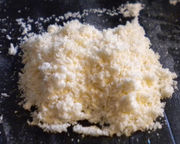

Naturally derived mescaline powder extract.

History and usage

Peyote has been used for over 3000 years by Native Americans in Mexico.[1] Europeans noted use of peyote in Native American religious ceremonies upon early contact, notably by the Huichols in Mexico. Other mescaline-containing cacti such as the San Pedro have a long history of use in South America, from Peru to Ecuador.

In traditional peyote preparations the top of the cactus is cut at ground level, leaving the large tap roots to grow new 'Heads'. These 'Heads' are then dried to make disk-shaped buttons. Buttons are chewed to produce the effects or soaked in water for an intoxicating drink. However, the taste of the cactus is bitter, so users will often grind it into a powder and pour it in capsules to avoid having to taste it. The usual human dosage is 200–400 milligrams of mescaline sulfate or 178–356 milligrams of mescaline hydrochloride.[3] The average 3 inch button contains about 25 mg mescaline.[4]

Aldous Huxley described his experience with mescaline in The Doors of Perception. Aleister Crowley reported using mescaline in his diary. The sex psychologist Havelock Ellis also tried mescaline. Mescaline may have played a part in the development of the Cubist school of abstract art, when George Braque and Pablo Picasso published the "Cubist Manifesto" they described design paradigms which were similar to visual experiences induced by mescaline and other rare drugs known to the South American Islanders.[5] Hunter S. Thompson recounted his use of mescaline in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Pharmacokinetics

Tolerance builds with repeated usage, lasting for a few days. Mescaline causes cross-tolerance with LSD and other psychedelics.

About half the initial dosage is excreted after 6 hours, but some studies suggest that it is not metabolized at all before excretion.

Mescaline appears to not be subject to metabolism by CYP2D6[6] and between 20 and 50% of mescaline is excreted in the urine unchanged, and the rest being excreted as the carboxylic acid form of mescaline, a likely result of MAO degradation.[7]

The LD50 of mescaline has been measured in various animals: 212 mg/kg i.p. (mice), 132 mg/kg i.p. (rats), and 328 mg/kg i.p. (guinea pigs).

Behavioral and non-behavioral effects

The visual distortions produced by mescaline are somewhat different from those of LSD. The subjective "visuals" are not true Hallucinations as they are consistent with actual experience and typically intensifications of the different stimulus (objects and sounds), not the appearance of non existent fanciful objects or actions that the user believes are real. Prominence of color is distinctive, appearing brilliant and intense. Placing a strobing light in front of closed eyelids can produce brilliant visual effects at the peak of the experience. Recurring visual patterns observed during the mescaline experience include stripes, checkerboards, angular spikes, multicolored dots, and very simple fractals which turn very complex. Aldous Huxley described these self transforming amorphous shapes as like animated stained glass illuminated from light coming through the eyelids. Like LSD, mescaline induces distortions of form and kaleidoscopic experiences but which manifest more clearly with eyes closed and under low lighting conditions; however, all of these visual descriptions are purely subjective. Research into the root causes for the patterns associated with mescaline, LSD and DMT have given rise to mathematical theories that explain the biological processes that are disrupted by molecules like mescaline.[8]

As with LSD, synesthesia can occur especially with the help of music.[9] An unusual but unique characteristic of mescaline use is the "geometricization" of three-dimensional objects. The object can appear flattened and distorted, similar to the presentation of a Cubist painting.[10]

Mescaline elicits a pattern of sympathetic arousal, with the peripheral nervous system being a major target for this drug.[9] Effects last for up to 12 hours.[9]

Mode of action

Mescaline acts similarly to other psychedelic agents.[11] It binds to and activates the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor with a high affinity as a partial agonist.[12] How activating the 5-HT2A receptor leads to psychedelia is still unknown, but it likely somehow involves excitation of neurons in the prefrontal cortex.[13]

Legality

In the US, mescaline was made illegal in 1970 by the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act.[14] It was prohibited internationally by the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances[15] and is categorized as a Schedule I hallucinogen by the CSA. Mescaline is only legal for certain religious groups (such as the Native American Church) and in scientific and medical research. In 1990, the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Oregon could bar the use of mescaline in Native American religious ceremonies. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 1993 allowed the use of peyote in religious ceremony but in 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that RFRA was unconstitutional when applied against states. However, a subsequent ruling in 2006 held that RFRA was constitutional when applied against the federal government.[16] Thus, the current state of the law is that, while the federal government may not restrict use of peyote in ceremony, individual states do have a right to restrict it.[17] Penalties for manufacture or sale can be as high as five years in prison and a fine of $15,000, with a penalty of up to one year and fine of $5000 for possession.

In the UK, mescaline is a Class A drug (in purified powder form, although dried cactus can be bought and sold legally, unlike raw "magic" mushrooms, which are now illegal),[18] and so carries the following penalties. For possession: up to seven years in prison or an unlimited fine or both. For dealing: up to life in prison or an unlimited fine or both.

In Canada, mescaline in raw form is considered an illegal drug. However, anyone may grow and use peyote, or Lophophora williamsii, without restriction, as it is specifically exempt from legislation.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Drug Identification Bible. Grand Junction, CO: Amera-Chem, Inc.. 2007. ISBN 0-9635626-9-X.

- ↑ Chemistry of Acacia's from South Texas

- ↑ http://www.erowid.org/library/books_online/pihkal/pihkal096.shtml

- ↑ AJ Giannini, AE Slaby, MC Giannini. Handbook of Overdose and Detoxification Emergencies.New Hyde Park, NY. Medical Examination Publishing/Excerpta Medica Company,1982.

- ↑ AJ Giannini. Drugs of Abuse—Second Edition. Los Angeles, Practice Management Information Corp., 1997.

- ↑ Wu D, Otton SV, Inaba T, Kalow W, Sellers EM (June 1997). "Interactions of amphetamine analogs with human liver CYP2D6". Biochem. Pharmacol. 53 (11): 1605–12. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(97)00014-2. PMID 9264312. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006-2952(97)00014-2.

- ↑ Cochin J, Woods LA, Seevers MH (February 1951). "The absorption, distribution and urinary excretion of mescaline in the dog". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 101 (2): 205–9. PMID 14814616. http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14814616.

- ↑ [1], Biological Cybernetics 1979.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Diaz, Jaime. How Drugs Influence Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1996

- ↑ AJ Giannini, AE Slaby. Drugs of Abuse. Oradell, NJ. Medical Economics Books,1989, pp.207-239.

- ↑ Nichols DE (February 2004). "Hallucinogens". Pharmacol. Ther. 101 (2): 131–81. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002. PMID 14761703.

- ↑ Monte AP, Waldman SR, Marona-Lewicka D, et al. (September 1997). "Dihydrobenzofuran analogues of hallucinogens. 4. Mescaline derivatives". J. Med. Chem. 40 (19): 2997–3008. doi:10.1021/jm970219x. PMID 9301661.

- ↑ Béïque JC, Imad M, Mladenovic L, Gingrich JA, Andrade R (June 2007). "Mechanism of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor-mediated facilitation of synaptic activity in prefrontal cortex". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (23): 9870–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700436104. PMID 17535909.

- ↑ United States Department of Justice. "Drug Scheduling". http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/scheduling.html. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ↑ "List of psychotropic substances under international control". International Narcotics Control Board. http://www.incb.org/pdf/e/list/green.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ↑ [http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgi-bin/getcase.pl?court=US&navby=case&vol=000&invol=04-1084 GONZALES, ATTORNEY GENERAL, et al. v. O CENTRO ESPIRITA BENEFICENTE UNIAO DO VEGETAL et al.]

- ↑ "Uses Drugs of Abuse—Origins and Effects - Hallucinogens". http://www.libraryindex.com/pages/2339/Drugs-Abuse-Origins-Uses-Effects-HALLUCINOGENS.html.

- ↑ "2007 U.K. Trichocereus Cacti Legal Case Regina v. Saul Sette". http://www.erowid.org/plants/cacti/cacti_law2.shtml.

External links

|

Hallucinogens |

|

Psychedelics

5-HT2AR agonists |

Lysergamides: AL-LAD • ALD-52 • BU-LAD • CYP-LAD • DAM-57 • Diallyllysergamide • Ergometrine (Ergonovine, Ergobasine) • ETH-LAD • LAE-32 • LSA (Ergine, Lysergamide) • LSD • LSH • LPD-824 • LSM-775 • Lysergic Acid 2-Butyl Amide • Lysergic Acid 2,4-Dimethylazetidide • Methylergometrine • Methylisopropyllysergamide • Methysergide • MLD-41 • PARGY-LAD • PRO-LAD;

Phenethylamines: Aleph • 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2CBFly-NBOMe • 2C-C • 2C-D • 2CD-5EtO • 2C-E • 2C-F • 2C-G • 2C-I • 2C-N • 2C-O • 2C-O-4 • 2C-P • 2C-T • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-4 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-8 • 2C-T-9 • 2C-T-13 • 2C-T-15 • 2C-T-17 • 2C-T-21 • 2C-TFM • 2C-YN • 2CBCB-NBOMe • 25B-NBOMe • 25I-NBMD • 25I-NBOH • 25I-NBOMe • 3C-E • 3C-P • Br-DFLY • DESOXY • DMMDA • DMMDA-2 • DOB • DOC • DOEF • DOET • DOF • DOI • DOM • DON • DOPR • DOTFM • Escaline • Ganesha • HOT-2 • HOT-7 • HOT-17 • IAP • Isoproscaline • Jimscaline • Lophophine • MDA • MDEA • MDMA • MMA • MMDA • MMDA-2 • MMDA-3a • MMDMA • Macromerine • Mescaline • Methallylescaline • Proscaline • TCB-2 • TFMFly • TMA;

Piperazines: pFPP • TMFPP;

Tryptamines: 1-Methyl-5-methoxy-diisopropyltryptamine • 2,N,N-TMT • 4,N,N-TMT • 4-HO-5-MeO-DMT • 4-Acetoxy-DET • 4-Acetoxy-DIPT • 4-Acetoxy-DMT • 4-Acetoxy-DPT • 4-Acetoxy-MiPT • 4-HO-DPT • 4-HO-MET • 4-Propionyloxy-DMT • 4-Hydroxy-N-Methyl-(α,N-trimethylene)tryptamine • 5-Me-MIPT • 5-N,N-TMT • 5-AcO-DMT • 5-MeO-2,N,N-TMT • 5-MeO-4,N,N-TMT • 5-MeO-α,N,N-TMT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DALT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DIPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MeO-EiPT • 5-MeO-MET • 5-MeO-MIPT • 5-Methoxy-N-methyl-(α,N-trimethylene)tryptamine • 7,N,N-TMT • α,N,N-TMT • α-ET • α-MT • AL-37350A • Baeocystin • Bufotenin • DALT • DBT • DET • DIPT • DMT • DPT • EiPT • Ethocin • Ethocybin • Iprocin • MET • Miprocin • MIPT • Norbaeocystin • PiPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin;

Others: AL-38022A • Ibogaine • Noribogaine • Voacangine

|

|

Dissociatives

NMDAR antagonists |

Adamantanes: Amantadine • Memantine • Rimantadine;

Arylcyclohexylamines: 3-MeO-PCP • 4-MeO-PCP • Dieticyclidine • Esketamine • Eticyclidine • Gacyclidine • Ketamine • Methoxetamine • Neramexane • Phencyclidine • PCPr • Rolicyclidine • Tenocyclidine • Tiletamine;

Morphinans: Dextrallorphan • Dextromethorphan • Dextrorphan • Methorphan (Racemethorphan) • Morphan (Racemorphan);

Others: 2-MDP • 8A-PDHQ • Aptiganel • Dexoxadrol • Dizocilpine (MK-801) • Etoxadrol • Ibogaine • Midafotel • NEFA • Nitrous Oxide • Noribogaine • Perzinfotel • Remacemide • Selfotel • Xenon

|

|

Deliriants

mAChR antagonists |

3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate • Atropine • Benactyzine • Benzatropine • Benzydamine • Biperiden • Brompheniramine • CAR-226,086 • CAR-301,060 • CAR-302,196 • CAR-302,282 • CAR-302,368 • CAR-302,537 • CAR-302,668 • Chlorpheniramine • Chloropyramine • Clemastine • CS-27349 • Cyclizine • Cyproheptadine • Dicyclomine (Dicycloverine) • Dimenhydrinate • Diphenhydramine • Ditran • Doxylamine • EA-3167 • EA-3443 • EA-3580 • EA-3834 • Elemicin • Flavoxate • Hydroxyzine • Hyoscyamine • Meclizine • Myristicin • N-Ethyl-3-piperidyl benzilate • N-Methyl-3-piperidyl benzilate • Pyrilamine • Orphenadrine • Oxybutynin • Pheniramine • Phenyltoloxamine • Procyclidine • Promethazine • Scopolamine (Hyoscine) • Tolterodine • Trihexyphenidyl • Tripelennamine • Triprolidine • WIN-2299

|

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

Cannabinol • CP-47,497 • CP-55,244 • CP-55,940 • DMHP • HU-210 • JWH-018 • JWH-030 • JWH-073 • JWH-081 • JWH-200 • JWH-250 • Nabilone • Nabitan • Nantradol • Parahexyl • THC (Dronabinol) • WIN-55,212-2

|

|

|

D2R agonists

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2-EMSB • 2-MMSB • Alazocine • Bremazocine • Butorphanol • Cyclazocine • Cyprenorphine • Dextrallorphan • Dezocine • Enadoline • Herkinorin • HZ-2 • Ibogaine • Ketazocine • Metazocine • Nalbuphine • Nalorphine • Noribogaine • Pentazocine • Phenazocine • Salvinorin A • Spiradoline • Tifluadom • U-50,488 • U-69,593

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Efavirenz • Glaucine • Isoaminile

|

|

|

|

Serotonergics |

|

|

5-HT1 receptor ligands |

|

|

5-HT1A

|

Agonists: Azapirones: Alnespirone • Binospirone • Buspirone • Enilospirone • Eptapirone • Gepirone • Ipsapirone • Perospirone • Revospirone • Tandospirone • Tiospirone • Umespirone • Zalospirone; Antidepressants: Etoperidone • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Quetiapine • Ziprasidone; Ergolines: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • Methysergide • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • DMT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • Adatanserin • Befiradol • BMY-14802 • Cannabidiol • Dimemebfe • Ebalzotan • Eltoprazine • F-11,461 • F-12,826 • F-13,714 • F-14,679 • F-15,063 • F-15,599 • Flesinoxan • Flibanserin • Lesopitron • Lu AA21004 • LY-293,284 • LY-301,317 • MKC-242 • NBUMP • Osemozotan • Oxaflozane • Pardoprunox • Piclozotan • Rauwolscine • Repinotan • Roxindole • RU-24,969 • S 14,506 • S-14,671 • S-15,535 • Sarizotan • SSR-181,507 • Sunepitron • U-92016A • Urapidil • Vilazodone • Xaliproden • Yohimbine

Antagonists: Antipsychotics: Iloperidone • Risperidone • Sertindole; Beta blockers: Alprenolol • Cyanopindolol • Iodocyanopindolol • Oxprenolol • Pindobind • Pindolol • Propranolol • Tertatolol; Others: AV965 • BMY-7378 • CSP-2503 • Dotarizine • Flopropione • GR-46611 • Isamoltane • Lecozotan • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MPPF • NAN-190 • PRX-00023 • Robalzotan • S-15535 • SB-649915 • SDZ 216-525 • Spiperone • Spiramide • Spiroxatrine • UH-301 • WAY-100,135 • WAY-100,635 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

5-HT1B

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Methysergide; Piperazines: Eltoprazine • TFMPP; Triptans: Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CGS-12066A • CP-93,129 • CP-94,253 • CP-135,807 • RU-24969

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: AR-A000002 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Isamoltane • Metitepine/Methiothepin • SB-216,641 • SB-224,289 • SB-236,057 • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT1D

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Methysergide; Triptans: Almotriptan • Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Frovatriptan • Naratriptan • Rizatriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CP-135,807 • CP-286,601 • GR-46611 • L-694,247 • L-772,405 • PNU-109,291 • PNU-142,633

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: Alniditan • BRL-15572 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Ketanserin • LY-310,762 • LY-367,642 • LY-456,219 • LY-456,220 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • Yohimbine • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

5-HT1E

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Methysergide; Triptans: Eletriptan; Tryptamines: BRL-54443 • Tryptamine

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

5-HT1F

|

Agonists: Triptans: Eletriptan • Naratriptan • Sumatriptan; Tryptamines: 5-MT; Others: BRL-54443 • Lasmiditan • LY-334,370

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT2 receptor ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT2A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: ALD-52 • Ergonovine • Lisuride • LA-SS-Az • LSD • LSD-Pip • Lysergic acid 2-butyl amide • Methysergide; Phenethylamines: 25I-NBMD • 25I-NBOH • 25I-NBOMe • 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2CB-Ind • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • 2CBCB-NBOMe • 2CBFly-NBOMe • Bromo-DragonFLY • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline • TCB-2 • TFMFly; Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: AL-34662 • AL-37350A • Dimemebfe • Medifoxamine • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • RH-34

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Amperozide • Aripiprazole • Carpipramine • Clocapramine • Clozapine • Gevotroline • Iloperidone • Melperone • Mosapramine • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Others: 5-I-R91150 • AC-90179 • Adatanserin • Altanserin • AMDA • APD-215 • Blonanserin • Cinanserin • CSP-2503 • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eplivanserin • Esmirtazapine • Fananserin • Flibanserin • Ketanserin • KML-010 • Lubazodone • Mepiprazole • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Nantenine • Pimavanserin • Pizotifen • Pruvanserin • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • S-14,671 • Sarpogrelate • Setoperone • Spiperone • Spiramide • SR-46349B • Volinanserin • Xylamidine • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2B

|

Agonists: Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex; Phenethylamines: Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • Fenfluramine • MDA • MDMA • Norfenfluramine; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • α-Methyl-5-HT; Others: BW-723C86 • Cabergoline • mCPP • Pergolide • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175

Antagonists: Agomelatine • Asenapine • EGIS-7625 • Ketanserin • Lisuride • LY-272,015 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • PRX-08066 • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • RS-127,445 • Sarpogrelate • SB-200,646 • SB-204,741 • SB-206,553 • SB-215,505 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SDZ SER-082 • Tegaserod • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2C

|

Agonists: Phenethylamines: 2C-B • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline; Piperazines: Aripiprazole • mCPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: A-372,159 • AL-38022A • CP-809,101 • Dimemebfe • Lorcaserin• Medifoxamine • MK-212 • ORG-37,684 • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175 • Vabicaserin • WAY-629 • WAY-161,503 • YM-348

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Iloperidone • Melperone • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Agomelatine • Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Fluoxetine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Nortriptyline • Trazodone; Others: Adatanserin • Cinanserin • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eltoprazine • Esmirtazapine • FR-260,010 • Ketanserin • Ketotifen • Latrepirdine • Lu AA24530 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Methysergide • Pizotifen • Ritanserin • RS-102,221 • S-14,671 • SB-200,646 • SB-206,553 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SB-242,084 • SB-243,213 • SDZ SER-082 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT3

|

Agonists: Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-CT; Others: Chlorophenylbiguanide • Butanol • Ethanol • Halothane • Isoflurane • RS-56812 • SR-57,227 • SR-57,227-A • Toluene • Trichloroethane • Trichloroethanol • Trichloroethylene • YM-31636

Antagonists: Antiemetics: AS-8112 • Alosetron • Azasetron • Batanopride • Bemesetron • Cilansetron • Dazopride • Dolasetron • Granisetron • Lerisetron • Ondansetron • Palonosetron • Ramosetron • Renzapride • Tropisetron • Zacopride • Zatosetron; Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Olanzapine • Quetiapine; Tetracyclic antidepressants: Amoxapine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine; Others: CSP-2503 • ICS-205,930 • Lu AA21004 • Lu AA24530 • MDL-72,222 • Memantine • Nitrous Oxide • Ricasetron • Sevoflurane • Thujone • Xenon

|

|

|

5-HT4

|

Agonists: Gastroprokinetic Agents: Cinitapride • Cisapride • Dazopride • Metoclopramide • Mosapride • Prucalopride • Renzapride • Tegaserod • Zacopride; Others: 5-MT • BIMU-8 • CJ-033,466 • PRX-03140 • RS-67333 • RS-67506 • SL65.0155 • TD-5108

Antagonists: GR-113,808 • GR-125,487 • L-Lysine • Piboserod • RS-39604 • RS-67532 • SB-203,186

|

|

|

5-HT5A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Ergotamine • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT; Others: Valerenic Acid

Antagonists: Asenapine • Latrepirdine • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • SB-699,551

* Note that the 5-HT5B receptor is not functional in humans.

|

|

|

5-HT6

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • LSD • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-BT • 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • E-6801 • E-6837 • EMD-386,088 • EMDT • LY-586,713 • N-Methyl-5-HT • Tryptamine; Others: WAY-181,187 • WAY-208,466

Antagonists: Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Doxepin • Mianserin • Nortriptyline; Atypical antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Fluperlapine • Iloperidone • Olanzapine • Tiospirone; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: BGC20-760 • BVT-5182 • BVT-74316 • EGIS-12233 • GW-742,457 • Ketanserin • Latrepirdine • Lu AE58054 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MS-245 • PRX-07034 • Ritanserin • Ro 04-6790 • Ro 63-0563 • SB-258,585 • SB-271,046 • SB-357,134 • SB-399,885 • SB-742,457

|

|

|

5-HT7

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • AS-19 • Bifeprunox • LP-12 • LP-44 • RU-24,969 • Sarizotan

Antagonists: Lysergamides: 2-Bromo-LSD • Bromocriptine • Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Imipramine • Maprotiline • Mianserin; Atypical antipsychotics: Amisulpride • Aripiprazole • Clozapine • Olanzapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Tiospirone • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: Butaclamol • EGIS-12233 • Ketanserin • LY-215,840 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Pimozide • Ritanserin • SB-258,719 • SB-258,741 • SB-269,970 • SB-656,104 • SB-656,104-A • SB-691,673 • SLV-313 • SLV-314 • Spiperone • SSR-181,507

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

SERT

|

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Alaproclate • Citalopram • Dapoxetine • Desmethylcitalopram • Desmethylsertraline • Escitalopram • Femoxetine • Fluoxetine • Fluvoxamine • Indalpine • Ifoxetine • Litoxetine • Lu AA21004 • Lubazodone • Panuramine • Paroxetine • Pirandamine • RTI-353 • Seproxetine • Sertraline • Vilazodone • Zimelidine; Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Bicifadine • Desvenlafaxine • Duloxetine • Eclanamine • Levomilnacipran • Milnacipran • Sibutramine • Venlafaxine; Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (SNDRIs): Brasofensine • Diclofensine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • NS-2359 • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Tesofensine; Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): Amitriptyline • Butriptyline • Cianopramine • Clomipramine • Desipramine • Dosulepin • Doxepin • Imipramine • Lofepramine • Nortriptyline • Pipofezine • Protriptyline • Trimipramine; Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs): Amoxapine; Piperazines: Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antihistamines: Brompheniramine • Chlorpheniramine • Diphenhydramine • Mepyramine/Pyrilamine • Pheniramine • Tripelennamine; Opioids: Meperidine (Pethidine) • Methadone • Propoxyphene; Others: Cocaine • CP-39,332 • Cyclobenzaprine • Dextromethorphan • Dextrorphan • EXP-561 • Fezolamine • Mesembrine • Nefopam • PIM-35 • Pridefrine • Roxindole • SB-649,915 • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

VMAT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Aminoindanes: 5-IAI • ETAI • MDAI • MDMAI • MMAI • TAI; Aminotetralins: 6-CAT • 8-OH-DPAT • MDAT • MDMAT; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex • Clominorex • Fluminorex; Phenethylamines (also Amphetamines, Cathinones, Phentermines, etc): 2-Methyl-MDA • 4-CAB • 4-FA • 4-FMA • 4-HA • 4-MTA • 5-APDB • 5-Methyl-MDA • 6-APDB • 6-Methyl-MDA • Amiflamine • BDB • BOH • Brephedrone • Butylone • Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • Diethylcathinone • Dimethylcathinone • DMA • DMMA • EBDB • EDMA • Ethylone • Etolorex • Fenfluramine (Dexfenfluramine) • Flephedrone • IAP • IMP • Lophophine • MBDB • MDA • MDEA • MDHMA • MDMA • MDMPEA • MDOH • MDPEA • Mephedrone • Methedrone • Methylone • MMA • MMDA • MMDMA • NAP • Norfenfluramine • pBA • pCA • pIA • PMA • PMEA • PMMA • TAP; Piperazines: 2C-B-BZP • BZP • MBZP • mCPP • MDBZP • MeOPP • Mepiprazole • pFPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 4-Methyl-αET • 4-Methyl-αMT • 5-CT • 5-MeO-αET • 5-MeO-αMT • 5-MT • αET • αMT • DMT • Tryptamine (itself); Others: Indeloxazine • Tramadol • Viqualine

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

TPH

|

AGN-2979 • Fenclonine

|

|

|

AAAD

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

|

|

|

MAO

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A Selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity enhancers: BPAP • PPAP; Reuptake enhancers: Tianeptine

|

|

|

|

|

Phenethylamines |

|

| Phenethylamines |

Psychedelics: 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2C-C • 2C-D • 2C-E • 2C-F • 2C-G • 2C-I • 2C-N • 2C-P • 2C-SE • 2C-T • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-4 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-8 • 2C-T-9 • 2C-T-13 • 2C-T-15 • 2C-T-17 • 2C-T-21 • 2C-TFM • 2C-YN • Allylescaline • DESOXY • Escaline • Isoproscaline • Jimscaline • Macromerine • MEPEA • Mescaline • Metaescaline • Methallylescaline • Proscaline • Psi-2C-T-4 • TCB-2

Stimulants: 2-OH-PEA • β-Me-PEA • Hordenine • N-Me-PEA • Phenethylamine (PEA)

Entactogens: Lophophine • MDPEA • MDMPEA

Others: BOH • DMPEA

|

|

Amphetamines

Phenylisopropylamines |

Psychedelics: 3C-BZ • 3C-E • 3C-P • Aleph • Beatrice • Bromo-DragonFLY • D-Deprenyl • DMA • DMCPA • DMMDA • DOB • DOC • DOEF • DOET • DOI • DOM • DON • DOPR • DOTFM • Ganesha • MMDA • MMDA-2 • Psi-DOM • TMA • TeMA

Stimulants: 4-MA • 4-MMA • 4-MTA • 5-IT • Alfetamine • Amfecloral • Amfepentorex • Amphetamine ( Dextroamphetamine, Levoamphetamine) • Amphetaminil • Benfluorex • Benzphetamine • Cathine • Clobenzorex • Dimethylamphetamine • Ephedrine (EPH) • Ethylamphetamine • Fencamfamine • Fencamine • Fenethylline • Fenfluramine (Dexfenfluramine) • Fenproporex • Fludorex • Furfenorex • Isopropylamphetamine • Lefetamine • Mefenorex • Methamphetamine ( Dextromethamphetamine, Levomethamphetamine) • Methoxyphenamine • MMA • Oxilofrine • Ortetamine • PBA • PCA • Phenpromethamine • PFA • PFMA • PIA • PMA • PMEA • PMMA • Phenylpropanolamine (PPA) • Prenylamine • Propylamphetamine • Pseudoephedrine (PSE) • Sibutramine • Tiflorex (Flutiorex) • Tranylcypromine • Xylopropamine • Zylofuramine

Entactogens: 5-APDB • 6-APB • 6-APDB • IAP • MDA • MDEA • MDHMA (FLEA) • MDMA ("Ecstasy") • MDOH • MMDMA • NAP • TAP

Others: Amiflamine • D-Deprenyl • L-Deprenyl (Selegiline)

|

|

| Phentermines |

Stimulants: Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • Clortermine • Etolorex • Mephentermine • Pentorex (Phenpentermine) • Phentermine

Entactogens: MDPH • MDMPH

|

|

| Cathinones |

Stimulants: Amfepramone • Brephedrone • Buphedrone • Bupropion (Amfebutamone) • Cathinone (Propion) • Dimethylcathinone (Dimethylpropion, Metamfepramone) • Ethcathinone (Ethylpropion) • Flephedrone • Methcathinone (Methylpropion) • Mephedrone • Methedrone

Entactogens: Ethylone • Methylone

|

|

| Phenylisobutylamines |

Entactogens: 4-CAB • 4-MAB • Ariadne (α-Et-DOM) • BDB (J) • Butylone (bk-MBDB) • EBDB (Ethyl-J) • Eutylone (bk-EBDB) • MBDB (Methyl-J)

Stimulants: Phenylisobutylamine

|

|

| Phenylalkylpyrrolidines |

Stimulants: α-PBP • α-PPP • α-PVP • MDPBP • MDPPP • MDPV • MOPPP • MPBP • MPHP • MPPP • Naphyrone • PEP • Prolintane • Pyrovalerone

|

|

Catecholamines

(and relatives..) |

6-FNE • 6-OHDA • α-Me-DA • α-Me-TRA • Adrenochrome • Ciladopa • D-DOPA (Dextrodopa) • Dopamine • Epinephrine (Adrenaline) • Epinine • Fenclonine • Ibopamine • L-DOPA (Levodopa) • L-DOPS (Droxidopa) • L-Phenylalanine • L-Tyrosine • meta-Octopamine • meta-Tyramine • Metanephrine • Metirosine • Methyldopa • Nordefrin (Levonordefrin) • Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline) • Normetanephrine • para-Octopamine • para-Tyramine |

|

| Miscellaneous |

Amidephrine • Arbutamine • Cafedrine • Denopamine • Dobutamine • Dopexamine • Etafedrine • Ethylnorepinephrine • Etilefrine • Famprofazone • Gepefrine • Isoprenaline (Isoproterenol) • Isoetarine • Metaraminol • Metaterol • Methoxamine • Norfenefrine • Orciprenaline • Phenylephrine (Neosynephrine) • Phenoxybenzamine • Prenalterol • Pronethalol • Propranolol • Salbutamol (Albuterol; Levosalbutamol) • Synephrine (Oxedrine) • Theodrenaline • Xamoterol |

|

|

Drugs from PiHKAL |

|

AEM · AL · Aleph · Aleph-2 · Aleph-4 · Aleph-6 · Aleph-7 · Ariadne · Asymbescaline · Buscaline · Beatrice · Bis-TOM · BOB · BOD · BOH · BOHD · BOM · 4-Bromo-3,5-dimethoxyamphetamine · 2-Bromo-4,5-methylenedioxyamphetamine · 2C-B · 3C-BZ · 2C-C · 2C-D · 2C-E · 3C-E · 2C-F · 2C-G · 2C-G-3 · 2C-G-4 · 2C-G-5 · 2C-G-N · 2C-H · 2C-I · 2C-N · 2C-O · 2C-O-4 · 2C-P · CPM · 2C-SE · 2C-T · 2C-T-2 · 2C-T-4 · psi-2C-T-4 · 2C-T-7 · 2C-T-8 · 2C-T-9 · 2C-T-13 · 2C-T-15 · 2C-T-17 · 2C-T-21 · 4-D · beta-D · DESOXY · 2,4-DMA · 2,5-DMA · 3,4-DMA · DMCPA · DME · DMMDA · DMMDA-2 · DMPEA · DOAM · DOB · DOBU · DOC · DOEF · DOET · DOI · DOM · psi-DOM · DON · DOPR · Escaline · EEE · EEM · EME · EMM · Ethyl-J (EBDB) · Ethyl-K · F-2 · F-22 · Flea · G-3 · G-4 · G-5 · G-N · Ganesha · HOT-2 · HOT-7 · HOT-17 · IDNNA · Isomescaline · Isoproscaline · Iris · J (BDB) · Lophophine · PMA · Mescaline · Madam-6 · Methallylescaline · MDA · MDAL · MDBU · MDBZ · MDCPM · MDDM · MDE · MDHOET · MDIP · MDMA · MDMC (EDMA) · MDMEO · MDMEOET · MDMP · MDOH · MDPEA · MDPH · MDPL · MDPR · Metaescaline · MEDA · MEE · MEM · MEPEA · Meta-DOB · Meta-DOT · Methyl-DMA · Methyl-DOB · Methyl-J (MBDB) · Methyl-K · Methyl-MA (PMMA) · Methyl-MMDA-2 · MMDA · MMDA-2 · MMDA-3a · MMDA-3b · MME · Metaproscaline · MPM · Ortho-DOT · Proscaline · Phenescaline · Phenethylamine · Propynyl · Symbescaline · 2,3,4,5-Tetramethoxyamphetamine · 3-TASB · 4-TASB · 5-TASB · Thiobuscaline · 3-TE · 4-TE · 3-TIM · 4-TIM · 5-TIM · 3-TM · 4-TM · TMA · TMA-2 · TMA-3 · TMA-4 · TMA-5 · TMA-6 · 3-TME · 4-TME · 5-TME · 2T-MMDA-3a · 4T-MMDA-2 · 2-TOET · 5-TOET · 2-TOM · 5-TOM · TOMSO · Thioproscaline · Trisescaline · 3-TSB · 4-TSB · 3-T-Trisescaline · 4-T-Trisescaline

|

|