Einsteinium

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| silver-colored | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name, symbol, number | einsteinium, Es, 99 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pronunciation | /aɪnˈstaɪniəm/ eyen-STYE-nee-əm |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | actinide | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, period, block | n/a, 7, f | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight | (252)g·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f11 7s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 29, 8, 2 (Image) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.84 g·cm−3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1133 K, 860 °C, 1580 °F | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 2, 3, 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | 1.3 (Pauling scale) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | 1st: 619 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellanea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS registry number | 7429-92-7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most stable isotopes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main article: Isotopes of einsteinium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Einsteinium (pronounced /aɪnˈstaɪniəm/, eyen-STYE-nee-əm) is a metallic synthetic element. On the periodic table, it is represented by the symbol Es and atomic number 99. It is the seventh transuranic element, and an actinide. It was named in honor of Albert Einstein.[1]

Its position on the periodic table indicates that its chemical and physical properties are similar to other metals. Though only small amounts have been made, it has been determined to be silver-colored.[1] According to tracer studies conducted at Los Alamos National Laboratory using the isotope 253Es, this element has chemical properties typical of a heavy trivalent, actinide element.[2]

Like all synthetic elements, isotopes of einsteinium are extremely radioactive and are considered highly toxic.

Contents |

Production

Einsteinium does not occur naturally in any measurable quantities. The modern process of creating the element starts with the irradiation of plutonium-239 in a nuclear reactor for several years. The resulting plutonium-242 isotope (in the form of the compound plutonium(IV) oxide) is mixed with aluminium and formed into pellets. The pellets are then further irradiated for approximately one year in a nuclear reactor. Another four months of irradiation is required in a different reactor. The result is a mixture of californium and einsteinium, which can then be separated.[2]

Uses

Aside from basic scientific research (such as being a step in the production of other elements[3]), einsteinium has no known uses.[4]

Isotopes

Nineteen radioisotopes of einsteinium have been characterized,[5] with the most stable being 252Es with a half-life of 471.7 days. 254Es has a half-life of 275.7 days, 255Es 39.8 days and 253Es 20.47 days. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 40 hours, the majority of these having half-lives that are less than 30 minutes. This element also has three meta states, with the most stable being 254mEs (t½ = 39.3 hours). The isotopes of einsteinium range in atomic mass from 240.069 u (240Es) to 258.100 u (258Es).

Known compounds

The following is a list of known compounds of einsteinium:[6]

- EsBr3 einsteinium(III) bromide

- EsCl2 einsteinium(II) chloride

- EsCl3 einsteinium(III) chloride

- EsF3 einsteinium(III) fluoride

- EsI2 einsteinium(II) iodide

- EsI3 einsteinium(III) iodide

- Es2O3 einsteinium(III) oxide

History

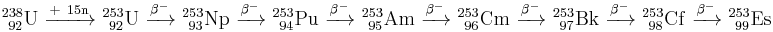

Einsteinium was first identified in December 1952 by Albert Ghiorso and co-workers at the University of California at Berkeley.[2] They were examining debris from the first hydrogen bomb test, which took place on November 1, 1952 (see the Ivy Mike H-bomb test]]).[1][7] They discovered the isotope 253Es (half-life 20.5 days) that was made by the capture of 15 neutrons by uranium-238 nuclei – which then underwent seven successive beta decays).

These findings were kept secret until 1955 due to Cold War tensions.[8][9] Some 238U atoms, however, could capture another amount of neutrons (most likely, 16 or 17):

Isotopes of einsteinium were produced shortly afterward at the University of California Radiation Laboratory in a nuclear reaction between nitrogen-14 and uranium-238 nuclei.[10] and later by intense neutron irradiation of plutonium in the Materials Testing Reactor.[11]

In 1961, enough einsteinium was synthesized to prepare a microscopic amount of 253Es. This sample weighed about 10 micrograms, and it was weighed using a special balance. The material produced was used to produce mendelevium, element 101, by further nuclear reactions. More microscopic amounts of einsteinium have been produced at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory's High Flux Isotope Reactor in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, by bombarding plutonium-239 with neutrons. About three milligrams were created during a four-year program of irradiation and then chemical separation from a starting sample of one kg of plutonium.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Einsteinium – National Research Council Canada. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Einsteinium – Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ See Mendelevium#History

- ↑ It's Elemental – The Element Einsteinium. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ Table of Isotopes decay data – LBNL Isotopes Project – LUNDS Universitet. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ↑ Chemistry : Periodic Table : einsteinium : compounds information – WebElements. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ↑ Albert Ghiorso (2003). "Einsteinium and Fermium". Chemical and Engineering News. http://pubs.acs.org/cen/80th/einsteiniumfermium.html.

- ↑ Ghiorso, A. and Thompson, S. G. and Higgins, G. H. and Seaborg, G. T. and Studier, M. H. and Fields, P. R. and Fried, S. M. and Diamond, H. and Mech, J. F. and Pyle, G. L. and Huizenga, J. R. and Hirsch, A. and Manning, W. M. and Browne, C. I. and Smith, H. L. and Spence, R. W. (1955). "New Elements Einsteinium and Fermium, Atomic Numbers 99 and 100". Phys. Rev. 99: 1048–1049. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.99.1048.

- ↑ P. R. Fields, M. H. Studier, H. Diamond, J. F. Mech, M. G. Inghram, G. L. Pyle, C. M. Stevens, S. Fried, W. M. Manning (Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, Illinois); A. Ghiorso, S. G. Thompson, G. H. Higgins, G. T. Seaborg (University of California, Berkeley, California): "Transplutonium Elements in Thermonuclear Test Debris", in: Physical Review 1956, 102 (1), 180–182; doi:10.1103/PhysRev.102.180.

- ↑ Ghiorso, Albert and Rossi, G. Bernard and Harvey, Bernard G. and Thompson, Stanley G. (1954). "Reactions of U-238 with Cyclotron-Produced Nitrogen Ions". Physical Review 93: 257. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.93.257.

- ↑ Thompson, S. G. and Ghiorso, A. and Harvey, B. G. and Choppin, G. R. (1954). "Transcurium Isotopes Produced in the Neutron Irradiation of Plutonium". Physical Review 93: 908. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.93.908.

Literature

- Stwertka, Albert (1996). A Guide to the Elements. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195080831.

External links

- It's Elemental - The Element Einsteinium

- WebElements.com - Einsteinium

- Albert Ghiorso about the discovery

| H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | ||||||||||

| Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Uut | Uuq | Uup | Uuh | Uus | Uuo | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\mathrm{^{238}_{\ 92}U\ \xrightarrow [-7\ \beta^-]{+\ 15,\ 16,\ 17\ (n,\gamma)} \ ^{253,\ 254,\ 255}_{\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ 99}Es}](/I/9f1fefa0969b5f393d87a46fdb1a5859.png)